My Time in Calormen

Most readers of Speculative Faith will immediately recognize “Calomen” as the fictional land portrayed by C.S. Lewis in the Chronicles of Narnia. A desert land south of both Archenland and Narnia, with exaggerated Middle Eastern customs, polytheism that has the vicious god Tash at the head of its pantheon, rigid social classes, strong divisions between genders, and slavery (here, if you aren’t familiar, the linked Wikipedia article summarizes it pretty well). At the time Lewis wrote it, some elements of the descriptions of Calormen clearly seemed intended to be humorous–but people of modern times are mostly not amused. It’s now broadly and routinely claimed that C.S. Lewis grew up in an overtly racist era and he was overtly racist himself. That his racism shines forth in his criticisms of the brown people of Calormen–and perhaps in some other ways as well, such as by portraying dark-skinned dwarfs (like Nikabrik) worse than lighter-skinned dwarfs (like Trumpkin).

I have of course never been to Calomen–how could I have been? It’s a fictional place. Where I have been instead (in order of my time there) is the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Qatar, Afghanistan, Bahrain, and Djibouti. These countries have many differences among them–they aren’t even in the same region, because Djibouti is part of the Horn of Africa and Afghanistan is in Central Asia and the rest are in the “Middle East” (or “Near East,” some people say). But one thing they all share in common is all of these nations are Islamic-majority nations. And I’m going to assert in this article that they really do have some things in common with fictional Calormen, drawing especially from my first experience in the UAE.

I’m here to tell my own story, but as I tell it, bear in mind my experiences point in a certain direction. Perhaps Lewis can rightly be accused of preferring Europe over the Middle East without really understanding it–which would be ethnocentrism and not racism per se. Or perhaps there were elements of actual racism in his thinking–I don’t know, because I can’t say for sure I know what he was thinking (certainly he had no trouble portraying pale-skinned villains, re: the White Witch). And certainly by modern standards some of his jokes may seem unfunny, like “may he live forever” called out every time the Tisroc is mentioned. But I wish to point out that included within all of that potentially negative motivation from Lewis comes some legitimate criticism of Islamic culture and deliberate contrasts with it and the aristocracy that Lewis believed in and praised in his portrayals of Narnia and Archenland.

The Tisroc, may he live forever!

So in 1989 I enlisted in the US Army Reserve (USAR). There’s a backstory of why I did that which includes the death of premature twin boys that put my wife (now ex-wife) and I into debt and me seeking college money, money provided by the Reserve GI Bill of the period. Now isn’t the time to tell that other story in full, but my enlistment in the USAR was in an entirely different context in 1989 than what it became.

In 1989, Reservists hadn’t been called up in significant numbers since WWII and none at all since the Vietnam War. When I went through Army Basic Training and medical training in the Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) I chose–“Cardiac Specialist,” which at the time was a glorified EKG tech with some elements of Army combat medicine thrown in–my expectation was to put in eight years in the Reserves, then boom, I’d be done. If there was going to be a war, all the talk among Reservists at the time was if World War III happened we’d be pressed into service. I was in the 5502nd US Army Hospital in Aurora, Colorado when my training was complete and we always talked about getting “called up” if nuclear weapons fell on the USA and Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in Aurora were somehow still standing, then we’d be helping take care of massive casualties. A nightmare scenario that nobody could really plan for and we didn’t even seriously try, though we did get practice phone calls for mobilization to see if we’d reply to the calls on short notice.

But then on the 2nd of August, 1990 (just 7 months after I finished my Cardiac Specialist training), the dictator of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, decided to send his military into the neighboring oil-rich country of Kuwait. Saudi Arabia, who at the time had a minuscule, poorly-trained military, got very nervous that Iraq could roll right through and conquer them as well. And militarily, they could have. In fact, at the time, the Iraqis probably had the military capacity to conquer the entire Arabian peninsula if they’d wanted. So the Saudis called for help–and the United Nations authorized an international response.

US troops started moving to Saudi Arabia as early as August, which steamrolled into a massive buildup of US troops and troops from other nations. Still, mostly whole units were being called and we were assured the nature of our unit was such that it most likely would not be activated. Deployment was not our mission (we had too many diverse medical specialties designed for stateside medical care).

So when on December 22nd, 1990 when I got a phone call at the security desk of the high-rise building in downtown Denver where I worked, the first thing the administrator from my unit told me was, “You’d better sit down.” I sat and he gave me news that I didn’t completely absorb until later–I was one of only 10 out of around 500 unit members who had been mobilized. I was the only person in my MOS from my unit with activation orders. Oh, you had a baby at home, born on December 18th, just four days previously? “Sorry.” You have orders to report in Bismark, North Dakota on the 27th of December at your new unit, the 311th Evacuation Hospital. In just five days.

And by the way, “Merry Christmas!”

I didn’t even know the Army could pull people from other units to fill missions at will back then. Now it’s something that happens all the time, but then it was so rare I’d never heard of it.

Of course it was forty below zero in Bismark when I arrived, but those details are not part of this story. Nor is the trudging around waist-deep snow at the WWII-era barracks at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin, part of this story either. Nor is Private First Class Perry shoveling coal into the stoves that kept us warm (before being made a driver) included in the tale. I’m not even going to give detail to the fact the unit went overseas but I had to go back to Denver, because I was a witness at a murder trial and had to testify (that’s a story for another time).

My unit was already in country when I flew in the back of a US Air Force C-141 Starlifter cargo plane from the United States to an air base outside of Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates. From the airbase, a truck took me and two other late additions to the unit to Mafraq Hospital, a hospital that the UAE government had built at a crossroads in an area ten kilometers from the city outskirts, in case of major emergencies and flooding along the coast (today a search for the old site on Google Maps shows the area is full of new buildings).

Unlike pretty much every other US Army medical unit that went to Saudi Arabia and a few other countries like the UAE, our military hospital unit was to share the same facility as a civilian hospital already in place. We were there in case of an overflow of US casualties (which never happened). We helped threat the regular civilian patients that would have come to that hospital anyway.

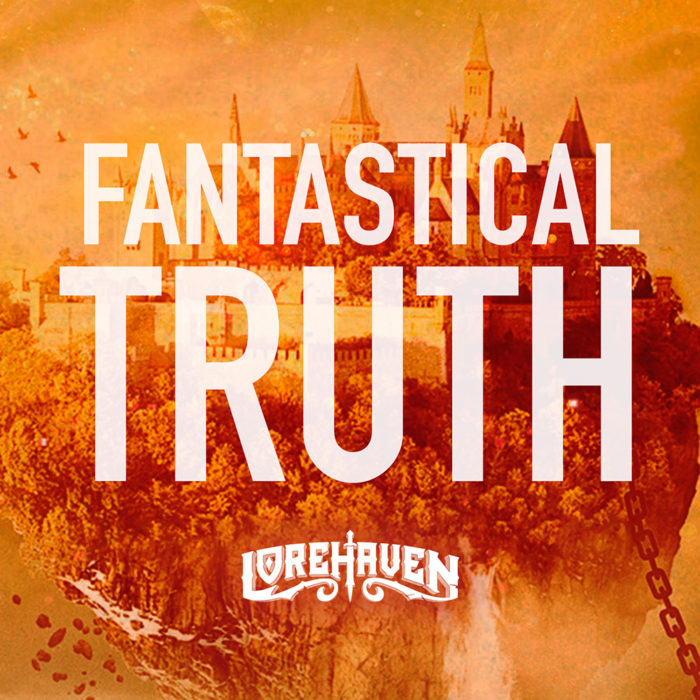

Our military hospital camped in tents by the hospital compound, though towards the end the UAE government provided us trailers. Because the UAE never expelled the Iraqi nationals who lived there, unlike Saudi Arabia, we were on full lock-down and couldn’t leave the compound and we in fact went to work in civilian clothing under the cover us of being “Red Crescent Volunteers” rather than US military. (Though we had to protect our compound with lower-ranking people like me pulling guard duty, wearing US military uniforms then and packing M16s–so I don’t think we were fooling anyone.)(One time I thought I would have to shoot someone while I was on guard duty, which was something I never believed I would have to do as a medic–but that’s not part of this story.)

Not my unit, but the same kind of tent and same uniforms from another USAR hospital during Desert Storm. Image source: Army Medical History

I wasn’t there quite three months before the unit got moved to Saudi Arabia in preparation for being sent back to the USA, but every day I worked with professionals at a hospital run to Middle Eastern standards, with Arab patients. Of course, most of the professionals were not from the UAE, only a very few were. The majority of the nurses were from the Philippines though many were Palestinian. Some were Arabs from other countries, mostly Egypt. Quite a few Pakistanis worked there, as did some Europeans, including Eastern Europeans (recall this was still during the Cold War, at the end, yes, but still). And poor guys from Bangladesh and India (especially Tamils) swept the floor and cleaned bathrooms.

I’d grown up in rural and small-town Montana. No exaggeration, I rode a horse to school in first and second grade and lived in a house that was half log cabin and had “outdoor plumbing” part of the time. But I’d also taken an interest in foreign language in high school and had been an exchange student to France for a summer. I spoke some French and Spanish and had studied New Testament Greek back in Montana and was just finishing my first semester of Hebrew at Colorado Christian University. So I wasn’t totally unfamiliar with foreign places and travel, but the Middle East was unlike anything I’d ever experienced before.

First, slavery. Outright slavery is illegal, but the countries on the Arabian side of the Gulf routinely bring workers from poor countries, house them in poor conditions, and work them hard. They send most of the money back home–this is not the same thing as slavery of course, they can’t be bought and sold and while they are sometimes physically abused, it isn’t as routine as what enslaved people faced in the history of US slavery. Still, they are pretty close to being slaves.

Plus, there’s the trade in brides. With the UAE being oil-rich and its citizens getting a stipend from oil sales (before you ask, becoming a UAE citizen is hard), lots of people who at that time had been poor just a generation previous suddenly had unexpected riches. Since Islam allows men who can financially support their wives to have four of them (like Jacob in the Bible did), many UAE men wanted to have four wives. But there weren’t enough native-born women in the UAE to allow that. So, where do they come from? Bride brokers that go to small, poor villages, mostly in Pakistan but also Muslim parts of India and other places. And pay parents and village elders for beautiful young women, where they are married off. That isn’t technically slavery, either, but it’s quite close.

Social divisions? Enormous. Sure, there are huge social divisions in certain places in the West as well, but there is a massive difference between the opulence for an Emir (basically a king) of an Emirate and being the Bangladeshi guy who sweeps the floor. Plus many steps in between (nurses from the Philippines seems to occupy their own rung). The difference in opulence, rights, privileges (including the top guys in UAE society totally ignoring the four-wife-limit and having as many women as they want) and power is massive. Such a difference does not exist to the same degree anywhere in North America or Europe.

If you are a Western woman living in the UAE or neighboring countries, life isn’t too bad. In fact, being a wife of a wealthy UAE guy is certainly luxurious. But there are some massive gender differences. Of course, pretty much everyone realizes that. It’s possible to overstate the differences between Middle Eastern society and ours and the difference is bigger in some places than others, but still. The difference is, in general, huge.

The hospital I worked in, for example, had male and female wards and separation of staff. Only a few male staff were allowed to go to female wards, though women could work on the male side.

Elaborate formality? Traditionally, yes, though those influenced by Western culture are not that way so much. But there are certain polite greetings commonly used and accepted for a wide variety of situations. Nothing I know of is as elaborately formal as Calormen as Lewis described it. Some aspects of Calormen sound like Herotodus’s description of the Persian Empire (Lewis was trained in classics like Herotodus) more than the modern Middle East. Still, there remain echoes of the ancient past in that part of the world. Some things are said almost as a ritual, including saying “inshalla” (if God wills) whenever talking about the future.

Religion is an interesting topic. Perhaps I will surprise you here.Â

As a young guy who eagerly studied foreign languages, I was anxious to try to learn Arabic. It was hard for me (Arabic is hard for Arabic speakers because it’s so diverse from country to country) but I picked up quite a few phrases. I talked to people. I asked questions. I was curious about them and their lives. And I talked to everyone. Even the Tamil guys (who often spoke English), who kept looking around worried, like they could get in trouble (eventually I figured that out and stopped talking to them).

I also was (and remain) something of a Christian zealot. My father drank heavily and was abusive at times (saying he was “alcoholic” would imply he was seeking treatment and at that time, he wasn’t), my mother was more abusive and when my parents divorced, that’s who I lived with (though she mellowed over time to a degree). I stopped going to church around age 11 and got immersed into the atheistic sub-culture of hard science fiction a-la Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein (while my older sister took the deep dive into fantasy that eventually led to her anti-Christian Pagan-friendliness) and loads of other lovely experiences–early exposure to pornography, plus other events like tragic accidents such as losing a finger in a woodcutting accident when I was seven and witnessing a gun accident in which a cousin shot my younger sister in the face when I was nine (my father was in charge when both these accidents took place). For me all of those experience I associated with “the world” and saw in Christ something better. The sin that drives the world I saw in sharp contrast with all that Christ can and will bring into the life of those who follow Him.

So for me, you might think I would have no patience with Islam. But what in fact happened is I saw a culture in which the idea of God really mattered, even if only in formality. A culture that eschews alcohol, which had caused so many problems in my family (though they do other drugs). A culture that prays publicly and formally from minarets with the Islamic call to prayer. In fact, I would often be up early, reading the Bible, when the first call to prayer would sound loud over the desert. My fellow soldiers would curse the noise it made, but I felt I had something in common with the person in the tower singing out in Arabic, “God is great.”

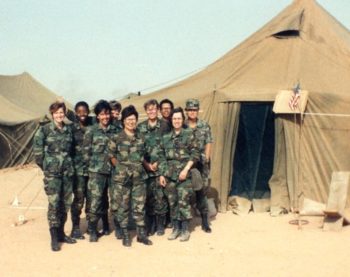

My positive impression of Islam was helped by one Dr. Namaan Baat (I’m not sure I’m spelling that right). He was a Pakistani cardiologist who worked I worked with frequently–oh, if you’re wondering why I was the only one in my MOS activated from my Reserve unit, it’s because this particular hospital had a cardiology department and they wanted a soldier who would be able to work there. (Plus I was in other ways more “deployable” than other people in my MOS–in good physical shape, good at my job). He and I had many discussions about Islam versus Christianity and I perceived him to be someone with genuine devotion to God and real love for people.

An Egyptian doctor whose face reminds me of Dr. Baat. Image source: pariscongress.com

Like Emeth, the one good guy from Calomen accepted into heaven according to C.S. Lewis in The Last Battle.

Note that I would not say I believe Dr. Baat is going to heaven. No, sometimes I wish it were not so, but the Gospel message in the New Testament is clear enough about the need for personal faith in Jesus the Messiah. But I would say he seemed to me to be sincerely interested in God and sincerely seeking to please Him. Unlike many of my fellow Americans, who mock and hate the very idea of the God of the Bible–people like Robert A. Heinlein.

So in spite of a recognition of genuine problems in the Islamic world, I walked away empathetic with it from my time in the UAE, with a sense that I as a devout Christian have more in common with Muslims than I do with Americans and other Westerners for whom faith has no meaning.

Though I’d return to the Middle East after that first trip. I entered Iraq on the exact same day, January 17th, that I’d flown into the UAE in 1991. Only seventeen years later. In Iraq, I met a few Muslims who seemed very sincere in their faith, but a lot who seemed to not care at all about it. There’s lots of whiskey-drinking going on in Iraq, which definitely left a negative personal impression on me, based on my own past. And that’s not all of course–there was lots of womanizing among some of the high-ranking Iraqi officers I worked with, loads and loads of that and other flavors of “ordinary” sin. Plus the “inshalla,” whose habitual use I’d appreciated, often was uttered not as a habit of acknowledging the importance of God’s will, but as a dodge to avoid making a commitment. (Though that’s not how they use it in Afghanistan.) Plus, I met Christian Iraqis afraid of persecution–a persecution that came upon many Christians as ISIS took over parts of the country after the US withdrawal from there in 2011.

The people you happen to run into randomly in life don’t qualify as a scientific sampling. But what you observe at least indicates some of what’s possible.

What I’ve seen is that the products of culture influenced by Christianity is in many ways better (of course, in my own evaluation of “better”) than what is found in Islamic culture. And I would say C.S. Lewis saw that, too. Probably not in the same way I did, but likely through things he’d read and perhaps via people he’d met.

I think there’s another possible element in Lewis’s focus on Calormen. That is, I think he may have received some criticism as being against individual liberty because he had warm feelings for royalty as in King Peter, King Edmund, Queen Susan, and Queen Lucy. By showing Calormen, it may be he meant to say, “Yes, I support the idea of royalty. But not the most vicious and authoritarian kind.”

So why did I write this? Not just because I thought talking about my past would make for a short, easy article (Ha! How wrong I was!). But because I also wanted to defend Lewis a bit, to say that criticism of a region of the world based on things they actually do isn’t the same as racism. In my case, while I may criticize “Calormen,” believe me, I have plenty of criticism for my own nation!

Parts of the Near East do have certain things in common with Calormen. Though it’s true Lewis exaggerated and got a bit silly (in part by trying to be funny) and used stereotypes. But thankfully Lewis did not show all Calormene people as cookie-cutter villains. He also showed Emeth.

So what are your thoughts on Calormen, readers? Do you have any pertinent personal experiences you’d like to share?

dabbled in all of them. I am certain that each one boasts some truly fine books. I am not saying that there is anything inherently inferior about such stories â let alone inherently wrong. Itâs simply that I â playing the odds of what I am most likely to enjoy â donât choose to read them anymore.

dabbled in all of them. I am certain that each one boasts some truly fine books. I am not saying that there is anything inherently inferior about such stories â let alone inherently wrong. Itâs simply that I â playing the odds of what I am most likely to enjoy â donât choose to read them anymore.

The truth about Neverland is

The truth about Neverland is The dancers of the Order direct their floating world

The dancers of the Order direct their floating world Enclave Escape is ready to launch with The Vault Between Spaces, by Chawna Schroeder, and we couldn’t be more excited! Take a peek behind the curtain of the first release with this exclusive seven-chapter sneak peek.

Enclave Escape is ready to launch with The Vault Between Spaces, by Chawna Schroeder, and we couldn’t be more excited! Take a peek behind the curtain of the first release with this exclusive seven-chapter sneak peek.

For details about your prize, Cathy, please contact me via Facebook messaging, either at my personal site or through the Spec Faith page. I also have a public Yahoo account that you can find at my

For details about your prize, Cathy, please contact me via Facebook messaging, either at my personal site or through the Spec Faith page. I also have a public Yahoo account that you can find at my