This post is more about the Christian faith than it is speculative, but works its way to talking about speculative fiction at the end. The title of this article may prove to be a bit misleading because I’m using the prefix “anti-” in one of its meanings in Greek, which means “as a substitute for” instead of how we usually use “anti-” in English, which is “against” or “opposite.” I’m linking an online New Testament Greek lexicon article on “áŒÎœÏ᜷“, which if you look at it you’ll see has two definitions. Definition 1, which includes “over against” and “opposite,” is the origin of the English meaning of something that’s opposite or against something–such as these examples from a linked online English dictionary: antiwar, anti-hero, and anti-bacterial. But the second definition’s got “for, instead of, in place of (something).” It’s that second definition I’m driving at here. So by “Anti-Faith” I mean a faith in something other than where Christianity places faith. Anti-hope is likewise hope in the wrong thing. And anti-love is a substitute for love. Not the real thing but not the complete opposite, either.

(A bit off topic, but if you didn’t know already, “Antichrist” has two possible meanings in NT Greek: One who opposes Christ/is the opposite of Christ OR one who is a substitute for Christ, which isn’t the same thing as being an opposite. Which of these definitions is correct? That depends on who you ask, but I think both are right. The Antichrist will be someone who sets himself up as the equivalent of Christ, substituting, but in fact will be in opposition to Christ…)

I’m going to focus on anti-love above the others I mentioned. Because just as Christians ought to be defined by our love for one another, as per John 13:35 and I Corinthians 13 and other passages (of course far too often we are not), the modern substitute for love defines our times in a powerful way. But let me get to the subject via a personal story:

Anti-Love on the Streets of New Orleans

I mentioned last week that I’d just returned from a mission trip to Mardi Gras with a ministry called No Greater Love (I’ll shorten that as “NGL”), which seeks to evangelize certain public events including Mardi Gras in New Orleans with an emphasis in talking about the love of Christ (though they do mention repentance as well). There were other evangelistic groups I saw on the streets of the French Quarter of New Orleans, some of which had signs that said things like “GOD HATES HOMOS” and “REPENT OR BURN IN HELL.” Representing a supposed Christian message, but one focusing on wrath. Let’s call those people, “No Greater Haters.”

“No Greater Haters” in New Orleans. Photo source: Advocate.com

What the “No Greater Haters” offer is in a sense anti-love but it’s not what I meant by coining the term. Though I must say people carrying angry signs and shouting at the crowd, focusing on the wrath of God, seem to me highly unlikely to prod anyone in the direction of personal salvation. Quite the opposite.

I mean, if I were Satan (the WWSD thing I mentioned a while ago), I’d definitely work on getting the angriest and most hateful people I could find to shout the gospel with an offensive snarl, in hopes of reducing the effectiveness of anyone talking about God’s love. A bit like how Soviet propaganda films looked for the worst examples of American society to show their citizens, focusing on things like abused homeless people and racism, to counteract stories of US wealth and easy living. Perhaps instead of my cynicism about the “No Greater Haters” I should see the situation the way the Apostle Paul did in that he rejoiced even when people preached Christ with evil motivations (Philippians 1:15-18)–but in fact, I wish the “No Greater Haters” were not there at all.

But instead of anti-love as hate, what I mean by “anti-love” was seen instead in something a woman on the street shouted at us as the NGL group marched by, our lead member carrying a wooden cross as we went. Note I carried the cross part of the way both on Monday (Lundi Gras) and Tuesday (Mardi Gras), because in addition to doing other things, our group marched both days. Some people shouted at us a variety of things, some obscene (such as vulgar references to what we should do with a p-word) and some members of the crowd threw things at our group, especially at the cross. Usually Mardi Gras beads, but I also got pegged with a nearly-full can of beer from a second floor balcony. (Taking the abuse without replying in kind we saw as us demonstrating in our bodies and actions how Jesus acted when put to the cross of Calvary.)

NGL on the way to or from Bourbon Street, away from the crowds. Note in 2020 our hats were gray, to prevent them looking like MAGA hats. Source: NGL Ministry’s Facebook page

So it when a woman shouted out to us, “Find somebody to love! Find somebody to love!” it was distinctive not that she was shouting, but what she was saying. And also how angry at us she seemed as she shouted it, but without using profanity. As if we were ones not representing love, but denying love.

I immediately perceived her angry criticism, but I didn’t know right away what it was about. I wondered if maybe she was trying to say that instead of marching the street, we should be helping homeless people or something (we actually did help a number of homeless people earlier in the day, but anyway). But when she switched to screeching, “Why do you hate love? Why do you hate love?” I understood what she was talking about.

She meant love as sex. Or more accurately, as erotic love (eros in Greek) which includes emotions along with sexuality. She saw us as marching because she thought we want to suppress sexuality. Which is not entirely true of course because we as a group did embrace married heterosexual “love” and we did not specifically single out sexual sins when we talked about the love of Christ. But it’s true our belief system did not embrace sexuality as the most important thing about a person and did include seeing sexual desire in certain contexts as wrong.

I don’t want to portray her as thinking deeper than she probably did, but there was absolutely no reason for her to use “love” as a euphemism for screwing. It’s not as if people were generally avoiding the use of profanity at that time and place.

I don’t think she meant it as a euphemism for the f-word, which we heard often enough on the streets. She meant what she shouted–for her, sex is love or else sex is so bound up with love that if a person is against sexuality to any degree, then that person ipso facto is against love: “Why are you against love?”

The woman represented a point of view I was already aware of in a way, but her shouting reinforced the idea of what she really meant. There’s nothing profound about me finally noticing, but for many people in today’s world, the meanings of “sex” and “love” are so linked together that sex has become a substitute for love.

Christian Love

Christian love can include many things, but is probably best defined by John 15:13, the key verse for the NGL ministry: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Love as self-sacrifice, love as self-denial, love even as suffering, the greatest example of which is the death of Jesus on the cross.

How well do Christians live self-sacrifice as love? Mostly not very well I would say. But that’s our ideal, one like the soldier who throws himself on a hand grenade to save his fellow soldiers or like the mother who throws herself at a wild animal attacking her children to save them.

Many, many Christians have seen sexual love as important, even though some, mostly in the historic past such as Augustine of Hippo, have felt that pleasures of the flesh even in marriage were not exactly good things. But even Christians who embrace sexuality rarely see sexual or marital love as the highest form of love. Our modern vision of love is different.

Anti-Love

That sex (more accurately eros) has risen in importance in the minds of modern people is evident from how important it is for many people to identify themselves by sexual preferences. Not just labels like gay or straight or even words like “pansexual,” but by “dominant” or “submissive” and many more labels. And people defend their rights to their full sexual expression.

Yes, sex has always been important, including of course at the time of the American Revolution. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson notoriously had many “love affairs.” But neither man fought for the right for their sexuality to be recognized and approved publicly. Yet rights to religious expression found a prominent place in their writings. So modern times represents a real change in attitudes towards what is more important, religion or sex.

That sex and love are intermingled in the minds of modern people is evident in some people having a hard time believing that David and Jonathan in the Bible were not lovers, because the Bible plainly says they loved each other. But love did not ever directly equal sex in Scriptures–genuine deep affection can happen without sex, as also seen in how some people see the disciple “whom Jesus loved.”

Sex of course does or should produce feelings of intimacy and closeness. It does link people together in a quasi-spiritual way (“the two shall become one flesh” of the Bible). It has aspects of pleasing someone else that are rather like love and can actually be accompanied by love. But in the end, it’s not the same thing.

The surge in modern Neo-Pagan religions is driven in part by the embrace of Modern Pagans of full sexual expression. They recognize powers greater than themselves. They seek the help of those powers. They actually do embrace a sense of right and wrong in the world, importing from the East an idea of Karma, that the spiritual powers ensure people get what they deserve and the powers are especially against people “doing harm” to one another. But sex is defined as not harmful, as long as the parties involved are consensual.

So free sex, with any reason to feel guilt poo-pooed, is one of the major features of growing modern religions. Sex itself is increasingly seen as a virtue–as in, there’s someone wrong with someone who doesn’t want to have sex.

So the substitution of sex for love, sex as anti-love, replaces love as self-sacrifice as Christians have always understood it.

Anti-Faith and Anti-Hope

The book of Revelation features an unholy trinity of the Devil, “the Beast” (a.k.a. “the Antichrist”), and the “False Prophet.” What I’m affirming is the virtues of I Corinthians 13 (sometimes called the “theological virtues”) also have their substitutes. Sex is the anti-love. So what are anti-faith and anti-hope?

Faith in Christianity is not a generalized trust in anyone–it specifically means to trust God. So anti-faith is to believe in people rather than God. To put it in terms of what Batman said in The Dark Knight, to believe that there still is good in the people of Gotham. Or to apply the faith in people underlying Star Trek, the notion that someday we will be able to solve all our problems on our own, to completely eliminate poverty and crime.

Or course not all modern persons have strong faith in people, but the idea that people are generally good and generally can be trusted to do right, that evil is a pathology and not a condition that’s fixed feature of the human race is a pretty common aspect of modern human beings. And fits nicely into the anti-love principle, where people see love as an act of mutual gratification between consenting humans.

The Bible, on the other hand, does not envision that human beings will ever be able to solve all their problems on their own and does not see people in general as trustworthy (e.g. John 2:24-25). While we should be able to have some trust in our fellow humans, theological faith is directed at God himself, in an important contrast with anti-faith.

Hope in the Bible I’d say is related to faith. Hope is like faith, but for things that haven’t happened yet. Hope is faith’s future tense.

Hope can refer to multiple things in the future but when the New Testament talks about hope, it often refers to looking forward to either the resurrection of the body from the grave (e.g. I Peter 1:3) or looks forward to Jesus’s return (e.g. Titus 2:13). What’s the anti-hope that substitutes for that?

Generally, most people put their hope in this life, in this world. Generally, people avoid thinking about what could happen to them in the distant future, which is why even mentioning life after death, even if kindly, seems incredibly rude to them–they don’t want to think about it and don’t want to talk about it.

Though there is a new form of hope that directly relates to speculative fiction…

Science and Singularity as a Source of Anti-Hope

For some people, hope in the future is linked to the idea that science will be able to solve our modern problems. Science will cure hunger. Science will fix our medical woes. Science will even cure mean people from being mean–there will be a pill for that!

The faith in science (or to be consistent, the “anti-faith” in science) culminates in the hope of some for “the Singularity,” a point in the future when artificial intelligence will become so prominent that human beings will merge with it, supposedly uploading our brains into networked systems, supposedly becoming de facto immortal via strictly scientific and technical means.

The Singularity envisioned. Source: DailyStar.co.uk

While only a small fraction of the human race are looking forward to the Singularity to provide them immortality, some do have that anti-hope. Which is in direct opposition to hope in Christ’s return or hope in a bodily resurrection.

Responding to the Anti-Virtues as Christian Speculative Fiction Writers

Speculative fiction, especially science fiction, has the power to create expectations for what human beings will see in the future. The fact that much of speculative fiction, especially science fiction, downplays the role of God by never mentioning him or only giving negative or pejorative references to God we of course undo by creating expectations via stories that God will continue to matter in the future–and in other worlds, where- or whenever those other worlds may be.

We also indirectly combat the desires to obtain anti-love, anti-faith, and anti-hope by simply writing characters for whom actual love, faith, and hope have meaning and power. Faith that doesn’t stray from showing actual problems but also shows real deliverance and help from God. Hope that shows how trusting God for the future is better than trusting the collective human race or science.

Which leads to a potential approach to take in dealing with anti-love, anti-faith, and anti-hope. Write them as being central to people’s lives, but make the story a dystopia, in which the real needs of the human soul go neglected and where pleasuring the body just isn’t enough. Where the faith in people fails and the hope in science falls short.

Conclusion

So what do you readers think about my notion of sex as “anti-love” and the three theological virtues having modern substitutes? Has someone else said something along the same lines, only better and clearer than I did? đ Or similar? Please share.

And what stories do you know that effectively counter hopes for a future singularity and science-as-savior? Please mention them below!

in my face, I dropped her in a pond. I hope she could swim.”

in my face, I dropped her in a pond. I hope she could swim.”

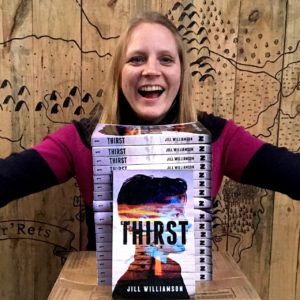

As it happens, speculative author Jill Williamson just released a novel in November, 2019, that now feels eerily spot on.

As it happens, speculative author Jill Williamson just released a novel in November, 2019, that now feels eerily spot on.  Now is the time to be good neighbors, to show kindness, to stay connected (and we are blessed with so many ways of staying connected electronically), and to pray.

Now is the time to be good neighbors, to show kindness, to stay connected (and we are blessed with so many ways of staying connected electronically), and to pray.

money!) people have thrown to the idea that the Egyptian gods were actually parasitic alien overlords, or that the Norse gods are still with us as magic space Vikings. But then, there are no votaries of either the Egyptian or Norse gods left. There is no belief to come into conflict with the story. Try a similar tack with a living religion and watch how fast things get ugly.

money!) people have thrown to the idea that the Egyptian gods were actually parasitic alien overlords, or that the Norse gods are still with us as magic space Vikings. But then, there are no votaries of either the Egyptian or Norse gods left. There is no belief to come into conflict with the story. Try a similar tack with a living religion and watch how fast things get ugly.

Of course, the externals are important. Who would want to replace the computer enhanced Aslan for an actor dressed in a lion costume? We want our Aslan to appear on the screen as a real lion.

Of course, the externals are important. Who would want to replace the computer enhanced Aslan for an actor dressed in a lion costume? We want our Aslan to appear on the screen as a real lion. Some time ago I watched the last part of Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers on TV shortly after re-reading the Lord Of The Rings trilogy. The main thing I noticed was conflict in the movie where none existed in the book.

Some time ago I watched the last part of Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers on TV shortly after re-reading the Lord Of The Rings trilogy. The main thing I noticed was conflict in the movie where none existed in the book. Another “it did not happen in the book” example also involved Aragon. On the way to Helms Deep (rather than to Isengard, as the book had it), the people of Rohan were attacked by Uruk-hai and Wargs. In the battle, Aragon was dragged over a cliff and fell to the river. His companions presumed him to be dead.

Another “it did not happen in the book” example also involved Aragon. On the way to Helms Deep (rather than to Isengard, as the book had it), the people of Rohan were attacked by Uruk-hai and Wargs. In the battle, Aragon was dragged over a cliff and fell to the river. His companions presumed him to be dead. In showing the strength of Faramir, the healing of ThĂ©oden, the prowess of Aragon, Tolkien enhanced Borimir’s failure, Denethor’s selfish choice, and Gandalf’s sacrifice. In other words, by not taking every character to the brink before leading them back, he magnified each case in which a character was taken to the brink.

In showing the strength of Faramir, the healing of ThĂ©oden, the prowess of Aragon, Tolkien enhanced Borimir’s failure, Denethor’s selfish choice, and Gandalf’s sacrifice. In other words, by not taking every character to the brink before leading them back, he magnified each case in which a character was taken to the brink.