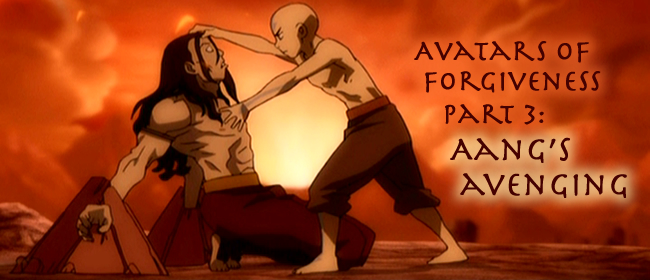

One month ago this conclusion to the Avatars of Forgiveness miniseries could have been very different. Its subtitle would have been ‚ÄúAang‚Äôs Mercy‚ÄĚ and its theme would have been about how Aang at the finale of Avatar: The Last Airbender (A:TLA) showed conviction and compassion by refusing to kill his enemy.

Then I thought more about what actually happened at the end of the fantastical animated series (all of which you must view via streaming or library DVDs before you read this).

What actually happens is the same as happens in any story in which a good hero chooses not to avenge himself against an enemy and instead rejects his own vengeful desires to kill the villain, and/or seeks to redeem him, and/or lets ‚Äúfate‚ÄĚ take care of him.

In many of these stories, it’s actually no great mercy to spare the life of an unrepentant foe.

Instead, sparing the enemy’s life is the worst thing a hero could possibly do to a villain.

‚ÄėThere‚Äôs got to be another way‚Äô

A:TLA turns the story toward a thematic journey that is startling to find in a ‚Äúchildren‚Äôs show.‚ÄĚ In ‚ÄúThe Southern Raiders,‚ÄĚ Katara takes a ‚Äúfield trip‚ÄĚ with Zuko and addresses her impulse toward hateful vengeance (yet concludes the truth that one cannot technically forgive an unrepentant offender). She forgives her repentant enemy, then departs.

Zuko: You were right about what Katara needed. Violence wasn’t the answer.

Aang: (with innocent confidence) It never is.

Zuko: Then I have a question for you. (He turns to face Aang.) What are you going to do when you face my father?

(Aang is suddenly shocked as the possibility dawns on him.)

Since the story‚Äôs beginning, viewers have learned that Zuko‚Äôs father, the evil Fire Lord Ozai, has inherited a ruthless three-generation empire ‚ÄĒ the Fire Nation. Ozai is a total dictator who not only dominates the world‚Äôs nations from a distance, but personally wounded and banished his own son from his homeland. Moreover, Zuko knows how it is to confront the Fire Lord. In ‚ÄúThe Day of Black Sun, Part 2: The Eclipse,‚ÄĚ the former Fire Nation loyalist and enemy of Aang repents and promises his father will be called to account for his sins.

Since the story‚Äôs beginning, viewers have learned that Zuko‚Äôs father, the evil Fire Lord Ozai, has inherited a ruthless three-generation empire ‚ÄĒ the Fire Nation. Ozai is a total dictator who not only dominates the world‚Äôs nations from a distance, but personally wounded and banished his own son from his homeland. Moreover, Zuko knows how it is to confront the Fire Lord. In ‚ÄúThe Day of Black Sun, Part 2: The Eclipse,‚ÄĚ the former Fire Nation loyalist and enemy of Aang repents and promises his father will be called to account for his sins.

Zuko: I’ve come to an even more important decision. (He closes his eyes and pauses.) I’m going to join the Avatar, and I’m going to help him defeat you.

Ozai: (Smugly) Reeeally? Since you’re a full-blown traitor now and you want me gone, why wait? I’m powerless. You’ve got your swords. Why don’t you just do it now?

Zuko: Because I know my own destiny. Taking you down is the Avatar’s destiny. (He puts away his swords.) Goodbye.

Zuko refuses his own vengeance and leaves it to a higher power, in this case the messianic Avatar who represents the world and maintains its moral balance. But now the time has come for Aang to fulfill what everyone agrees is his destiny: to stop the Fire Lord by any means and end the war. But Aang can’t do it. His lost people’s pacifism binds his conscience and he cannot reconcile this conviction with his responsibility as the Avatar to avenge evil.

As the story’s epic four-part finale begins, Aang and his friends are still recuperating in an unlikely refuge inside enemy territory: the Fire Lord’s own beach house on Ember Island.

Katara: I was looking for cooking pots in the attic, and I found this! (She unravels a scroll that shows a painting of a happy dark-haired baby playing at the beach.) Look at baby Zuko. Isn’t he cute?

Katara: I was looking for cooking pots in the attic, and I found this! (She unravels a scroll that shows a painting of a happy dark-haired baby playing at the beach.) Look at baby Zuko. Isn’t he cute?

(All the others laugh ‚ÄĒ except Zuko.)

Katara: Oh, lighten up. I’m just teasing.

Zuko: That’s not me. It’s my father.

(The others fall silent. Katara rolls up the scroll.)

Suki: But he looks so sweet and innocent.

Zuko: Well, that sweet little kid grew up to be a monster, and the worst father in the history of fathers.

Aang: But he’s still a human being.

Zuko: You’re going to defend him?

Aang: (calmly) No, I agree with you. (He stands.) Fire Lord Ozai is a horrible person and the world would probably be better off without him. But there’s got to be another way.

Zuko: Like what?

Aang: I don’t know. (He perks up and speaks faster.) Maybe we can make some big pots of glue, and then I can use gluebending to stick his arms and legs together so he can’t bend anymore!

Zuko: (with faux-eagerness) Yeah! Then you can show him his baby pictures, and all those happy memories will make him good again!

Aang: (sincerely and excitedly) Do you really think that would work?

Zuko: (angrily) No!

Aang: (He sighs and paces.) This goes against everything I learned from the monks. I can’t just go around wiping out people I don’t like.

Sokka: Sure you can. You’re the Avatar. If it’s in the name of keeping balance, I’m pretty sure the universe will forgive you.

Aang: (Turns back to Sokka and shouts louder than Zuko.) This isn’t a joke, Sokka! None of you understand the position I’m in!

Katara: Aang, we do understand. It‚Äôs just ‚ÄĒ

Aang: Just what, Katara? What?!

Katara: We’re trying to help!

Aang: Then when you figure out a way for me to beat the Fire Lord without taking his life, I’d love to hear it! (He walks away.)

Do you believe Aang can save the world?

In A:TLA the language, minor themes, and symbols are decidedly Eastern-influenced but the foundation is almost explicitly Christian. Aang rightly recognizes that even the evil Ozai is a human being ‚ÄĒ and even evil human beings bear the image of God. Aang grew up being taught to respect all forms of life. Aang faces a choice even more difficult than that of a sincere pacifist who is drafted to military service: he can‚Äôt conscientiously object. He‚Äôs the Avatar. It is his duty to save the world.

After his confrontation with his friends, Aang vanishes. He ends up on the back of a floating forest born by an ancient mythological creature: a lion turtle. This fantastical world never shows mystical sentience but does display a sense of fate/justice, and has come to his aid.

‚ÄėNow you shall pay the ultimate price‚Äô

Finally Aang confronts the Fire Lord. The battle is spectacular as the Avatar and his enemy clash in the skies, both empowered with super-firebending granted by a blazing comet.

Finally Aang confronts the Fire Lord. The battle is spectacular as the Avatar and his enemy clash in the skies, both empowered with super-firebending granted by a blazing comet.

Repeatedly Ozai appears near victory. Then Aang‚Äôs supernatural ‚Äúavatar state‚ÄĚ kicks in. Up he rises surrounded by a whirling mass of all four elements ‚ÄĒ water, earth, fire, and air ‚ÄĒ and he pursues the panicked Ozai through another forest, this one of rock columns. At last Ozai is down. The Avatar speaks with the chorus of past Avatars who could be heard as a ‚Äúgreat cloud of witnesses,‚ÄĚ a heavenly pronouncement of righteous wrath on the evil one.

Aang: Fire Lord Ozai! you and your forefathers have devastated the balance of this world! And now you shall pay the ultimate price!

(As a terrified Ozai watches, Aang prepares his final attack. All four elements combine into a stream of death that spirals through the air and rockets toward Ozai‚Äôs heart ‚ÄĒ then at the last second dissolves. Aang regains control of himself. He slips out of the avatar state and floats to the ground. Ozai is freed as Aang quietly steps back.)

Aang: No. I’m not going to end it like this.

Ozai: (Angrily.) Even with all the power in the world, you are still weak!

(Ozai moves for one last attack ‚ÄĒ which Aang senses with his feet as taught by his earthbending master Toph. Aang stamps down. His foot lifts and drags up a pillar of earth, deflecting Ozai‚Äôs attack and binding him inside the rock. Aang circles Ozai. He raises another rock to bind Ozai‚Äôs other hand. Aang earthbends the rocks lower and forces Ozai to kneel. Ozai attempts one final fire breath attack, but Aang airbends it away. Aang steps closer, puts one hand on Ozai‚Äôs forehead and one on his chest.)

(Ozai moves for one last attack ‚ÄĒ which Aang senses with his feet as taught by his earthbending master Toph. Aang stamps down. His foot lifts and drags up a pillar of earth, deflecting Ozai‚Äôs attack and binding him inside the rock. Aang circles Ozai. He raises another rock to bind Ozai‚Äôs other hand. Aang earthbends the rocks lower and forces Ozai to kneel. Ozai attempts one final fire breath attack, but Aang airbends it away. Aang steps closer, puts one hand on Ozai‚Äôs forehead and one on his chest.)

[…]

(Aang completely takes over Ozai‚Äôs energy. A blazing beam of blue erupts into the sky, then vanishes. Ozai falls to the ground and Aang releases him. Ozai tries to rise and attack ‚ÄĒ but falls back exhausted.)

Ozai: What … what did you do to me?

Aang: I took away your firebending. You can’t use it to hurt or threaten anyone else ever again.

Ozai has kept his life, but lost his birthright to master the element of fire. He is emasculated. His humanity he keeps but his gift is ripped away by a righteous hand of justice. Later we see that Ozai himself is banished from his throne. Instead he is condemned to spend the rest of his ways in prison ‚ÄĒ a pit in which he can rage and hate but never again hurt others.

Yet Aang‚Äôs conscience is clear. He hasn‚Äôt gone around ‚Äúwiping out people‚ÄĚ he doesn‚Äôt like. He has fulfilled his destiny on behalf of a cause greater than himself, and yet honored life.

This is both mercy and justice. It’s mercy because Aang as a human respected the humanity of his enemy and refused to disrespect his life. It’s also justice because Aang as the Avatar listened to his predecessors’ advice and recognized that he must take action to stop the Fire Lord and bring him to account for his evil. Within the story Aang sees what fans outside the story have already been seeing and which honest fans of any story with villains can easily see: that the world, the story itself, the less-corrupt parts of our hearts cry out for justice.

You may already see what I meant about how this shows Aang’s rightful avenging. For even in his mercy, Aang has actually enacted the worst penalty that Ozai could possibly imagine.

Surely Ozai would have chosen death over a lifetime of powerlessness and suffering.

Ozai would have preferred his own merciful annihilation. But Aang sent him to Hell.

The end

The heroes of Avatar: The Last Airbender show Biblical pictures of repentance, forgiveness, refusal to avenge, and even willingness to enforce civil justice against evildoers in a manner that reflects Rom. 13.

- Zuko repents of his arrogance and evil against the Avatar and others, and with utter brokenness cries out to his good Uncle Iroh for forgiveness (part 1). This reflects the nature of Biblical repentance in which the evildoer renounces sin and lives a life of continued repentance ‚ÄĒ a life lived not for sin but for a Person greater than himself.

- Katara pursues her desire for vengeance on an enemy to its logical conclusion, and then finds she cannot follow through (part 2). Her story echoes the Biblical truth that vengeance belongs to God alone. Yet Katara and the story are honest about the nature of forgiveness: that while we may release our hate and vengeance and leave an offender to God (or in Avatar, to fate), we can’t yet forgive unrepentant evildoers. Yet Katara overcomes bitterness and genuinely forgives her repentant enemy, Zuko.

- Aang’s story reflects a Biblical picture of two perplexingly dual truths: that man is created in God’s image and yet must suffer the consequences for his evil, and that even forgiven people must serve as instruments of others’ consequences for sin.

Now that this series is finished, what did you think? Did you find other interpretations or themes that I may have missed? How does Avatar’s avatars match Scripture’s beauty and truth about forgiveness? How may they differ from Scripture or from our own images of forgiveness?

long-forgotten originators of folk tales did so without compunction. Even the novel proper – a relatively newfangled art form – has quite a history of mixing art with messages.

long-forgotten originators of folk tales did so without compunction. Even the novel proper Рa relatively newfangled art form Рhas quite a history of mixing art with messages. literature in the 1890s; whose The Napoleon of Notting Hill is, upon analysis, an exposition on patriotism; who in The Flying Inn created a courageous, intellectual villain whose raison d’être was the prohibition of alcohol.

literature in the 1890s; whose The Napoleon of Notting Hill is, upon analysis, an exposition on patriotism; who in The Flying Inn created a courageous, intellectual villain whose raison d’être was the prohibition of alcohol.

My focus is primarily on Return of the Jedi. For although it is criticized as the weakest of the original trilogy, I find it the most profound. Like the other films, it’s an epic fight against evil and for life and freedom. But it’s also something more. It’s a fight for the soul.

My focus is primarily on Return of the Jedi. For although it is criticized as the weakest of the original trilogy, I find it the most profound. Like the other films, it’s an epic fight against evil and for life and freedom. But it’s also something more. It’s a fight for the soul. ld be better for Darth Vader than to come back from it. Those words at the end – ‘I’ve got to save you.’ ‘You already have’ – show that even he knew the salvation that mattered most. It’s the spiritual danger and the spiritual triumph of Return of the Jedi that make me think of it as a profound film.

ld be better for Darth Vader than to come back from it. Those words at the end – ‘I’ve got to save you.’ ‘You already have’ – show that even he knew the salvation that mattered most. It’s the spiritual danger and the spiritual triumph of Return of the Jedi that make me think of it as a profound film.