‘S.H.I.E.L.D.’ and The Subversion Of Human Nature

Sept. 23 brings the season 2 premiere of the superhero/spy television series “Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.” Here’s how I explored the finale of S.H.I.E.L.D.’s first season.1

Thanks to the May 13, 2014 season 1 finale of ‚ÄúMarvel‚Äôs Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ, I feel vindicated about my hopes for the series and encouraged by its honest look at human nature.

In February 2013 Joss Whedon previewed The Avengers TV spinoff that would follow back-from-the-dead S.H.I.E.L.D. Agent Phil Coulson and his new team of spies in a series of stories set in the shared Marvel Cinematic Universe. Whedon said ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ would be ‚Äúa very hopeful show‚ÄĚ and even seemed to promise something remarkably angst-free, even G-rated. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs not about murder, and it‚Äôs not about crime, and it‚Äôs not people looking into their own belly buttons,‚ÄĚ Whedon said. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs about people who are trying to help each other.‚ÄĚ

This sounds swell, but in practice the premise came off unremarkable. Stories such as episode 7, ‚ÄúThe Hub,‚ÄĚ followed a slow ‚Äúmystery of the week‚ÄĚ formula. You didn‚Äôt need to be clairvoyant to predict how stock-brilliant-hacker-with-a-past Skye would get caught breaking into ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ files or how sleek professional-fighter Agent Ward would start respecting young tech-brainy Agent Fitz.

Some fans were discouraged by the season‚Äôs first stories and viewership dropped. But I was sure the ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ folks knew what they were doing. After all, other classic series such as Star Trek: The Next Generation took three seasons to get really good. And what happened to that other sci-fi series by Joss Whedon whose 14 episodes front-loaded the snappiest dialogue and deepest character development? Maybe ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ started off slow to avoid raising expectations too high for the inevitably lower-budget series and is saving the best for last.

The midseason finale ‚ÄúThe Bridge‚ÄĚ blew things up real well but felt like a cliffhanger-by-committee. Hulu quit giving away ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ and I was reluctant to buy more on Amazon.

‘Turn, Turn, Turn’

Then came Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and all the pundits who said ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ ¬†needed some shakeup got their wish times ten in episode 17, ‚ÄúTurn, Turn, Turn.‚ÄĚ Beware spoilers: all along, the benevolent agency ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ was infiltrated by double agents of Hydra, a society of Captain America‚Äôs gallery of neo-Nazi rogues. By the pivotal episode‚Äôs last seconds, viewers were shocked to find that one of ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ‚Äôs stars, Agent Ward ‚ÄĒ the handsome-yet-kinda-boring one ‚ÄĒ was also a Hydra agent.

This leads me to wonder whether some of ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ‚Äôs advance promotion ends up an act of stage patter. What about that promise of a family-friendly show about decent, heroic secret agents simply trying to make a difference? If I didn‚Äôt know better I‚Äôd say the TV suits shelved that idea real fast and ordered from the top down: ‚ÄúNeeds more double-crossing. Make one cast member evil. Add blood.‚ÄĚ Instead, this was the Marvel story plan all along.

Fans realized this planned plot twist was why they couldn’t get attached to Ward. Despite Ward’s sacrifices for others and good-guy behavior in 16 episodes, the detachment was by design. Unlike other stunt plot twists that come out of nowhere (I’m looking at you, Frozen) writers had all along planned Ward’s bent toward evil and made sure that it made sense.

‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ feels more truthful now that its stories explore such truths of human evil ‚ÄĒ and by name. In ‚ÄúRagtag‚ÄĚ we meet Ward‚Äôs teenage arson-prone self and watch him become recruited by Agent Garrett, who poses as a new father/mentor figure. We see Ward kill more agents, including attempted assassinations of his former friends, Agents Fitz and Simmons. Ward even commits visual media‚Äôs unpardonable sin: he shoots the dog.

Other thoughtful superhero stories such as The Dark Knight (2008) assume their villains are irredeemably evil, but ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ directly asks its heroes and fans: Is Ward born evil? Does he have the will to choose otherwise? Even before Ward‚Äôs shoot-the-dog sin the story has (so far) answered exactly according to a Reformed Christian catechism: Ward was born in sin and is totally depraved, and only an act of supernatural regeneration can save him.

But if you prefer emphasizing the human-free-will concept or seeing more reflections of redeemed man, ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ still has your back. After all, Agent Coulson and his allies must confront the total-depravity question on an organizational level. The ‚Äúbasically good‚ÄĚ big-government spy agency to which Coulson dedicated his life to help others turned out to be rotten to the core with Hydra worms. Can the agency be redeemed? In The Winter Soldier, Captain America answered with a flat no: the whole agency must go down. ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ takes another step. In the season finale ‚ÄúBeginning of the End,‚ÄĚ head spy Nick Fury (lengthy cameo by Samuel L. Jackson) charges Coulson to‚ÄĒas I suspected‚ÄĒforge a new S.H.I.E.L.D. The old evil-infested agency may be finished. But Coulson has a chance to redeem it.

‘S.H.I.E.L.D.’ of shattered faith

Marvel, when given a chance to take its unprecedented shared-universe superhero films to the small screen, chose to write stories that subvert na√Įve optimism about basically-decent government agencies and even human beings themselves.

What does this say about humans?

Clearly we do not believe our own press.

We may vote for real-life political leaders who promise basically-decent bureaucracies that only want to do some good. But we don’t trust big-government agencies in our fiction.

We may cheer for real-life heroes as if they‚Äôre beyond evil. But we understand completely when poser heroes in our fiction reveal their evil nature‚ÄĒand we favor their punishment.

Make no mistake: ‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ is still optimistic, still a series about true heroes, and still relatively family-friendly (but hide the children‚Äôs eyes or perhaps your own in moments such as in the season finale when evil Agent John Garrett lunges at the military general). But its subversion of human nature reflects the Scripture‚Äôs truth: ‚ÄúThe heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick.‚ÄĚ By the season finale even the ‚Äúresurrected‚ÄĚ Agent Phil Coulson reveals lingering potential for unwitting evil. ‚ÄúNone is righteous, no, not one.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúS.H.I.E.L.D.‚ÄĚ offers hope that evil agents are punished and good agents can restrain evil and manage to be a force for good.

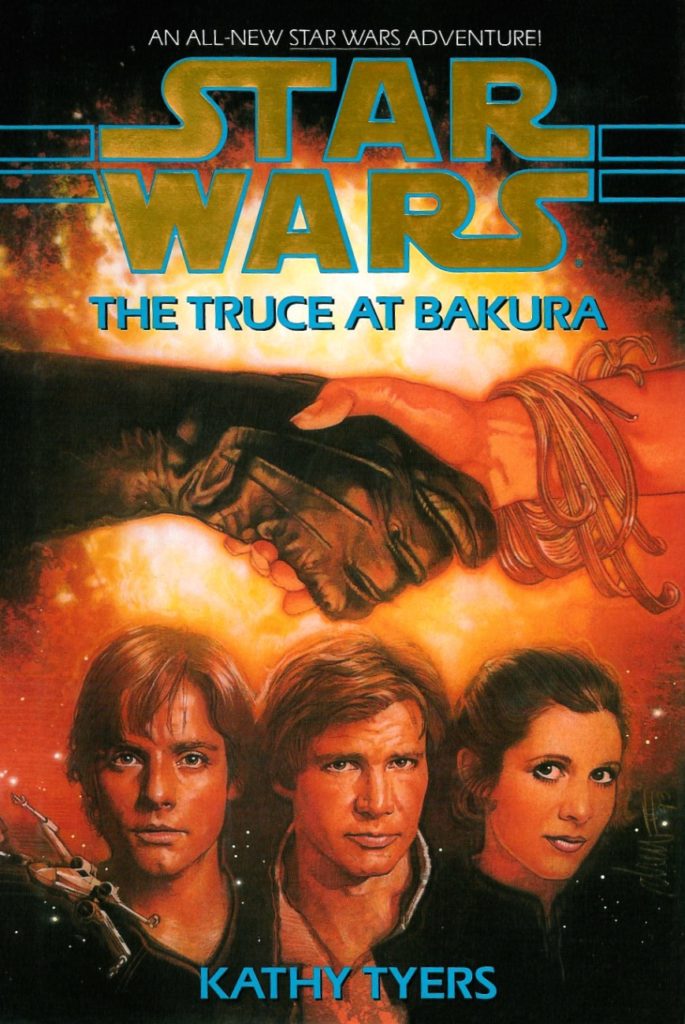

The great majority of reviews give an inadequate or misleading account of the book that is dealt with. … [P]eople sometimes suggest that the solution lies in getting book reviewing out of the hands of hacks. Books on specialised subjects ought to be dealt with by experts, and on theother hand a good deal of reviewing, especially of novels, might well be done by amateurs. Nearly every book is capable of arousing passionate feeling, if it is only a passionate dislike, in some or other reader, whose ideas about it would surely be worth more than those of a bored professional. But, unfortunately, as every editor knows, that kind of thing is very difficult to organise. George Orwell, “Confessions of a Book Reviewer”

The great majority of reviews give an inadequate or misleading account of the book that is dealt with. … [P]eople sometimes suggest that the solution lies in getting book reviewing out of the hands of hacks. Books on specialised subjects ought to be dealt with by experts, and on theother hand a good deal of reviewing, especially of novels, might well be done by amateurs. Nearly every book is capable of arousing passionate feeling, if it is only a passionate dislike, in some or other reader, whose ideas about it would surely be worth more than those of a bored professional. But, unfortunately, as every editor knows, that kind of thing is very difficult to organise. George Orwell, “Confessions of a Book Reviewer” aken for what they call a value judgment: Some people review books with an eye toward a whole genre, or an industry, or culture in general.

aken for what they call a value judgment: Some people review books with an eye toward a whole genre, or an industry, or culture in general.