Fiction Friday – Space Drifters By Paul Regnier

Space Drifters: The Emerald Enigma

(Enclave Publishing)

by Paul Regnier

Excerpt

Waking up to a fleet of Zormian star pirates surrounding my ship was yet another reminder that my life was not going as planned.

“This ship is loaded with thermal plasma canisters. You nail us with a photon canon and it’s lights out for all of us.” I glared up at the viewing screen and leaned forward in the captain’s chair trying to appear threatening.

“Lies. We ran a thorough scan of your freighter. There wasn’t a trace of thermal plasma.”

The Zormian slug captain’s generous, puke green torso folded over tight black stretchy pants in a hideous disregard for fashion. Though, to be fair, his velvet collar had style.

“They’re coated in Vathis cocoon slime. They can’t be scanned.”

“Impossible. Space trash like you can’t afford Vanthis slime.”

“. . . it was a gift,” I said.

Okay, I admit it was a weak story. I’d just woken up five freems ago and I was still groggy. I’d barely had time to step into my boots, grab my holster and throw on my lucky silver shirt and black kandrelian hide jacket. It wasn’t until I made it to the bridge that I realized I hadn’t changed my red-checkered pajama pants.

Not exactly the intimidating presence the captain of a starship hopes for.

Whispering gurgles and mutters trailed over the sub-space intercom. I took personal satisfaction that one of my lamest bluffs ever had prompted enough doubt for a hushed conference.

Though admittedly, Zormians aren’t very bright.

The bridge doors slid open with a chirp and Blix came strolling in, sinking his twin rows of sharp teeth into a golden spice pear. The overhead lights gleamed off his shiny copper scales. A brown bandoleer filled with small daggers criss-crossed his brawny torso and charcoal pants fit snuggly over his muscular reptilian legs.

“Where have you been?” I hissed through gritted teeth.

“I was hungry.” Blix joined me at the captain’s chair and looked at the viewing screen. “Zormians, huh? Savage creatures.”

I shot him an angry look and put a finger to my lips.

“We’d like to see the thermal canisters if you don’t mind.” The Zormian captain’s voice crackled over the antiquated intercom.

My shoulders sank, and my black jacked creaked against the chair. Bested by a Zormian. This was a dark day in the life of Glint Starcrost. I scratched at the three-day-old scruff on my cheek, wondering if this was the end of things.

“Thermal canisters?” Blix arched a scaly brow and grinned. His yellow eyes swirled with an orange smoke as his slivered pupils narrowed. He was taking delight in my misery. My life had taken some bad turns lately—the services of a star pilot, skilled as I was, were just not in demand these days. As such, I had taken to whatever odd jobs would keep me from going broke. This, of course, took me through some rather seedy star systems, teeming with the worst interstellar riffraff the universe had to offer. Run-ins with space trash like the Zormians was now my lot in life. My mind raced for a way out of this mess.

And then, inspiration hit.

“Did you say we?”

“Um, yes. I mean, what?” The Zormian was flustered.

“Well, I just thought it was strange you said, ‘We want to see the canisters.’ I thought you said you were the captain.

“No, not we. Me. You must show them to me,” the slug demanded.

“Okay, it’s just that you said ‘we’ like someone else was in charge over there. Are you sure you’re the one I should be talking to?” Messing with Zormian egos was a dangerous game but what choice did I have?

“I simply meant . . . that is . . . I took council that is all. I am in charge.”

Green ooze was dripping from his antenna and flowing into his seven bloodshot eyes. He was clearly upset. His gelatinous body rippled as he looked around in a rage. Behind him, a stout, pot-bellied Zormian was trying to fade into the shadows. No doubt he was the clever counselor working on a plan to steal leadership away from the current slug captain. It was a typical Zormian power grab, so far be it from me not to call attention to him.

“Is that him?” I pointed toward the retreating counselor. “Is that the real Zormian leader calling the shots here?”

The slug captain spun, all eight laser cannons drawn in a flash. The counselor drew his own cannons and they faced each other for a tense moment.

Zormians aren’t big on peace negotiations, but just in case, I thought I should speak up.

“Fire!”

They both unloaded their cannons and a myriad of red beams danced across the screen.

Chaos.

Smoke.

Gurgled screams.

Finally, the visual went black.

I exhaled and shook my arms to release the tension. Blix shook his head. “I can’t believe that actually worked.”

“Computer, switch to space view,” I said.

The screen remained black. After a moment, a female voice came over the ship communicator.

She sounded upset.

“A good morning might be nice.”

“Yes, right. Good morning, computer. Switch to space view.”

“You know I prefer ‘Iris.’ It’s so much more personal.”

About a century ago a group of meddlesome programmers thought it would be a great idea to add personalities to artificial life. The machines, realizing they were outfitted with emotion but lacked basic human senses, became disillusioned. Some turned unresponsive, others shut off completely. The remaining machines developed unhealthy personality traits. Iris is passive-aggressive. Sometimes technological advances take you back a few steps.

“Of course, Iris. Now how ’bout that space view, pretty please?” I tried to mask the frustration. Any outburst could send her weeping into the circuitry.

“Yes, of course, Captain. Or should I call you Glint?” Iris said.

“We’ve already had this discussion, Iris.”

“Iris sighed. “Oh, very well . . . Captain.”

A warbled blip sounded. The screen flashed to life and the grand blackness of space filled the screens, a vast choir of stars blinking behind three Zormian pirate vessels clustered in tight formation. Small red explosions dimpled the largest ship in the middle. It started drifting toward the nearest vessel.

“And you say you’re unlucky?” Blix said.

“I woke up to a hostile fleet of Zormians. You call that good luck?”

Blix shrugged. “You know, when I dreamt this, there was ten of them.”

I slammed my fist on the armrest. It hurt. Sometimes I wonder why I do that. “Why can’t you dream about wild fortunes or a relaxing vacation on the orange sands of Xerifities 12?”

“Preposterous. It’s obviously beyond my control what thoughts emerge.” Blix leaned against the half circle railing beside my chair. He took another bite of his pear and smirked. “But I must admit, it is wildly entertaining to watch you scramble. And look at the glorious results.” Blix motioned to the screen.

The main Zormian ship exploded in a huge ball of fire, starting a chain reaction that set the whole fleet ablaze. And they say words can never hurt you.

“Well done, Captain Starcrost.” Blix placed his arm over his chest and gave a theatrical bow.

Book Description

Space Heroes or Cosmic Rejects?

Captain Starcrost is not having the carefree, adventurous life of a star pilot promised in all the space academy brochures. He’s broke, his star freighter is in dire need of repair, and there’s a bounty on his head. His desperation has led to a foolhardy quest to find a fabled treasure that brings good fortune to the wearer, the emerald enigma.

Every captain needs a trusty starship and a crack team of crew members by their side. Unfortunately, the bitter pill of reality has brought him Iris, a ship computer with passive aggressive resistance to his commands; Blix, a hulking, copper-scaled, lizard man with an aversion to battle; Nelvan, a time-traveling teen from the past, oblivious to this new future; and Jasette, a beautiful but deadly bounty hunter looking to take over the ship.

Enter a charismatic and clever nemesis named Hamilton Von Drone, whose dark past has already intertwined with our misfortunate captain and left a painful scar. To complicate matters, as every good nemesis must by their evil nature do, Hamilton is employing his vast wealth on the very same quest for the emerald enigma.

Space Drifters: The Emerald Enigma is available at Amazon and many other fine outlets.

In the Superman II scene, Superman has fled Metropolis

In the Superman II scene, Superman has fled Metropolis In fact it is Man of Steel that takes Zodâs death (and the deaths of people in Metropolis) far more seriously than do the previous Superman films. Call it âgrimdarkâ or mock it for being more ârealisticâ if you wish. But the fact is that itâs the more-idyllic Superman films that treat death more lightly and Man of Steel that gets closer to showing death for what it is.

In fact it is Man of Steel that takes Zodâs death (and the deaths of people in Metropolis) far more seriously than do the previous Superman films. Call it âgrimdarkâ or mock it for being more ârealisticâ if you wish. But the fact is that itâs the more-idyllic Superman films that treat death more lightly and Man of Steel that gets closer to showing death for what it is. If youâre watching Man of Steel, donât expect a cartoon.

If youâre watching Man of Steel, donât expect a cartoon. Like Batman says at the end of Batman Begins: âI wonât kill you, but I donât have to save you.â Yeah, but … in the end, the result is the same.

Like Batman says at the end of Batman Begins: âI wonât kill you, but I donât have to save you.â Yeah, but … in the end, the result is the same.

Tolkien Reader, a collection of Tolkien works I have owned for years and only just read. It gives me real satisfaction to have read it; it makes me feel that there is some point to all those books that I bought on the cheap and that are now getting dusty in boxes, shelves, underneath my bed. My family has said I’ll never read them, as if anybody asked them.

Tolkien Reader, a collection of Tolkien works I have owned for years and only just read. It gives me real satisfaction to have read it; it makes me feel that there is some point to all those books that I bought on the cheap and that are now getting dusty in boxes, shelves, underneath my bed. My family has said I’ll never read them, as if anybody asked them.

Why would I say such a thing, you ask? Well, how is the storyâs conflict ultimately resolved? By the most bald-faced deus ex machina in blockbuster history: Superman makes a tough decision, Superman doesnât like the consequences of said decision, Superman flies around the earth fast enough to reverse its rotation (which makes no sense) and thus reverse time (which makes even less sense),

Why would I say such a thing, you ask? Well, how is the storyâs conflict ultimately resolved? By the most bald-faced deus ex machina in blockbuster history: Superman makes a tough decision, Superman doesnât like the consequences of said decision, Superman flies around the earth fast enough to reverse its rotation (which makes no sense) and thus reverse time (which makes even less sense),

Last week Fantasy Faction published an article entitled

Last week Fantasy Faction published an article entitled  One way to present a fantasy or science fiction world is as one originally good but spoiled. Narnia takes this approach as does Lewis’s space trilogy. Tolkien’s world is not as clearly good, but definitely the great need is to defeat the spoilers.

One way to present a fantasy or science fiction world is as one originally good but spoiled. Narnia takes this approach as does Lewis’s space trilogy. Tolkien’s world is not as clearly good, but definitely the great need is to defeat the spoilers.

To those who expected otherwise I would ask, âWhat did you expect?â Some might say, âSomething more like the Christopher Reeve Superman.â

To those who expected otherwise I would ask, âWhat did you expect?â Some might say, âSomething more like the Christopher Reeve Superman.â

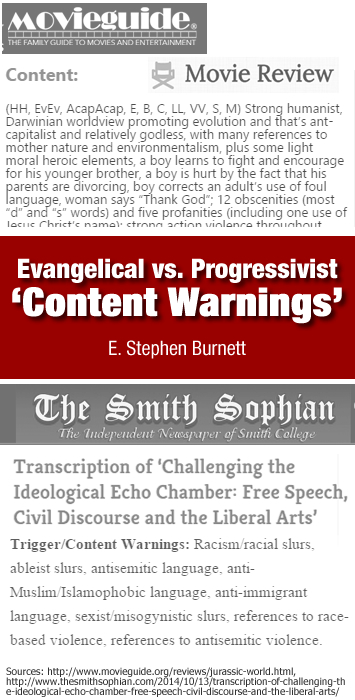

Letâs say a pundit has a large audience of people who trust him, and he decides âGilliganâs Islandâ ought to be banned or content-warned. He suggests the show is both racist (which it probably is in places) and filled with sexual innuendoes (which it also is in places). And letâs say other people, who are informed, respond with irritation at the would-be censor.

Letâs say a pundit has a large audience of people who trust him, and he decides âGilliganâs Islandâ ought to be banned or content-warned. He suggests the show is both racist (which it probably is in places) and filled with sexual innuendoes (which it also is in places). And letâs say other people, who are informed, respond with irritation at the would-be censor.

A magical Superman who always gets his way can answer none of those questions. Indeed, he canât even understand them. He can neither bear our griefs nor sympathize with our weaknesses. Heâs a false fantasy, a figment of wishful thinking.

A magical Superman who always gets his way can answer none of those questions. Indeed, he canât even understand them. He can neither bear our griefs nor sympathize with our weaknesses. Heâs a false fantasy, a figment of wishful thinking.

Of necessity, this post will include SPOILERS of the movie Jurassic World, a popular movie this summer. I think its high box-office rating was well earned because it did a lot of things right.

Of necessity, this post will include SPOILERS of the movie Jurassic World, a popular movie this summer. I think its high box-office rating was well earned because it did a lot of things right. One of the best parts of the movie as far as I’m concerned was the theme, which can best be summed up as “Family is more important than anything.” I thought it heart-wrenching that the younger son, Clay, knew his parents were planning to divorce, and I was impressed that the movie allowed the effect of divorce on children to seep through.

One of the best parts of the movie as far as I’m concerned was the theme, which can best be summed up as “Family is more important than anything.” I thought it heart-wrenching that the younger son, Clay, knew his parents were planning to divorce, and I was impressed that the movie allowed the effect of divorce on children to seep through. Of course others point out the incongruities in the movie—the ways they could have contained the Indominus Rex, the unlikelihood of teenage Zach Mitchell starting a Jeep that had been idle for 20 years, Aunt Claire outrunning a T-Rex in her high heels, and more. Nobody said the movie was flawless, but it was interesting and more worthwhile with its themes about the importance of connecting with and committing to people (and animals) than a lot of movies.

Of course others point out the incongruities in the movie—the ways they could have contained the Indominus Rex, the unlikelihood of teenage Zach Mitchell starting a Jeep that had been idle for 20 years, Aunt Claire outrunning a T-Rex in her high heels, and more. Nobody said the movie was flawless, but it was interesting and more worthwhile with its themes about the importance of connecting with and committing to people (and animals) than a lot of movies.