Badfan v Superman 2: Super-Nostalgia Knockdown

This week the San Diego Comic-Con is underway, complete with promotion for the summer 2016 followup to Man of Steel, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Meanwhile, SpecFaith staff explorers E. Stephen Burnett and Austin Gunderson share their conversation about Man of Steel and its controversial violence, and how the film flies over many criticsâ heads.

Catch up on part 1 from Tuesday or access the whole Badfan v Superman series so far.

Austin Gunderson: What, at first glance, would you say were the most significant differences â thematically, stylistically, and/or substantively â between Man of Steel and previous Superman films?

E. Stephen Burnett: My first point is your last phrase: I think people have a sort of âmy memory of the storyâ reference point regarding âprevious Superman films.â

I think theyâre recalling a recent popular culture mythology about the character of Superman that is based entirely on references and mental clips of the original Superman: The Movie, the unparalleled and classic 1978 film.

But when we start talking about âprevious Superman films,â that mythology breaks down.

Superman: The Movie

Superman: The Movie

First, Superman: The Movie (1978) was one of a kind. They caught lightning in a bottle. (But some flaws persist if you want to get nitpicky. For example, tonally itâs all over the place â the creators even described it as the equivalent of three films in one: Krypton is destroyed, Clark in Smallville, Superman in Metropolis.)

Superman II

Superman II (1981) was the result of a creative crisis between director Richard Donner and the producers whom most criticize today, the Salkind brothers.

Both films were shot simultaneously, a process unprecedented for its day. But once the first film was a hit, the Salkind Bros. went a bit mad with powerâagain, by the accounts Iâve heard and read. The Salkind Bros. fired Donner and hired another director, Richard Lester to replace him. And Lester, who liked comedy, put in some especially silly bits â the worst of which was a sudden stop to the story so that the three evil Kryptonians could super-blow Metropolis residents all over the place and cause all kinds of vaudeville-style hijinks.

Most of the good stuff in Superman II is from Donner, as evidenced by Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut, which released to disc-only in 2006 and, I think, should be considered the definitive film.

Most of the good stuff in Superman II is from Donner, as evidenced by Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut, which released to disc-only in 2006 and, I think, should be considered the definitive film.

But folks who have that stereotypical memory of the Superman character should remember: in either version of Superman II, Superman turns quite selfish and jerky, surrenders his powers, and goes a-fornicating.

Oh â and he kills General Zod.

Yes, the Christopher Reeve idyllic Superman tricks and de-superpowers General Zod his Fortress of Solitude. Superman even pretends to surrender and vindictively squeezes Zodâs hand before throwing him to his death.

Brute henchman Non arguably kills himself by trying to fly and instead falling to his doom. And Lois Lane kills the female Kryptonian, Ursa.

And why donât we notice?

Because … itâs treated more lightly. Itâs a fun killing. We must return to this point.

It hurts just seeing it.

Superman III

Superman III (1983) was idiotic and it demonstrates the worst of Lester with his âcomedyâ and circus-clowing cut loose. Letâs not even mention it except to say that no one needs to be favorably comparing it with any of todayâs Superman films.

For my part, when my original family was on a Superman film kick but I knew III was the worst, I tried to get through it (I have a high tolerance for films others despise), but simply couldnât make it. I walked out several times, tried to return, and then finally left after some villainess was cheesily turned into an evil cyborg or something.

Superman IV: The Quest for Peace

Superman IV (1987) was arguably even worse than Superman III and should serve as the final subversion of pop cultureâs romanticism not only with âprevious Superman films,â without qualification, but with actor Christopher Reeve in particular.

Yes, Reeve is an American hero. Yes, after his horseback riding accident he was even more an American hero. He died tragically young and weâll always remember him.

But Superman IV occurred when Reeve thought it would be cool to have Superman rid the world of all those nasty nuclear weapons and throw them into the sun. (I doubt even a kid with fanfiction could have come up with something so simplistic.) At least someone got in there and realized that this would only make things worse, because some villain would simply use the power vacuum to create an even worse weapon. And the results were super-idiotic. Iâve seen clips of the âbattlesâ on YouTube and television. Only in the old Superman series are visual effects from a 1987 film worse than a film made a whole decade earlier.

All that to say â when most people say âthe old Superman moviesâ they are only thinking of the first one and some of the second, or their memories of these.1

Yet between those two at their best and Man of Steel there are actual differences.

Superman 1978 plays out the heroâs journey in a very fun and comic-book-y way in a recognizable yet idyllic world with eras such as idealized-1950s and idealized-late-1970s.

Man of Steel takes this idea and adds some struggle: Supermanâs journey is still much the same, but this time itâs in a stylized version of reality that does seem more ârealisticâ not because itâs not action-film-land (it is) but because people react more realistically to the arrival of a superpowered alienâwith suspicion and fear and even religious responses as well as guns and military jets.

This is not a world in which the police would one minute react with comic incredulity at the notion of a flying hero in bright red boots, and the next minute simply go out for drinks to combat the ludicrous picture and then eventually accept it.

The first-contact situation in Superman 1978 goes like this: Superman tells Lois he comes from a world called Krypton and Lois says, âOh! Krypton,â and we move on.

The first-contact situation in Man of Steel embraces this science-fiction angle to a fault and we get a proper first-contact story: âYou are not alone,â and we feel that the world has really changed with this philosophy-shaking news.

Read part 3, Challenging Cheap Optimism, in which Austin Gunderson explains the chief obstacle to a new Superman story and how “Man of Steel” director Zach Snyder worked to overcome it.

- Edit: In part 4 of this series, Stephen will briefly touch on Bryan Singerâs retcon/sequel to the original Superman film series, Superman Returns. The film is under-appreciated, well-made, and built on nostalgia for âthe old Superman movies.â However, it arguably lacks the two better filmsâ sense of old-fashioned moral grounding. ↩

Also I recall I wrote this too:

Also I recall I wrote this too:

Back in 1865, US President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, the Civil War came to an end, William Booth founded the Salvation Army, Franz Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony” premiered, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson published Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland under he pen name, Lewis Carroll.

Back in 1865, US President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, the Civil War came to an end, William Booth founded the Salvation Army, Franz Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony” premiered, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson published Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland under he pen name, Lewis Carroll.  In may ways “Jabberwocky” is Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland in a nutshell. Inventive? YES! “Brillig” in its own way!

In may ways “Jabberwocky” is Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland in a nutshell. Inventive? YES! “Brillig” in its own way!

This is something I didnât fully grasp until I experienced it firsthand. I believed AViS was an interesting mental exercise. I allowed me to explore meaningful themes while trying to make the implausible, plausible. It was speculative fiction! Thatâs what I do!

This is something I didnât fully grasp until I experienced it firsthand. I believed AViS was an interesting mental exercise. I allowed me to explore meaningful themes while trying to make the implausible, plausible. It was speculative fiction! Thatâs what I do! With my earlier DarkTrench trilogy I speculated about a world under sharia law. The premise grew from the fact that there are some in the world who would like to see that very thing happen. Whether my particular vision of the future could realistically happen or not isnât important. The place of speculative fiction is to take an idea and extrapolate, to breathe it into life within the pages of the novel. To see what that version of the future might look like. One of the criticisms leveled against that series, however, was that I painted the culture as too bleak. That the denizens of this future sharia world were all bad or evil.

With my earlier DarkTrench trilogy I speculated about a world under sharia law. The premise grew from the fact that there are some in the world who would like to see that very thing happen. Whether my particular vision of the future could realistically happen or not isnât important. The place of speculative fiction is to take an idea and extrapolate, to breathe it into life within the pages of the novel. To see what that version of the future might look like. One of the criticisms leveled against that series, however, was that I painted the culture as too bleak. That the denizens of this future sharia world were all bad or evil. Are these speculations real concerns? And if they are, should Amish romance really be such a large part of the Christian market? I donât know, but I think it is something that bears discussion.

Are these speculations real concerns? And if they are, should Amish romance really be such a large part of the Christian market? I donât know, but I think it is something that bears discussion.

Or as Professor Kirke tells Lucy and the other Friends of Narnia in The Last Battle:

Or as Professor Kirke tells Lucy and the other Friends of Narnia in The Last Battle:

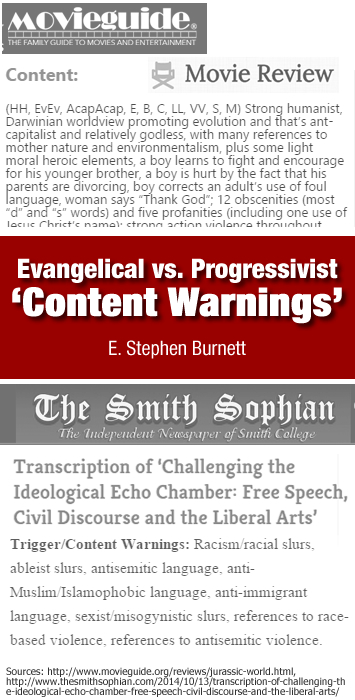

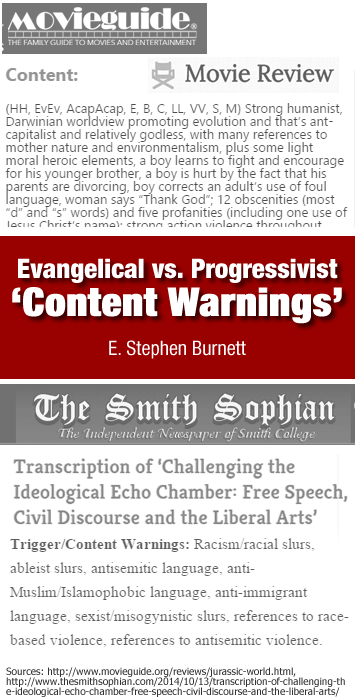

Lately Iâve found that we American evangelicals, bless our hearts, may have managed to set a cultural trend. Unfortunately Iâm not sure we can take pride in this accomplishment.

Lately Iâve found that we American evangelicals, bless our hearts, may have managed to set a cultural trend. Unfortunately Iâm not sure we can take pride in this accomplishment.