Are Heroes Passé?

Publishers Weekly sent out a typical mailing last week, this one with the subject line “The Fallâs Most Anticipated Novel is Almost Here . . .” As it turns out, this “most anticipated novel” is speculative. The promotion is for Six Of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, due to release late in September.

Publishers Weekly sent out a typical mailing last week, this one with the subject line “The Fallâs Most Anticipated Novel is Almost Here . . .” As it turns out, this “most anticipated novel” is speculative. The promotion is for Six Of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, due to release late in September.

The PW’s starred review said this story “has all the right elements to keep readers enthralled: a cunning leader with a plan for every occasion, nigh-impossible odds, an entertainingly combative team of skilled misfits, a twisty plot, and a nerve-wracking cliffhanger.”

And yet, it’s apparent it doesn’t have a hero. One librarian said this in her review: “Bardugo will have you rooting for the ‘bad’ guys and staying up reading way past your bedtime.” These “bad guys, descirbed as “six dangerous outcasts,” are

-

* A convict with a thirst for revenge

* A sharpshooter who can’t walk away from a wager

* A runaway with a privileged past

* A spy known as the Wraith

* A Hartrender using her magic to survive the slums

* A thief with a gift for unlikely escapes.

I’m reminded of other stories with “outlaw” heroes: Robin Hood, for example, or more recently a TV program called Leverage in which a group of con artists worked cons to bring justice for needy clients. Or what about White Collar, a TV program in which the main character is a criminal serving the remainder of his sentence by using his felonious talents to help the FBI.

Clearly there is some history in which flawed characters, as opposed to characters with flaws, surface as the individuals readers cheer for. We want to see justice win, even if those dispensing it are disreputable and use unsavory, even illegal, tactics.

In fact, we accept great flaws in our heroes, too. We don’t want our phones bugged, but if Jim Rockford or Thomas Magnum bugs the bad guy, illegal though it may be, we are happy if the tactic works. We don’t believe in torture, but when Jack Bauer tortures a terrorist to find out where the bomb is, we’re glad he’s on the side of right, doing what needs to be done to save the country.

Since there’s some history in fiction for such flawed heroes and even antiheroes, are we seeing a new trend or simply more of the same in books like Six Of Crows? In other words, are our choices now between bad guys and really bad guys?

I guess what I’m asking is this: have our tastes in fiction moved past the good guy? Is there no interest in a character who wants to be heroic and works to be heroic and succeeds at being heroic? Must all our heroes be reluctant or all our protagonists be “bad guys”? Have we come to an end of good guy heroes?

![]() Honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if that were true. We have placed such an emphasis on realism in fiction, and when we look around or look inside, we only see flawed people who don’t consider themselves heroes even when they do something heroic. They aren’t actually out to save the world. There are no actual Superman and Spiderman. The heroes of real life found themselves thrust into the role because of their circumstances, not because of their own choosing. And when the circumstances change, they are happy to return to regular life without the demand of saving other people from evil.

Honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if that were true. We have placed such an emphasis on realism in fiction, and when we look around or look inside, we only see flawed people who don’t consider themselves heroes even when they do something heroic. They aren’t actually out to save the world. There are no actual Superman and Spiderman. The heroes of real life found themselves thrust into the role because of their circumstances, not because of their own choosing. And when the circumstances change, they are happy to return to regular life without the demand of saving other people from evil.

Given that our stories, even our speculative stories, are required to contain a measure of realism, is the truly good hero of old, passĂ©? Will readers care for a hero who isn’t dark or who doesn’t have a “bad guy” tag, who isn’t fighting his inner vampire, who might just as well destroy the earth as save it?

Or is this merely a current trend that will one day soon fade away in light of a newer and “fresher” approach?

My short story Turncoat, set in the Quantum Mortis sci-fi universe and written with a very specific aim, was nominated this way: Last spring, Vox Day approached me about writing a short story for the Riding the Red Horse anthology. He saw it as a successor to Jerry Pournelleâs There Will be War. Since I had a genuinely good time writing the Quantum Mortis books, I agreed. Over the next few months, I brainstormed concepts, and wrote Turncoat in July.

My short story Turncoat, set in the Quantum Mortis sci-fi universe and written with a very specific aim, was nominated this way: Last spring, Vox Day approached me about writing a short story for the Riding the Red Horse anthology. He saw it as a successor to Jerry Pournelleâs There Will be War. Since I had a genuinely good time writing the Quantum Mortis books, I agreed. Over the next few months, I brainstormed concepts, and wrote Turncoat in July. Are they correct? My tastes in science fiction tend toward adventure rather than drama, so Iâve missed a lot of this preaching in the new works. Consider this: one of the most popular sci-fi books in recent years, The Martian, is going to be turned into a major movie. It is free of most preaching, except for one thing: the lone survivor triumphing over a hostile environment. Itâs also not up for any major awards.

Are they correct? My tastes in science fiction tend toward adventure rather than drama, so Iâve missed a lot of this preaching in the new works. Consider this: one of the most popular sci-fi books in recent years, The Martian, is going to be turned into a major movie. It is free of most preaching, except for one thing: the lone survivor triumphing over a hostile environment. Itâs also not up for any major awards.

The modern staple of zombie season is The Walking Dead, the series that just won’t die (heh heh). A cheap-looking knock-off on the SyFy Channel called Z Nation apparently received healthy enough ratings to merit a second season, and this year, we’re treated to some early preseason action in The Walking Dead prequel, the not-very-well-named Fear the Walking Dead. I watched the pilot episode this past weekend and I wasn’t terribly impressed. I’m not a big zombie fan to begin with, but I have been following The Walking Dead since the beginning and it’s held my attention through the years. Fear the Walking Dead, on the other hand, seems over-engineered and badly acted, at least as far as the first episode goes. It’s still too early to tell how the show will fare, and I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt for the time being.

The modern staple of zombie season is The Walking Dead, the series that just won’t die (heh heh). A cheap-looking knock-off on the SyFy Channel called Z Nation apparently received healthy enough ratings to merit a second season, and this year, we’re treated to some early preseason action in The Walking Dead prequel, the not-very-well-named Fear the Walking Dead. I watched the pilot episode this past weekend and I wasn’t terribly impressed. I’m not a big zombie fan to begin with, but I have been following The Walking Dead since the beginning and it’s held my attention through the years. Fear the Walking Dead, on the other hand, seems over-engineered and badly acted, at least as far as the first episode goes. It’s still too early to tell how the show will fare, and I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt for the time being.

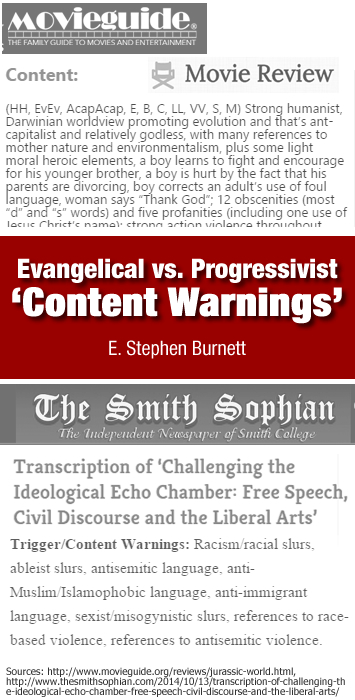

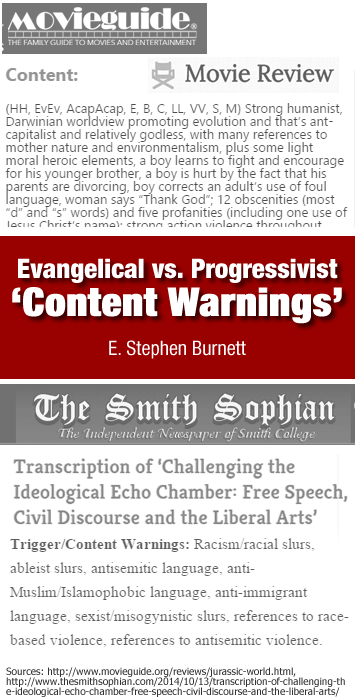

From time to time Christian evangelicals are criticized for our view of the arts. The critics believe something that is truly artistic can exist for no other purpose than to be truthful and beautiful. A song, a poem, a painting, a novel–none of those has to serve a greater purpose than to shine as art. In contrast, Christian evangelicals always want art to be functional–especially if the function is to declare something about God.

From time to time Christian evangelicals are criticized for our view of the arts. The critics believe something that is truly artistic can exist for no other purpose than to be truthful and beautiful. A song, a poem, a painting, a novel–none of those has to serve a greater purpose than to shine as art. In contrast, Christian evangelicals always want art to be functional–especially if the function is to declare something about God. If someone painted his portrait showing him as an angel of light, no matter how skillful the painting, it would still not be good art because it didn’t reveal truth.

If someone painted his portrait showing him as an angel of light, no matter how skillful the painting, it would still not be good art because it didn’t reveal truth. Tim Tebow comes to mind as an example of a man who is intentional in this regard. He wants others to know that at his core is this relationship with God that changes every other aspect of who he is.

Tim Tebow comes to mind as an example of a man who is intentional in this regard. He wants others to know that at his core is this relationship with God that changes every other aspect of who he is.

iry tales (or fiction generally) in the way that Tolkien did; they do not believe that the Great Eucatastrophe has âhallowedâ happy endings.

iry tales (or fiction generally) in the way that Tolkien did; they do not believe that the Great Eucatastrophe has âhallowedâ happy endings.

Realm Makers, the conference for Christian speculative writers, was a huge success, by all reports. For one thing, it created a good deal of buzz about the genre, but there may have been a more important effect.

Realm Makers, the conference for Christian speculative writers, was a huge success, by all reports. For one thing, it created a good deal of buzz about the genre, but there may have been a more important effect. Rather than bemoaning the state of publishing, we should pull up our socks and go to work. Yes, work! Good writing takes work, and we must not settle for mediocre. Proper marketing and promotion takes work, too.

Rather than bemoaning the state of publishing, we should pull up our socks and go to work. Yes, work! Good writing takes work, and we must not settle for mediocre. Proper marketing and promotion takes work, too.