Seven Final Challenges For Christian Movie Critics and Fans

What are moviesâincluding but not limited to Christian-made moviesâmeant to do?

If Christian movies are like Christian sermons, how should they play by sermon rules?

Do these films actually challenge people? Help people convert? Have any timeless appeal?

Those questions are from the first episode and second episode of the 21 Challenges for Christian Movie Critics and Fans. Hereâs the final episode, and this time I will risk beginning to offer some answers to my own questions. My thanks to readers for their sharpening me.

15. Critics: Are we being sensitive to fansâ movie-criticism stigmas?

If youâre familiar with âcontent warningsâ or âtrigger warnings,â among either evangelicals or progressivists, you may be tempted to laugh or shrug this off. Sometimes I feel the same. But the apostle Paul warns1 against doing something that is causing weaker brothers to stumble.2

In this case, what happens when a Christian movie fan hears a Christian critic blasting it?

I donât believe the fan would technically stumble per Paulâs warning. That is, the fan would not feel tempted to imitate the criticism of Christian movies but with sinful motives. But the fans could assume certain things about the reason for the criticâs condemnation, such as:

- âThat critic must not care how much the Christian movie meant to me personally.â

- âThat critic must be a compromiser with Big Hollywood and its anti-Christianity.â

- âThat critic doesnât care about evangelism or other moral values, only worldly Art.â

Is the Christian movie critic responsible for misinterpretations? Not at all. And yet Paul promotes care and love for people who might wrongly assume that your good action is actually evil. He says, âDo not let what you regard as good be spoken of as evil.â3 Iâm often re-learning this truth. If Iâm going to go out challenging or critiquing a Christian movie, I need to be sensitive to and respond to what fans will assume.

16. Fans: Are we being sensitive to criticsâ evangelical-culture stigmas?

You may love Christian movies and think theyâre not only amazing, but a great way to reach people who would not otherwise listen to Christians or visit a church. If so, have you also considered whether the actual nonbelievers you know feel the same way about the movies?

You may love Christian movies and think theyâre not only amazing, but a great way to reach people who would not otherwise listen to Christians or visit a church. If so, have you also considered whether the actual nonbelievers you know feel the same way about the movies?

Some people instead have stigmas about evangelical culture such as Christian movies, or even music or Thomas Kinkade paintings. Some non-Christiansâespecially if they grew up in certain evangelical backgroundsâreact to evangelical culture in the same way Christians (rightly) react to blasphemy or TV nudity. A non-Christian sees an evangelical-culture thing and assumes, âI gave that up when I was a child. Thatâs not worth my time.â4

At Christ and Pop Culture, Alan Noble puts it this way:

If we choose to embrace the Christian culture that is marketed to us, we run the risk of giving nonbelievers and new believers the impression that this culture is essential to the faith, that part of what it means to be a Christian is to accept a set of cultural tastes and interests. Even if we have the freedom to decorate our home with porcelain figures from the local Christian bookstore, to exclusively let our children watch Veggie Tales, and to listen to the Christian radio station, if these cultural choices come to define us as a community, then we can very easily present a false image of the faith. If we are more easily identified by our particular taste in movies than our love for each other, or if these become inseparable, then we have conflated the Gospel and the community of the Church with the social phenomenon that is Christianity.5

If non-Christians have such stigmas about Christian movies, then we need to rethink the reasons we like these movies (the challenge of question 2 in episode 1). At least, we must avoid saying things like, âChristian movies can reach unbelievers with biblical truth.â

17. Critics: Are we acting like anti-pop-culture evangelicals?

Once upon a time, most of the big movies were made by Big Hollywood. Evangelicals would see them sometimes, but usually condemn everything wrong with Big Hollywood.

And the evangelicals would not actually try to make any of the big movies themselves.

Today, some of the (relatively) big movies are made by Christians. Other Christians see them sometimes, but usually condemn everything wrong with the Christian movie-makers.

And most Christian movie critics do not actually try to make the big movies themselves.

Soâare critics incidentally turning into little but a complaining counter-culture? Are they vulnerable to the charge of, âI like my way of doing it better than your way of not doing itâ?

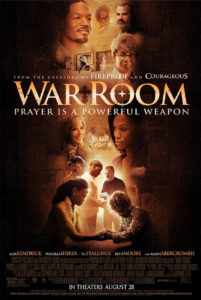

This challenge is partly untrue. Some Christians are trying to make their own films that are not typical family-friendly âChristian movies.â Iâve heard of examples, including a few independent Christian-made movies that acknowledge their limitations and try to value not only truth but excellent production value. But for whatever reason, these movies have not taken off like a War Room or a Godâs Not Dead.

Like it or not, thereâs a bigger audience for those popular movies than there is for, say, a Christian-made indie art-house drama.

Christian critics of poorly made, sentimental-story Christian films need to show, not just tell. And some need to make better films that appeal the popular level. Like how Jesus did.

18. Critics: Do we recognize the limits of Christian art and filmmaking?

Some critics who say we need better, deeper, hotter, expensive, more-biblical Christian movies need to be told just one little shutdown phrase: âOkay, that will be $70 million.â6

But what Christians need first may be even more expensive:

- A popular-level spread of biblical, gospel-based reasons to value popular culture.

- Christian teachers who publicly endorse popular-level yet excellent culture-making.

- Christian investors who finance organizations that grow culture-making talent and eventually finance high-profile movie productions. These productions could only be done in response to the newly made audienceâs natural desire for more challenging, fun films that make use of their faithâs prize natural resources (more on this below).

19. Critics: Do we think that âbasically add more swear wordsâ is a fix?

Imagine a movie in which an angry politician, exasperated business leader, or desperate action hero lets loose with an F-bomb. Depending on the context this can be offensive, understandable, or even seemingly ârequired.â

Imagine a movie in which an angry politician, exasperated business leader, or desperate action hero lets loose with an F-bomb. Depending on the context this can be offensive, understandable, or even seemingly ârequired.â

Now, imagine a Christian movie in which a wholesome Christian character depresses the verbal detonator. It wonât come across as anything other than awkward or even hilarious.

In fact, Iâve read some âedgyâ Christian fiction in which itâs obvious the author is playing with verbal matches. I can almost see the gleeful âHee hee, I lit up a word and set the page on fireâ grin on their faces. Or in a better context, you can see the author just awkwardly try out the Bad Words in a story context that does not even lend itself to the swear.

Like it or not, cussing isnât most evangelicalsâ native language. You may argue that it should be. Here Iâm ducking that issue. What I say is that âwholesomenessâ critics who awkwardly force such âedginessâ often look just as silly as the folks who enforce âwholesomeness.â

20. Critics: Are our âChristian movie reviewsâ really our reviews of fans?

Careful Christian reviewers avoid confusing movies and fans. But anecdotally I spy this impulse in myself and in other critics of sentimental and poorly made Christian movies.

For example, some negative War Room reviews say things like âThis idea could lead naĂŻve Christians to believe that âŠâ or, âThis part of the story could imply that âŠâ And this is a bad movie-review hermeneutic. This does not engage the movie on its own terms. This does not keep the movie itself separate from the fans weâre picturing in our headsâan imaginary crowd of evangelical magpies who snatch anything spiritually shiny without discernment.

Yes, these folks do exist. But they should not make cameo appearances in movie reviews. Anyway, lambasting them or their movies is not the way to challenge the problem.

21. Fans: Canât Christian movies more deeply mine the height and width and breadth and depth of our faithâs natural resources?

However, I must admit this: Most Christian movies emphasize overtly âspiritualâ things, especially the moment of salvation. This frustrates me. Not because I think the theme of salvation is boring, or so âmysteriousâ as to be meaningless, or clichĂ©, or âunartistic.â

Instead Iâm frustrated because the approach is almost always so limited.

Christian movies often act as if conversion (or re-dedication) is first a theatrical moment or a decision point, rather than a miraculousâyet quickly quantifiableâlife transformation.

Or as if the whole story must be about the conversion rather than what happens afterward.

The closest genre equivalent is the romance or romantic comedy in which the story does not start with an already-married couple but a pair of singles who, after ensuing hijinks, Learn to Love Again. I donât oppose this. I love these stories. But I also love other storiesâespecially fantastical ones.

Now imagine a theater full only of singles-find-love stories.

Is that what Christians want to be known for? As if Christianity is only about conversion or overt re-dedication events? What happens after salvation? I mean, what do we do in real life other than try to get other people saved, or Rededications, or Family Values?

I suspect many Christians think these are our best and thus most story-suitable qualities. Only when we explore the universe-rebuilding aspects of the gospel will we reconsider this.

Think like a pragmatist marketer who gets the raw materials of the Christian religion.

No, not the audience. Not the people in churches. The faith itself.

Imagine youâre a movie producer/writer. Lock yourself in a room with just the Bible and some of the classic works of theology written about it. Now write a movie story proposal.

Too much to start with? Then start the way pretty much every movie producer seems to be starting: Pre-existing name recognition from before the D.S.E (Smartphone Distraction Era).7 What do most people assume or know accurately about Christianity?

Too deep? Keep the theme popular but also deep. The best movies do both. How about:

Theodicy. As a recent conversation confirms, people hate/love exploring the issue of why an omnipotent God allows sin, and suffering. This is prime popular-Christian-movie material, especially if you honestly end with some questions unanswered.

Parables. Some Christian movies are adaptations of Jesusâs popular parables, yet with at best mixed results. This may be because they imagine a parableâs purpose is âto teach a moralâ or âto convert the hearer.â But âto reveal a truth about the Kingdom of Heaven that takes some digging to understandâ is closer to Jesusâs purpose in telling parables.

Epics. Christians, we keep forgetting we started the fantastical story genre. All of Western culture has been based on a Judeo-Christian worldview that includes God and creation and miracles and providence and redemption plus the true-myth version of the Heroâs Journey that has been a crux of stories for centuries. There is no reason to abandon this depth of our faith and leave it to be explored by secular filmmakers. We know the Hero of the Heroâs Journey. We may not have millions, but we have this creative âedge.â Why not mine the riches of our faith about Him and use those riches to finance our cinematic creativity?

- Romans 14, 1 Corinthians 8. ↩

- Note the wording: something that is causing. Paul is speaking about specific situations in which Christian A does a thing without sinful motive that makes Christian B want to do the same thing with a sinful motive. Paul is not telling all Christian As to preemptively avoid offending any potential Christian Bs out there. ↩

- Romans 14:16. ↩

- And in todayâs culture, with moralistic judgments based on progressivistic religion, non-Christians seeing evangelical culture increasingly think not only âThatâs worthlessâ but âthatâs evil.â ↩

- Rethinking the Stumbling Block: Christian Culture as a Barrier, Alan Noble at Christ and Pop Culture, Aug. 27, 2009 (emphasis added). ↩

- Or try this shutdown paragraph: âOkay, great. But while Iâm spending all the time being a starving artist or cultivating my filmmaking skills, who will help me eat? You see, a non-Christian may be able to get a lousy loft apartment in a downtown metropolis. But Christians ought to first obey Godâs command to provide for their familiesâand yes, most Christians also have families. Their health comes before my rags-to-riches artist story.â ↩

- This is why we getting movies based on board games and Pez dispensersâname recognition alone. ↩

ng to share a list of unrealistic things in fiction. And by unrealistic, I mean in the absolute sense of “not like reality”, and not in the vaguely literary sense that some people use the word. Realism, when applied to art, is a slippery term, and some day we need to have an enormous

ng to share a list of unrealistic things in fiction. And by unrealistic, I mean in the absolute sense of “not like reality”, and not in the vaguely literary sense that some people use the word. Realism, when applied to art, is a slippery term, and some day we need to have an enormous  Virtually all the “future” science you ever saw. If you have never considered what would actually happen if anyone followed Dr. Frankenstein’s theory on how to animate new creatures, you don’t want to start now. Suffice it to say that the whole theory is pseudo-science and could never animate anything. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is another classic that hinges on pseudo-science.

Virtually all the “future” science you ever saw. If you have never considered what would actually happen if anyone followed Dr. Frankenstein’s theory on how to animate new creatures, you don’t want to start now. Suffice it to say that the whole theory is pseudo-science and could never animate anything. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is another classic that hinges on pseudo-science.

Long before I’d heard of fantasy as a genre, I loved books that fall into that category. I was a child, after all, and had no problem with talking animals or Impossible Things. I loved to imagine, so Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride was a story to dream about. And I wasn’t steeped in politically correct-think, so the Uncle Remus stories such as

Long before I’d heard of fantasy as a genre, I loved books that fall into that category. I was a child, after all, and had no problem with talking animals or Impossible Things. I loved to imagine, so Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride was a story to dream about. And I wasn’t steeped in politically correct-think, so the Uncle Remus stories such as  Another author who is writing imaginative picture books (imaginative because the characters are animals), is

Another author who is writing imaginative picture books (imaginative because the characters are animals), is

That challenge leads to this one. As a rule, certain stories may end happily with the villains vanquished and the heroesâ dreams come true. But do critics challenge Christian moviesâincluding the recent War Roomâfor exactly the same ending? For example, one critic said:

That challenge leads to this one. As a rule, certain stories may end happily with the villains vanquished and the heroesâ dreams come true. But do critics challenge Christian moviesâincluding the recent War Roomâfor exactly the same ending? For example, one critic said:

Today is Labor Day in the US, so I thought it appropriate to think a little bit about speculative novels and work. My first thought was, Does anybody work? I mean, in epic fantasy, the protagonist and his crew are questing—traveling, for the most part, from one place to another in an effort to find, win, capture, or fulfill whatever the quest requires. Space opera doesn’t seem very different, but the principles are wondering the galaxy instead of roaming the countryside.

Today is Labor Day in the US, so I thought it appropriate to think a little bit about speculative novels and work. My first thought was, Does anybody work? I mean, in epic fantasy, the protagonist and his crew are questing—traveling, for the most part, from one place to another in an effort to find, win, capture, or fulfill whatever the quest requires. Space opera doesn’t seem very different, but the principles are wondering the galaxy instead of roaming the countryside. Star Trek, the original, included the same elements, (though, of course, the worker red shirts are inevitably the ones who die in a crisis). The spin-off series maintained that same bit of worldbuilding. Miles was the transporter chief and his wife a botanist. Deanna Troi was the ship’s counselor and Beverly Crusher, the chief medical officer.

Star Trek, the original, included the same elements, (though, of course, the worker red shirts are inevitably the ones who die in a crisis). The spin-off series maintained that same bit of worldbuilding. Miles was the transporter chief and his wife a botanist. Deanna Troi was the ship’s counselor and Beverly Crusher, the chief medical officer. Jill Williamson’s By Darkness Hid opens with the protagonist getting up early to feed the animals. It was his job as a slave. However, he quickly advances to become a squire, and off he goes on his quest.

Jill Williamson’s By Darkness Hid opens with the protagonist getting up early to feed the animals. It was his job as a slave. However, he quickly advances to become a squire, and off he goes on his quest.

A friend reminded me that itâs wise to ask Christian movie fans why they like movies such as Fireproof, Courageous, Godâs Not Dead, Heaven Is For Real, and the recent War Room.

A friend reminded me that itâs wise to ask Christian movie fans why they like movies such as Fireproof, Courageous, Godâs Not Dead, Heaven Is For Real, and the recent War Room. Let us go further. Letâs grant that Christian movies can be like sermons. (The opposite view seems legalistic.) In that case, the Christian movie must play by sermon rules. That means:

Let us go further. Letâs grant that Christian movies can be like sermons. (The opposite view seems legalistic.) In that case, the Christian movie must play by sermon rules. That means: I admit I thought this question as a response to War Room. I have not seen the film and will not review or critique it. But all promotions and reviews indicate the purpose of the film is in short to share a story that will help families and churches commit to prayer revival.

I admit I thought this question as a response to War Room. I have not seen the film and will not review or critique it. But all promotions and reviews indicate the purpose of the film is in short to share a story that will help families and churches commit to prayer revival.