Evangelical Vs. Progressivist Content Warnings 103

By now you have likely heard about “content warnings,” sometimes also called “trigger warnings.”1 And as we explored in part 101 and part 102 of this miniseries, these content warnings are often intended to prevent people from being exposed to content—such as images or words—that would presumably cause them harm.

By now you have likely heard about “content warnings,” sometimes also called “trigger warnings.”1 And as we explored in part 101 and part 102 of this miniseries, these content warnings are often intended to prevent people from being exposed to content—such as images or words—that would presumably cause them harm.

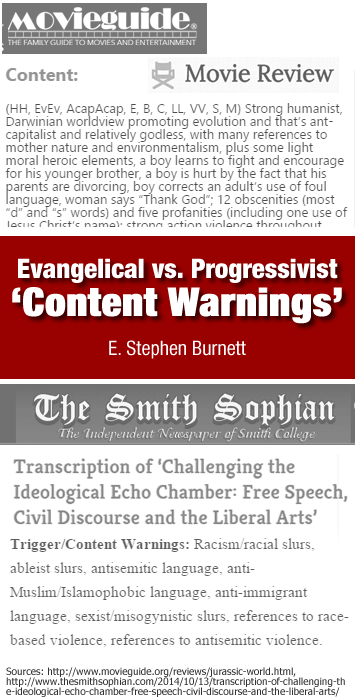

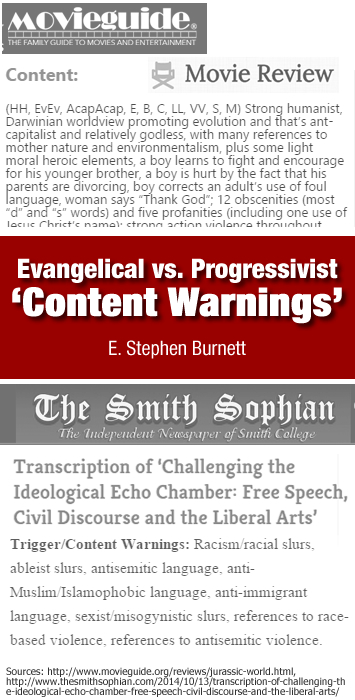

We’ve already talked about the fact that content warnings occur in two major religions:

- In progressivism, the idea is that victims of certain sins—such as racism or other kinds of abuse—should be protected from references or endorsements of this same sin.

- In evangelicalism, the idea is also that victims of sin—such as sexual content, violence, or swear words—must be protected from references or endorsements of these sins.

We’ve also explored how people who establish content warnings, the “protectors,” can have corrupt motivations.2 But now let’s discuss the folks who demand to benefit from content warnings—that is, the “protected.” These may ask secular college professors to shelter them from offensive words and ideas, or ask church leaders to shelter them from sin-temptations.

Whether among progressivist religion or evangelicalism, the assumption is this: “If I am protected from content, I will be safer.” From that comes a logical conclusion: “If I have been protected once and that helped me, then being protected a second time ought to be twice as helpful. And if I am being protected ten times more, that is ten times better.”3

And so on, until the content-warning becomes an indefinite process.

Such advocates may sincerely want protection. In some cases, they may struggle with real trauma or temptations. But they often miss one crucial problem: the warnings are at best temporary measures. They do not and cannot ultimately protect anyone from harm.

Here’s a personal example of “protection” from one type of trigger—personal temptation.

Stephen vs. the fantasy fearmongers

Some months ago a friend loaned my wife and me a DVD about how Harry Potter is evil, of the devil, and a corruption of innocent youth into actual witchcraft. I view this belief as not only unbiblical and nonsensical, but often harmful (and itself an example of “Christian” superstitious beliefs). I’m convinced of this viewpoint. But I don’t want to watch the DVD.

Why not?

Hulk smash puny Christian fantasy critic.

Because it’s a trigger. Even though I’m convinced of my viewpoint, it would take a lot of “working myself up to” the task of viewing this DVD and then getting ready, if necessary, to rebut the nonsense that’s in it. More likely by the end I would be hitting the ceiling and/or being tempted to head onto some social network somewhere to tell this Christian DVD maker, should he care to listen, exactly what I think of his mystical fantasy-fearful rhetoric.

Unbiblical, superstitious opposition to fantasy stories can be a “trigger” that makes me sin.

So how should I deal with this?

For now I’m dealing with it by not watching the DVD. (I don’t really have cause to watch it, anyway.) In other words, I’m content-warning myself. “Don’t watch it. It will only set you off and possibly make you commit sin.” But should I do that all the rest of my life? No. This measure should only be temporary. Even if the DVD teacher is teaching superstition as truth, if I can’t view this calmly and confidently and respond in that way, I’m the one who is sinning.4

Content warnings at best keep out infection; they cannot heal wounds

The example is not perfect. Here I’m speaking of a sin-causing “trigger,” a thing that makes me want to punch rhetorical walls. I haven’t yet spoken of the other kind of “trigger,” which may best be described as a post-traumatic stress trigger. This is an involuntary response to something you remember from sin-trauma, such as abuse or violence. We might think of military veterans who famously have trouble hearing fireworks or loud sounds without feeling either the unavoidable impulses to panic, find cover, or fight something back. Or we might consider blog posts about abuse by a spiritual leader.5

But without going into much detail about those sensitive issues, I can say this: I believe a biblical perspective of wholeness and resurrection will show that we ought to pursue similar healing for both triggers—both temptations to sin and PTSD-style responses.

Honestly, I don’t see a lot of that in the news reports and anecdotes about “trigger warning” activism on college campuses and such. Instead I see self-righteousness. I also see a lot of whining and first-world-problem-style laments. Among professing progressivists I see the same attitude I’ve seen from some fantasy-critical Christians. And when they do have trauma “trigger” issues with certain words or images or beliefs, they don’t seem to want to heal from them. They seem to want to cling to these weaknesses as if they were the same (in every case) as actual causes of temptations or severe post-traumatic stress reactions.

Such “victims” don’t want to heal. They want to pick at their actual scabs out of fun or idleness. Some of them may want even to cut themselves to bleed, form scabs, and then pick at them. Perhaps they may enjoy getting sympathy and even control over other people. Some evangelicals have called this the “tyranny of the weaker brother.”6

So how can Christians use content warnings in biblical perspective? The best Scriptural outline for content warnings may be in texts such as Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 8-10. These actually do address not the “weaker brother,” a uniform crowd, but “the one” who is weak, an individual who may need loving content-warning based on wisdom in a situation.

Apart from the Bible, we will veer into overprotectiveness or carelessness about “content” and sin-struggles. That’s where I’ll pick up for the next, and likely last, entry in this series.

- However, the term “trigger” could make people think about guns, which could itself be a trigger. In similar extreme cases, the very notion of a “content warning” or confronting a “microaggression” is itself seen as offensive or a microaggression. This was the case in one strange scenario at Brandeis University, according to Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in The Atlantic. ↩

- Some content warning “protectors” want to use these warnings to gain personal power or act out their own messiah complex. But responses to them are beyond the scope of this series. If someone believes or acts according to a belief like, “Other people are weaker than I am, so I will be the moral hero, and I will absorb the sinful content and protect them from themselves,” that’s a worse problem: pretending you are a fake “Jesus.” ↩

- At The Atlantic, Lukianoff and Haidt track several colliding social trends that produce growing adults who are trained to desire this kind of constant childlike overprotectiveness over themselves. However, they do not explore the inherent religious impulses—such as potential desires to manipulate others and stay “weak”—that can lead a person not only to tolerate his/her own sheltering, but to actively and even angrily demand more sheltering. ↩

- Note that I am trying to personalize the issue. This is SpecFaith and here I have a friendly audience. But even if someone attempts to “content warn” against Harry Potter and fantasy in general, we should not attempt to use the dark side of The Force to defeat our enemies by “content warning” against them and their corrupt poisonous influence. ↩

- In some cases, even Bible texts can unavoidably remind us of hurtful times. I still have trouble with Proverbs. ↩

- See for example The Tyranny of the Weaker Brother, sermon by R.C. Sproul at Ligonier Ministries. ↩

Just keep in mind for the PTSD type, they heal at their own rate and not as fast as you might think they should, so don’t try to dictate their recovery time to them. Feelings do not travel according to a schedule.

Fully agreed. And the same is true for those who need temporary “content warnings” to help them avoid sin-temptations. In some cases (but not all) those “content warnings” may need to last all their lives.

Enjoying this series! I read that Atlantic article a couple days ago and it “triggered” thoughts of this series – so I was glad to see it referenced here. 🙂

The point you make at the end about how it seems people enjoy their “victim” status is getting close to the crux of the matter, I think.

Thanks, Lisa.

And indeed, the most potentially accurate speculation about the cause also unfortunately sounds like the meanest conclusion: That the victim who does not even want to be healed (in theory) is enjoying manipulating other people on a power trip—all in the guise of not being powerful.

I think abuse of both kinds of triggers can come down to malaise.

“Sin triggers” are just a flavor of spiritual perfectionism, much like harassing people at the bus stop with salvation tracts or repeatedly going forward to “rededicate.” I was like that as a teenager. The burning desire to have a special place in God’s plan and to be one of the tiny minority who actually step up to do God work is a well documented weakness of evangelicalism, but I think for me the temptation was fear of being an incompetent loser. I think spiritual perfectionists are zealous about “sin triggers” because they need the need the spiritual experience to feel real and affirming.

I don’t think trying to manipulate people’s sympathy is the only way to abuse “PTS triggers.” A simpler explanation is that many of us first-worlders know that we have good and easy lives, but we’re still deeply unsatisfied with our lives. I’ve been ashamed that I’ve had it so good, and I’ve been ashamed of the fact that I’ve been unhappy and unproductive despite how good I’ve had it. Pop psychology encourages us to dig into our pasts to find explanations for our unhappiness, and we end up trying to sound wounded and bitter to convince others and ourselves that we’ve had a real life. I’ve teased cutting, making shallow scratches, wondering if blood would mean that I have REAL problems.

Do I have to threaten to find you and shove pills down your throat again? It’s like you’re working under the assumption that there is a limited amount of sympathy in the world and to qualify for some you have to have a 80% majority vote that your unhappiness is, indeed, legit.

Your dissatisfaction is legit in its own little snowflake way even if you’re not living in a third-world country’s open sewer. If materialism was all it took, then life would be a whole hell of a lot simpler. You don’t have to cut to qualify for help. Go find a professional wall to bounce things off. Do it, or I will make more empty threats at you.