A Little Imagination

It’s occurred to me lately that, for being one of the good guys, Jonah spends a lot of time being held up as a bad example. As  much as people talk about him, they almost never say anything good. Jonah was a prophet, but he gets no respect.

much as people talk about him, they almost never say anything good. Jonah was a prophet, but he gets no respect.

I would guess that it’s not the running away from God that we really hold against him. Adam hid from God, Jacob wrestled with God, Jonah ran from God: We can understand. What cements Jonah’s status as a Negative Example is the last chapter of his book, where it is revealed that he ran away because he wanted Nineveh to get blasted off the face of the earth. David was angry that God’s wrath broke out against Uzzah; Jonah was angry that God had compassion on Nineveh. So angry, in fact, that he wanted to die. Then his vine withered, and he was ready to die over that, too.

Jonah is often portrayed as something of a grouch, and there is reason for it. Anyone who is angry enough to die over a withered vine has anger issues. But you know something? I think we give Jonah short shrift. I think his performance, bad as it was, had better reasons than we give him credit for. People ask, “How could you not want God to have compassion?”

Let me tell you. Because I understand.

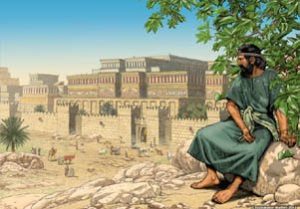

Nineveh was the capital of Assyria, the evil empire of Jonah’s day. Jonah saw Israel’s last revival of fortune, prophesying the great successes of Jeroboam II. But the stormclouds of Assyria soon overtook his victories: Within a decade of Jeroboam’s death, Assyria invaded Israel. Assyria would take territory and tribute from Israel until it finally destroyed Israel as a nation, ousting the Israelites from their homes and forcing them into exile.

Israel’s fate – death by Assyria – was by no means unique, nor surprising when it happened. The Book of Nahum – “an oracle concerning Nineveh” – is an instructive, if grim, companion to the Book of Jonah. Nineveh’s repentance did not last; neither did God’s forbearance. Nahum is all about God’s final judgment on Nineveh, and lays out the casus belli for the city’s destruction. Chapter 3 opens:

Woe to the city of blood,

full of lies,

full of plunder,

never without victims!

And a few verses down:

Many casualties,piles of dead,bodies without number,people stumbling over the corpses –all because of the wanton lust of a harlot,alluring, the mistress of sorceries,who enslaved nations by her prostitutionand peoples by her witchcraft.

So you can see why Jonah didn’t like them.

And he wasn’t the only one. This is how Nahum concluded the judgment against Nineveh:

Everyone who hears the news about you

claps his hands at your fall,

for who has not felt

your endless cruelty?

Jonah ends with the prophet angry that God had compassion on Nineveh. Nahum ends with Nineveh’s victims rejoicing that God had judged Nineveh. And if we can’t understand that joy – if we can’t understand why Jonah was angry that Nineveh wasn’t destroyed – it’s because we never had our own Nineveh, our own city of blood to fill our world with cruelty. There comes a time when you want justice, not mercy.

I am not arguing that Jonah was right. Jonah, who preached God’s undeserved mercy to Israel, had little right to complain of God’s undeserved mercy to Nineveh. Nor, as Jesus taught, are sinners like us in any position to demand grace for ourselves and sternness for others. Even justice was dealt out in the end: God did everything to Nineveh that Jonah could have wished. But He did it in His own time, and only after showing them mercy.

Jonah was wrong. But he was eminently understandable. It just takes a little imagination.

One of the greatest powers of fiction is its ability to present a viewpoint, to make us see through other eyes. There is no viewpoint harder to do justice to than one like Jonah’s – a viewpoint that is not only wrong but fundamentally unsympathetic. Have you ever read a book that made you understand, and even feel, a perspective you knew was skewed?

Excellent, thought provoking article Shannon (as usual).

In the VeggieTales Jonah movie, they sing, “Jonah was a prophet, but he never really got it.” Though none of us can really get our minds around God’s mercy, I do think that Jonah finally got it. After all, he wrote the book.

I enjoy novels that have alternating viewpoints between the protagonists and villains. It’s a way to see inside the villains’ heads and understand what makes them tick. Dean Koontz is especially adept at this. While his villains are often unsympathetic, the reader can at least understand why they act the way they do.

What a great question, Shannon! I agree with JS Bailey about Dean Koontz. His villains’ thoughts often fascinate me. Not that I want them to win, but it’s so interesting.

I’ve just reread The Host by Stephanie Meyer. It’s sci-fi, with parasitical aliens who go from planet to planet, using host bodies to live forever. They have no qualms about taking a body and effectively erasing the host’s mind and personality, although they retain all the memories of the host.

It all changes when this one “soul” (as they call themselves) comes to Earth, and the “body” (the host) refuses to be extinguished. Her thoughts remain in the soul’s thoughts and they are able to communicate with each other. The soul, Wanderer, discovers emotions she never felt before and because the body (Melanie) is able to talk to her, she begins to understand how wrong it is to take another’s body without their consent.

But I get why they do it. No one wants their own kind to become extinct, right? It’s a moral dilemma and it’s handled in a unique and wonderful way, in my opinion. The story moves a bit slow, but it’s worth the read.

“And if we can’t understand that joy – if we can’t understand why Jonah was angry that Nineveh wasn’t destroyed – it’s because we never had our own Nineveh, our own city of blood to fill our world with cruelty. There comes a time when you want justice, not mercy.”

It occurs to me that there might be great gnashing of teeth among Christians if God showed mercy to ISIS. After all those atrocities? Those beheadings and burnings? They’re like a modern-day example of Ninevite evil. Imagine if God sent one of us to deliver a message of condemnation and repentance! Their story might be similar to Jonah’s.

Girl, that is SO true. I imagine this is why Jesus said to love our enemies. No harder teaching than that, especially when you’ve been a victim.

I’ve read analysis of the book of Jonah being like a trickster myth, where the moral is taught by the character doing everything completely wrong. Switch out Coyote for Jonah and Water Sprinkler or Talking God for Judeo-Christian God, and it works pretty well.

More trickster motifs can be found in Elijah and the priests of Baal, or Samson and Delilah. Or that left-handed Judge who snuck a sword past a king ‘s bodyguard and stabbed him during a private audience. It’s a pity they skipped that one in youth group.