‘Doctor Who’: When Justice Seasons ‘Mercy’

Clearly showrunner Steven Moffat, scriptwriter Toby Whithouse, and the gang have been reading Speculative Faith and are thus crafting Doctor Who stories perfect for discussion.

Both recent episodes of series 7a touched on themes of evil, vengeance, and forgiveness.

Both recent episodes of series 7a touched on themes of evil, vengeance, and forgiveness.

Notice I said “touched on,” not fleshed out or explored. Like most stories, especially those by folks outside of God’s forgiveness, they have limits. Here I hope to explore those.

But first, a bit about Batman, from the 2005 film Batman Begins. (With some spoilers.)

Also a bit about Egyptians, embassies, and terrorists.

Bruce Wayne on trial

Ra’s al Ghul (posing as Henri Ducard): You are ready to become a member of the League of Shadows. But first, you must demonstrate your commitment to justice.

(They bring forward a captive, panicked man. Earlier Ducard told Bruce Wayne that the man was accused of crimes. They then force the man to kneel, and Bruce realizes they mean to ask him to kill the man now.)

Bruce: No. I’m no executioner.

Ra’s al Ghul: Your compassion is a weakness your enemies will not share.

Bruce: That’s why it’s so important. It separates us from them.

Ra’s al Ghul: You want to fight criminals. This man is a murderer.

Bruce: This man should be tried.

Ra’s al Ghul: By whom? Corrupt bureaucrats? Criminals mock society’s laws. You know this better than most.

Naturally the just-recently-ninja-trained Bruce Wayne finds a way to avoid being vigilante killer against the accused man, and (seemingly) bring down the entire headquarters of the League of Shadows. But that raises one question: did the accused man die anyway, in the melee? Also this one: what was Bruce’s preference over acting as an executioner?

He could have said, “No, if we kill or punish him for his crime, we’ll Become Just Like Him.”

Or, “Threatening or taking life is always wrong” (immediately betrayed by his ensuing self-defense during the fight and his own war against criminals).

Or worse, he could have said, “I am judge and jury, and I declare this man innocent.”

Instead Bruce simply and rightfully replied, “This man should be tried.”

That of course raises the question about what kind of judge should oversee the trial.

Terror suspects

One week ago as I write this, people in the nations of Egypt and Libya began raising a ruckus. Ultimately they killed the American ambassador to Libya and several others, and (in my view) raised a question many U.S. citizens naïvely hoped had been already answered by other people some years ago: what is the best response to radical “acts of terror”?

Some reply that the maker of an obscure, apparently Islam-mocking video should be put on trial or punished, made a scapegoat for the sins of the people.

Others more accurately say that such mobs tend to get worked up by many factors, and that it would have been impossible for them to have seen this obscure video. But among those — I heard one the other day — some accuse American leaders of promoting these sorts of crises out of political opportunism. So vote this November! Make them a scapegoat for sin.

Skipping here the Biblical truth that governments are tasked with enforcing some justice on Earth on God’s behalf, all of these are missing the point. Just as Doctor Who almost did.

The Doctor’s sin doctrine

(‘Ware spoilers.) In Dinosaurs On A Spaceship, the Doctor showed a shocking side: a desire for vengeance, leading to action. Apparently seeing a defenseless Triceratops killed pushed him too far. Suddenly the Doctor is shoving the villainous Solomon (played by David “Mr. Filch” Bradley) out an airlock, who’s later helpless as his ship careens into an explosion.

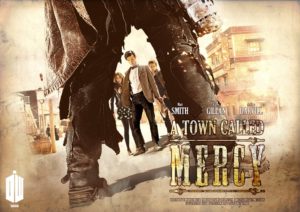

Last Saturday, such themes reprised. In an Old-Western town, the Doctor and his friends learn that a cyborg gunslinger wants to take vengeance on an alien resident. Then when the Doctor finds the harmless-appearing alien is a criminal who created the cyborg assassins, the Doctor is ready to throw the man out of town, a scapegoat in the wilderness.

The Doctor: We could end this right now. We could save everyone right now!

Amy Pond: This is not how we roll, and you know it. What’s happened to you, Doctor? When did killing someone become an option?

The Doctor: Jex has to answer for his crimes.

Amy: And what then? Are you going to hunt down everyone who’s made a gun or a bullet or a bomb?

The Doctor: But they keep coming back, don’t you see? Every time I negotiate, I try to understand. Well not today. No, today I honor the victims first. His, The Master’s, the Daleks’. All the people that died because of my mercy!

Amy: See this is what happens when you travel alone for too long. Well listen to me, Doctor, we can’t be like him. We have to be better than him.

The Doctor: Amelia Pond. Fine. Fine! We think of something else. But frankly, I’m betting on the Gunslinger.

Scenes like this are why we may enjoy great stories, not because they are all beautiful and truthful or because they are all controversial, but because they are often perplexingly both.

On the negative side:

- Another science-fiction staple: the wise, seemingly all-powerful alien and/or leader who is vulnerable to extremes, who needs a balanced Human Influence to sort him. Potential theme: our gods must work justice according to human views.

- “We have to be better than him” — as if this is the only humane justice. As if killing, a necessary evil, isn’t at least potentially a sobering choice in our sinful world.

- “Today I honor the victims first.” With this contradicted, we may doubt victims’ rights to be avenged.

On the positive side:

- Humans, even powerful ones, do have limited views and abilities to carry out justice.

- One person alone should not make such life-and-death decision. “Power corrupts.”

- Later in the episode, Jex realizes he must die to save the townspeople for whom he claimed to care. And he believes he will face justice. “In my culture, we believe that when you die your spirit has to climb a mountain, carrying the souls of everyone you wronged in your lifetime,” he says. “Imagine the weight I will have to lift.” And later: “I have to face the souls of those I’ve wronged. Perhaps they will be kind.”

This confirms a raw, refreshing honesty of Doctor Who, in particular this writer: honest touching on true justice must ultimately surrender the question. At least in this age. Our only assurance that killers will be punished or mercy shown lies beyond this life.

“This man should be tried,” Bruce Wayne gently admonished.

And who is the judge? Human beings? In one sense yes, per Romans 13, yet in our justice systems (which can be corrupt, as Ra’s al Ghul said) we can only begin to reflect the perfect justice God has in store beyond this age. He, as the One Who has been most sinned against — not people — is the true Judge. Only He has the right to choose when to show mercy and execute punishment. Moreover, He will not falter, or lunge about for a spontaneous scapegoat as we often do. All sin will be punished and His holiness vindicated, whether 2,000 years ago on the Cross, or for eternity in torturous separation from His presence.

Doctor Who misses that, though episodes such as A Town Called Mercy echo this truth. Perhaps more directly than the writers know.

The Preacher: He’s coming. Oh God, he’s coming!

Abraham: Preacher, say something.

The Preacher: Our Father, who art in Heaven. Hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done.

Who decides who lives or dies? The answer to The Question is “hidden in plain sight.”

The Doctor seems to have these moral struggles when he’s letting a companion go. Like on Waters of Mars. Without someone to keep him grounded, he might very well become the Master instead of the Doctor. (Would the Master have been a nuts as he is had he always had a companion? Who can say?)

And if you take the theory that he’s doing season seven in reverse order–having already said goodbye to the Ponds–it really intensifies that feeling. Amy points it out; “This is what happens when you travel alone too long.” And I think it’s gonna be worse for 11 than 10, since he’s had the Ponds for so long, as well as River’s role…

Side note about Dinosaurs on a Spaceship–it wasn’t just Tricey’s death that had the Doctor angry. It was the fact that Solomon had taken the entire crew of Silurians, woken them in small groups, and thrown them out the airlock when they refused to sell him the dinosaurs. Plus, he threatens Queen Nefertiti and plans to sell her as a slave. So it’s not quite the overreaction you’d think.

I think what really set the Doctor off here, deep down, is this idea of atonement. He’s still trying to atone for the Time War–I could provide examples–but he doesn’t think he’ll ever reach it, so it’s a sore spot for him.

I found this review particularly illuminating:

You wrote: “Honest touching on true justice must ultimately surrender the question. At least in this age. Our only assurance that killers will be punished or mercy shown lies beyond this life.”

Thank you for this insight. As writers, and especially as Christian writers (“if anyone speaks, let him speak as the oracles of God” –1 Peter 4:11), I think it is imperative that we search the scriptures, our own souls and query the Spirit for insight as to what questions have answers that we cannot know this side of the afterlife.

Stop pretending that everything is “black and white”. Stop pretending that there are easy answers to certain questions. And artfully point people towards eternity and the reality of it. Towards the questions it raises: If eternity is there, how will I spend it? How do my choices in this life matter to my eternity?

I haven’t seen Dark Knight Rises, but I vaguely remember Town Called Mercy bugging me ever so slightly.

Oh, Doctor, who needs to learn when to stop grandstanding about violence instead of putting a dang bullet in the villain’s head.

On Town Called Mercy, to me it wasn’t a matter of revenge. The gunslinger threatened the town. He needed to be dealt with. That was a very weird case in which both the victim and victimizer had done something worth death.

As for the dinosaur episode, I kept wanting them to throw the lecher out the window with the bad guy, so….

And hi. 0=)