What Propels Modern Steampunk?

I once read an article claiming that steampunk is an aesthetic rather than a proper fiction genre.

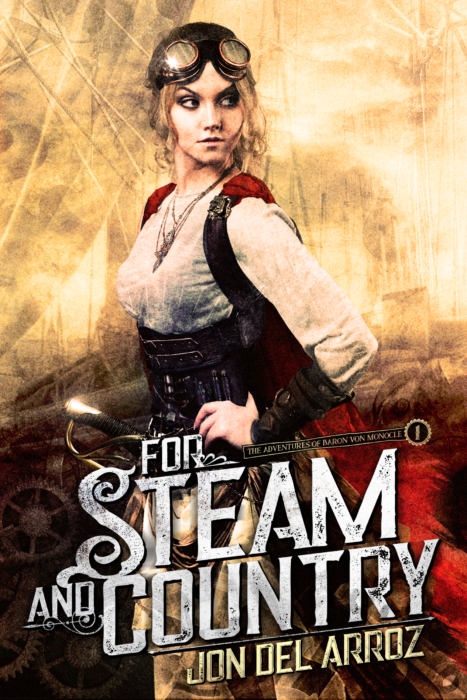

For a long time, I argued with this assertion, believing steampunk was more than just window dressing. But the more I delved into the genre, I found that in many ways, the claim was right. That aesthetic was something I wanted to see done in a specific way for a story, which is what led me to writing For Steam and Country.

Since the genre has fallen a bit out of the main public eye the last few years, here’s a little primer of what steampunk is and where I envisioned the genre going.

A brief history of steampunk

Steampunk is a catch-all term for Victorian-flavored fiction. Whether it’s set in 1800s England proper, or just using the way of dress and cultural flavors, steampunk is flavored much like one would see at a Dickens Faire, with ladies wearing corset and flowing dresses, men in dapper suits and top hats.

Steampunk is a catch-all term for Victorian-flavored fiction. Whether it’s set in 1800s England proper, or just using the way of dress and cultural flavors, steampunk is flavored much like one would see at a Dickens Faire, with ladies wearing corset and flowing dresses, men in dapper suits and top hats.

The “punk” often comes from leather and brass accessories added onto these looks, with goggles, monocles, holsters for strange contraptions. This all is often paired with alternative technologies developed from steam power, or imagined from various Tesla or Edison experiments. Most depictions of steampunk have some form of airship or dirigible in it.

The genre in fiction really began with Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, with Captain Nemo and his odd steam-powered submarine spurring the imagination of many. The next book to really capture steampunk flavor was much later, with The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, which very much brought about the modern aesthetic we think of a steampunk with its alternate history really giving birth to imaginative alternate technologies.

The steampunk aesthetic in modern fiction

In the early 2010s, steampunk exploded in the cosplay scene, with people holding entire “punk” Victorian balls at large conventions such as Dragon*Con. The costuming gave birth to Girl Genius, a web comic which received a lot of success. Fiction soon followed with popular series.

However, there wasn’t a clear style developing in the genre to match the aesthetic. Most of the books at the time fell into one of two categories: horror or romance. The first is best exemplified by Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker, which brought zombie fiction into a steampunk aesthetic. The latter was apparent in Gail Carriger’s Soulless or Cassandra Claire’s The Clockwork Princess. While both had fantastical elements to them, they at their core were romance novels.

But steampunk fell as an aesthetic into different genres. These were the settings used to tell tales that were clearly horror or paranormal romance. There wasn’t anything to define steampunk as a story itself.

I also wanted something a little different from the genre conventions. Thinking about Verne and the exciting costumes I was seeing around at different conventions, I was hoping more for swashbuckling fantasy adventures. I wanted exploration, airship battles, a use of the steampunk technology in a fantasy setting. The only place I’d seen steampunk used in this manner was in anime, with Studio Ghibli films such as Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle, or in the series Last Exile.

The birth of Zaira Von Monocle

Seeing nothing like that in the book market, I wanted to create that adventuring feel.

For Steam and Country was ultimately born out of a desire to see a different type of steampunk on the market, to present the adventure first and foremost. I wanted to capture the feel of what I’d seen in the costuming, as well as the feel of old video games like Final Fantasy VI, which also utilizes the steampunk flavor in a lot of its elements.

I crafted a coming of age story within a fantasy world with late 1800s technology. A kingdom that has a fleet of airships, where steam-engine powered horseless carriages are just starting to pop up. The airship is central to the story, the travel and the wide-eyed feel of exploring the world for the first time. I think those are the hallmarks of great fantasy and perhaps I just applied an aesthetic to a coming of age story and a hero’s journey, but For Steam and Country is what I always wanted the genre of steampunk to be.

Perhaps this is leading away from your article but… Several years ago I read Steve Rzasa’s “Crosswind” (followed by “Sandstorm”) Didn’t realize it at the time but are they steampunk? If so, where would you place them on your scale?