Serious Joy Saves Stories

Possibly I’ve found the secret to glimpsing more God-given happiness and wonder during Christmastime and any other season.

The answer: daring to risk holy, joyful seriousness about amazing truths and stories.

Two weeks ago, a drive-thru Nativity attraction reminded me of this fact. It led me to start this two-part article series about the opposite of joyful seriousness: the plague of flippancy in the church and in creative storytelling.

But the first article about the dangers of flippancy provoked some pushback from readers.

A few readers seemed uncertain about the difference between flippancy and other forms of humor, such as jokes. Some resisted strongly the notion that it’s never right to poke fun, or spoof, or employ “dark humor” about serious subjects.

I now wonder if this topic may bump against the specter of the Anti-Humor Christian.

Once I encountered this sort of person. She literally claimed that Jesus never ever would have laughed or said anything funny. (Despite the humor of many of His parables, especially obvious to their original hearers.) In her view, His sobriety over man’s sin and His mission to redeem people overruled any potential for humor in His life. That’s frankly a dangerous view. It strips the humanity from Christ. It effectively enslaves God to His own creation, forced to be “serious” by the threat of His rebellious creatures. And it leads to legalism against humor—a similar legalism we often see against stories.

So I don’t share the notion that any warning against flippancy—based on the words of C.S. Lewis through his fictional demon Screwtape—also warns against humor altogether. 1

I also don’t believe Lewis’s cautions about flippancy also rule out “dark humor” or “gallows humor.” I myself have found that I enjoy many stories that employ satirical and even dark-humor moments, such as the superhero satire The Tick (newly remade for Amazon Prime).

I also don’t believe Lewis’s cautions about flippancy also rule out “dark humor” or “gallows humor.” I myself have found that I enjoy many stories that employ satirical and even dark-humor moments, such as the superhero satire The Tick (newly remade for Amazon Prime).

It’s also true that in some sense, all this can be subjective. Like any human cultural element, humor and jokes can’t be quantified or classified. Even if they could be, I’m not a joke-ologist myself. In last week’s article, and in today’s, I’m mainly thinking aloud, having been inspired by both The Screwtape Letters and some popular stories’ seeming embrace of flippancy.

Warning: ‘flippant people’ with a prolonged ‘habit of flippancy’

In fact, if Lewis (or I) believed that it’s wrong to show a sense of humor about serious subjects altogether, we wouldn’t enjoy Lewis’s satirical The Screwtape Letters itself. After all, Lewis himself dares to act as the “clever human”—whom Screwtape dismisses—who attempts to “make a real Joke about virtue” (and about demons) throughout all 41 letters.

In fact, if Lewis (or I) believed that it’s wrong to show a sense of humor about serious subjects altogether, we wouldn’t enjoy Lewis’s satirical The Screwtape Letters itself. After all, Lewis himself dares to act as the “clever human”—whom Screwtape dismisses—who attempts to “make a real Joke about virtue” (and about demons) throughout all 41 letters.

Instead, Screwtape wants to train humans to speak “as if virtue were funny.” In Screwtape’s world, any of God’s good gifts, such as humor as well as “sleeping, washing, eating, drinking, making love, playing, praying, working … has to be twisted before it’s any use to us.”

In this case, Screwtape hates joy and laughter, which bring to mind Heaven’s music and which require far too much effort to “twist” or even create. He would rather cloud the minds of humans who haven’t even taken the effort to make the joke; instead they assume the joke has already been made.

However, Screwtape doesn’t praise mere flippant moments or dark humor, which in non-spiritually-twisted, non-habit-forming ways would be perfectly fine for humans to enjoy. So Lewis is not ruling out occasional jokes about serious subjects, even sacred subjects, so long as they do not presume the subjects themselves are automatically unserious.

For example, we might mock Satan, as Lewis does in his book, even while seeing spiritual threats in biblical light. We might “cast” a “riddikulus” spell against spooks that should not actually frighten biblical Christians who live in Jesus’s victory. Privately I might even make a dark-humor joke about some terrible event in a way that shows I’m anticipating the eventual empty threat of death. Or a series I enjoy, such as “The Tick,” can upend superhero tropes and even have moments we could call “flippancy” without actively mocking virtue.

However, these are moments of jocularity, even flippancy. They don’t represent a “prolonged” lifestyle or dominating influence that leads to what Screwtape calls “flippant people,” that is, humans who have become defined by constant ridicule of serious subjects.

Again, in Screwtape’s view, the flippant person is not a happy or joyful person. He or she is not excited to share jokes or to sharpen intellects by trading barbs. He or she is not even very creative; after all, they don’t even go to the effort of making actual flippant remarks.

But worst of all (to Screwtape, best of all), “the habit of Flippancy” makes a person resistant to God. Screwtape describes these folks as “steady, consistent scoffers and wordlings who without any spectacular crimes are progressing quietly and comfortably towards Our Father’s house [Hell].” And with his word “scoffers,” Screwtape brings his verbiage closer to that of Scripture, especially in the book of Proverbs, which constantly warns against “scoffers” and “mockers,” that is, people who do not laugh in God’s ways, but at them.

Flippancy’s cure: ‘happiness and wonder that makes you serious’

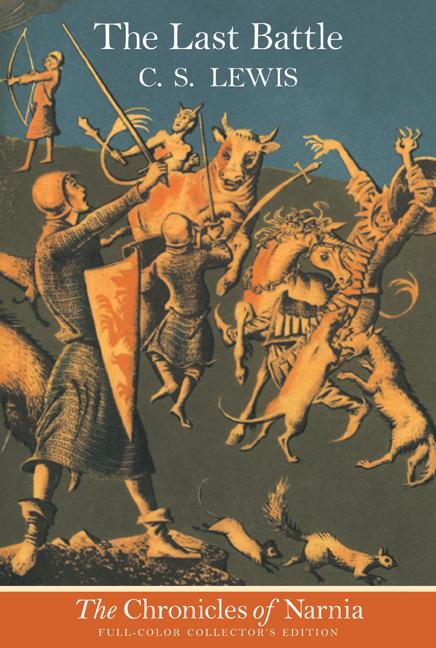

Lewis diagnosis the problem of weaponized, totalizing flippancy that leads to “flippant people.” But I suggest he also gives the solution in his other books. Chief among those may be The Chronicles of Narnia, which offers both character-driven humor and a prevailing sense of joy and virtue that the story-world holds absolutely apart from mockery or self-awareness.2 For Lewis, this joy and virtue are grounded in the person of Aslan and the wonders of his creation in Narnia and surrounding lands.

To get the most out of this story, you laugh alongside these wonders, not at them.

Moreover, Narnia is full of humorous moments, but never at the expense of Aslan or its own artful wonders. Its “jokes” don’t step on the horror of battle, the majesty of a mountain or city, the trauma of a dying mother, or worldwide destruction. (Meanwhile, some newer fantasies might feel they need to lighten the mood even among supposedly serious themes such as these, lest we consider them “pretentious” or feel the movie isn’t much “fun.”)

And in the final Narnia volume, The Last Battle, when the world of Narnia draws to its apocalypse, humor is the first blessing to leave. Only when our heroes’ fate is grim and absolutely serious can we feel the story’s weight. Only then, once we’re drawn into the even better world of Narnia-within-Narnia, can we laugh and yet also embrace joyful solemnity:

And in the final Narnia volume, The Last Battle, when the world of Narnia draws to its apocalypse, humor is the first blessing to leave. Only when our heroes’ fate is grim and absolutely serious can we feel the story’s weight. Only then, once we’re drawn into the even better world of Narnia-within-Narnia, can we laugh and yet also embrace joyful solemnity:

“But very quickly they all became grave again: for, as you know, there is a kind of happiness and wonder that makes you serious. It is too good to waste on jokes.”

I love that phrase: a kind of happiness and wonder that makes you serious.

Where is this sense in some new fantasy stories, including superhero and space-adventure films? Would a director or screenwriter feel it’s worth the risk to build up a scene based on this “happiness and wonder” and not “waste” the moment on jokes? Or may such a scene—or a film based entirely on this sensibility—trigger the dread fear of “pretentious” stories?

To be earnest, you gotta risk being pretentious. There are worse things to be, like cynical, angry, shallow, judgemental or repressed.

— Scott Derrickson (@scottderrickson) July 24, 2017

Apart from stories, I crave more of this emotion in the Christian world. Although we are making progress, some churches (especially of the mega- variety) in their “preaching” and singing still emphasize “fun” and maybe even flippancy as Christian alternatives to serious-inducing happiness and wonder. This is neither biblical nor helpful to our human growth.

At this time of year, Christmastime, such flippancy especially leaves an opening for fake “wonders,” such as materialistic consumerism, which can replace the calm, joyful, wide-eyed wonder of traditions such as Advent. When we’re constantly self-aware, looking for the “joke” that’s already been made about serious glories, and unwilling to suspend our disbelief, we close ourselves off from this emotional response to Jesus’s arrival among us.

But oh, the joy, when we forget about ourselves and surrender ourselves to this God-given joy and wonder. And oh, the wonder of practicing this surrender even when it comes to the humans around us—such as in our churches—who are training to help us find this joy.

Joyful seriousness = improved creativity in storytelling

At the Follow the Star event, actors who portray Mary and the angel Gabriel must repeat their postures for hours, without any room for flippancy or self-awareness.

Two weeks ago, I glimpsed just the back side of this happiness and wonder.

It occurred at an annual event hosted by a Lutheran church: the “Follow the Star” drive- and walk-thru attraction that portrays not only the Nativity but all of Jesus’s life.

At this attraction, there’s no room for self-awareness, deconstruction, or flippancy. Follow the Star is assembled by hundreds of volunteers and dozens of cast members. They must work for months to set up this thing. And then, three nights in a row, these cast members must take turns repeating the same biblical scene, over and over and over, with minimal breaks (and a few shift changes) and with no room for missing their lines or actions—or getting sick of doing the same thing repeatedly and therefore wanting to make light of it.

This was already impressive during the past years I’ve attended Follow the Star. However, this year organizers added something new: two cast members, standing by the sidewalk, to introduce upcoming scenes. I was struck by the second cast member, performing a Roman centurion, who stops the group before the Crucifixion scene. This man was utterly serious. He allowed no hint of self-awareness or “this is all a show” in his performance. And there on that sidewalk behind a mid-size Lutheran church in Cedar Park, Texas, he elevated this performance. He showed that he believed this. And his belief proved contagious to us all.

No, I don’t think Christians should always operate at this level of earnestness.

But are we comfortable with being earnest at all, either in our church ceremonies or in our art? Must we always feel compelled to be cracking wise backstage, in on the joke, or aware of the trope? Can we let go of our need to feel in control that way, and release ourselves to the dis-empowering but oh-so-liberating happiness and wonder that makes us serious?

I know I can’t. Not on my own. But it’s a goal I will pursue, at Christmas and in the new year.

- Once more, here is the complete quote from letter 11 of The Screwtape Letters:

Flippancy is the best (devilish use of humor) of all. In the first place it is very economical. … Among flippant people the joke is always assumed to have been made. No one actually makes it; but every serious subject is discussed in a manner which implies that they have already found a ridiculous side to it.

If prolonged, the habit of Flippancy builds up around a man the finest armour-plating against the Enemy that I know, and it is quite free from the dangers inherent in the other sources of laughter. It is a thousand miles away from joy: it deadens, instead of sharpening, the intellect; and it excites no affection between those who practise it … ↩

- Writers who adapted the first three Narnia books into films did not always follow this ethos. They often implied that “Narnian” virtue is either unnecessary or even worth laughing at, not alongside. ↩