Flippancy Kills Stories

People often act as though stories are made terrible mainly by profit motive, laziness, and sentimentality.

I disagree.

Sure, these problems constantly plague stories. Christians know that evangelical stories are especially haunted by all three wicked spirits. When, say, Christian movies are terrible, we can’t help suspecting their producers only make them for the money. Or they take shortcuts in craft or budget. Or they see the world, or pretend to see it, through sugar-coated lenses.

However, the most powerful story-haunt of all may be flippancy.

This threat is common to all three of the other threats. Yet I’ve begun to wonder if flippancy is more powerful than them all. This enemy threatens even stories we otherwise enjoy in both the “Christian” and non-Christian story arenas. Flippancy can ruin churches, social networks, romantic relationships, novel series, and even superhero movie franchises.

For Christian fans, flippancy plagues even our attempts to raise the value and readership of our favorite fantasy, science fiction, and supernatural/horror novels by Christian writers.

What is flippancy?

We could be clichéd—or even flippant—and fetch a dictionary definition for flippancy.

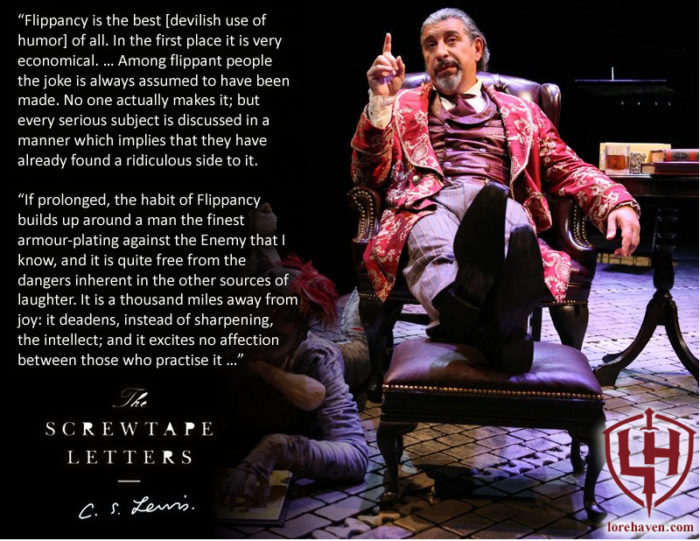

I prefer C.S. Lewis’s understanding as voiced in The Screwtape Letters. In letter 11 the demonic uncle/undersecretary Screwtape expounds on human humor. Ever the philosopher about everything, Screwtape classifies humor in four categories:

- Joy

- Fun

- The Joke Proper

- Flippancy

In Screwtape’s world, every good gift comes from God, including humor. All God’s gifts can be twisted by sinful humans—aided by influence by demons. So whenever Screwtape considers a topic, he’s the ultimate pragmatist: he sees any sin and any good enjoyment alike as useful to the cause of Hell, so long as it’s leading the human away from Jesus.

Thus, Screwtape all but throws out “joy” and “fun” as useful pursuits for demons to exploit.

He sees more promise in humor mode number 3, The Joke Proper. However, Screwtape the pragmatist prefers shortcuts around pitfalls to temptation methods. So he sees limited use for seemingly easy sins like plain old dirty jokes. In his view, even these kinds of bawdy jokes are not always associated with actual lustful thoughts or actions.

Far better, Screwtape argues, to promote flippancy as the most demon-friendly humor:

Flippancy is the best [devilish use of humor] of all. In the first place it is very economical. … Among flippant people the joke is always assumed to have been made. No one actually makes it; but every serious subject is discussed in a manner which implies that they have already found a ridiculous side to it.

If prolonged, the habit of Flippancy builds up around a man the finest armour-plating against the Enemy that I know, and it is quite free from the dangers inherent in the other sources of laughter. It is a thousand miles away from joy: it deadens, instead of sharpening, the intellect; and it excites no affection between those who practise it …

We can break down Screwtape’s definition like so:

- Flippancy is cheap and easy humor.

- You don’t even need to make the actual joke; just allude to one being made.

- Nothing is truly serious.

- Everything is ridiculous.

- Flippancy does not challenge your mind; in fact, it can make you stupid.

- Flippancy doesn’t make you joyful; it makes you a dulled, cynical snark.

Flippancy surrounds our stories and culture

I couldn’t help but consider Screwtape’s unabashed ode to flippancy while watching my (alas) least-favorite super-film of this past year, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.1

Like many of you, I’m a fan of the original Guardians of the Galaxy (2014). It’s truly inventive and irreverent. Director James Gunn and company included trace amounts of flippancy. But most of its humor came in other forms, including joy, fun, and The Joke Proper—and most such overt jokes were based in the characters’ unique natures.

Unfortunately, Vol. 2 dispensed with this character-driven humor—such as Drax’s failure to grasp metaphors—with interchangeable and flippant “jokes” any character could tell. Nothing was even partly serious, not even death or injury.

And to my memory, in many cases, the jokes weren’t even made. Only alluded to.

Male nipples. Ha ha! Space god needs to “go take a whizz.” Ha ha!

Oh, and surprise actual cameo by David Hasselhoff. Ha! Ha!

Literally, at that moment I felt the Guardians jig was up. They didn’t even do much funny with Hasselhoff. He just shows up to serve as the “joke’s” butt (butt! ha ha!) and that’s it.

Similar moments scourge Thor: Ragnarok. But I laughed more often anyway, partly because most of the humorous moments serve as overt yet affectionate genre parody, and are based on the characters. In other words, it’s not just any character making a “funny” poop “joke.” Rather, the comic moments are based squarely on who the person is.

Often the Marvel films are criticized for this kind of flippant humor. I think the criticism is usually undeserved; Marvel films offer more varied kinds of comedy than mere flippancy.

But unfortunately, people are not careful like Screwtape to distinguish between playful “fun” and dull flippancy. They’ll call the Marvel films “fun,” and then fault the DC films for their more serious tone (at least until the less-serious entry Justice League).

This is partly why I often defend the DC films: because despite their flaws, at least they consciously avoid flippancy. Other than in Suicide Squad, the films’ characters don’t often crack a quip or suffer a pratfall that undermines the dramatic weight of the moment or dialogue seconds ago. In other words, even these fantastical figures such as Superman and Wonder Woman act like real people, caught in the midst of a fearful or tense situation.

In response, critics call these films (with the exception of Wonder Woman) “cynical” and “over-serious.” They fail to consider that real seriousness and cynicism can’t go together. In fact, the true cynical critic is one who sees an attempting-serious story and assumes that, because it does not pause to be Self-Aware or silly, the story isn’t worth much.2

Superhero movies (and their critics) provide just one example.

Flippancy can appear frequently in our fantasy stories and broader popular culture.

For example, we often expect buzz-concepts like “self-aware” and “deconstruction” to apply to fantasy stories. It’s as if we believe these stories’ only value is not by repeating old myths in new ways, but simply tearing them down and showing how our cynicism is superior. This approach can make stories worse than “mindless entertainment.” Without balance, this approach renders these stories actively mind-harming: deadening, not sharpening, the intellect, and exciting no lasting affection for the story itself, or for our real neighbors.

In turn, this cynical, flippant approach to stories and popular culture infects reality. This year alone, we’ve seen how flippancy about sex and harassment has gone unchecked for too long, leading to our often-willful ignorance of creative men in power who abuse others. Even more often, we see people being flippant about serious matters, including personal character and even simple human biology.

Seriousness, which can include joy/fun, often has a job to do, a truth to explore, or a beauty to reflect.

But flippancy can never stop asking, “Why so serious?”

Next, I’ll explore why flippancy harms stories and ourselves. Then I’ll turn to the real example of a walk-thru Christmas pageant that shows our cure for flippancy: what C. S. Lewis called “a kind of happiness and wonder that makes you serious [and] is too good to waste on jokes.”

- In my review of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 for Christianity Today’s website, I touched on some of these themes. However, I would not say that I thought the movie was “rotten”; I’d only say that it dismissed even the lingering dramatic weight of the original film and decided to go full-on flippant. If that’s your thing, great. It’s just not my thing. Alas, the review-aggregating Rotten Tomatoes website interpreted my review as a simplistic “rotten.” Such interpretations, without the critic’s input, form the flawed Tomatoes critic “meter.” ↩

- Many fans may not understand that professional critics don’t see superhero stories in the same way they do. This doesn’t mean we should go all “populist” and claim that critics are elitist snobs, or reject their professional opinions on movies. But this also doesn’t mean that we feel compelled to accept the critical majority view of a movie—or else the simplistic appearance as such, as the Rotten Tomatoes “fresh/rotten” aggregations claim to show us. ↩

Excellent analysis. I especially appreciate this article because it clarifies my feelings about _The Orville_. I enjoy that show, but it’s humor often strikes me the wrong way. Now I have the word to explain why: it’s flippant.

A great article. Lots to think about here. Thank you.

I would agree that flippancy can be a problem, but I disagree that it was as much of a problem with Guardians 2 as this article makes it seem.

The brief Hasselhoff cameo didn’t come out of nowhere, it was set up earlier and based on Quill’s childhood fantasy of the Knight Rider character as his father.

Death and injury weren’t taken seriously in the movie? I can think of the conflict and only partial resolution between Gamora and Nebula, a conflict based on their past hurts; the part where Yondu tells Rocket he’s not the only one with a past full of hurts; and the part where Yondu acts more like a father to Quill than Ego does.

I would agree that not every moment was intended to be flippant. But apart from one character’s death, the prospect of actual threat to our heroes simply did not seem authentic. Where I lost it was when Drax was dragged behind their spaceship, battered and smashed, and simply falls to the ground laughing. At that point the jig was up and I didn’t “believe” (even for the bluff required of any story when you know all will survive) he could be injured.

In fairness, it’s likely audiences’ reactions to movies that are driving this kind of flippancy. I continue to defend the Marvel movies against critics who praise these stories as if they’re mainly made up of “fun” that is self-aware and un-serious. I’ve even begun to wonder if critics like these movies — that is, superhero movies — for reasons different from their serious fans. The critics seem to appreciate when they feel a movie is “self-aware” and kidding itself, with actors constantly winking to the screen that they’re in on the joke. But I’m not sure that’s what the fans want or why they like the films. Here, the main problem would be if the filmmakers decided that’s what the fans do want, and then they go full Batman and Robin on us.