Speculative Stories, The Eclipse, And Other Rare Space Phenomena

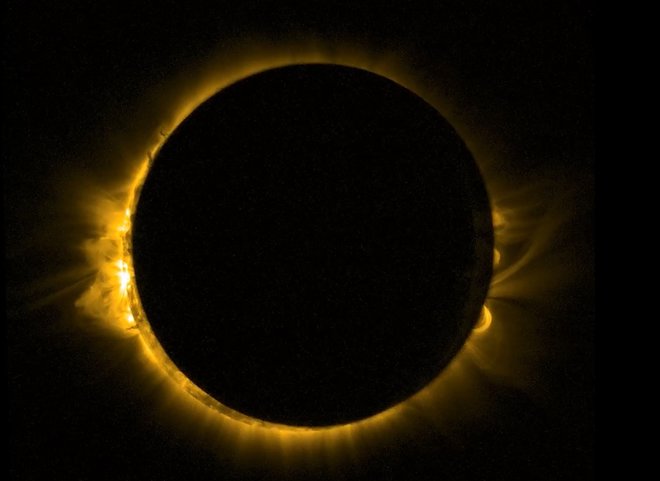

Last week here in North America we had the opportunity to observe a rare phenomenon in space—a total eclipse of the sun, at least in some places. In fact, in portions of approximately ten states. The solar eclipse event occurs when the moon passes between the earth and the sun and as a result, casts its shadow on the earth.

What I find interesting is that this kind of unusual space event does not find its way into more stories, either science fiction or fantasy. Or, sure, Star Trek and its various iterations had plenty of worm holes and nebula and star clusters and quantum singularities. I mean, their mission was to explore strange new worlds and to seek our new life, so space needed to have interesting things and places for them to explore. The rare space phenomena were woven into the fabric of the stores, and consequently “rare” wasn’t so very rare.

But what about other stories, not dependent upon the odd or occasional space event as part of the setting and/or the conflict? How many stories capitalize on the appearance of a Halley’s Comet, for instance? Or something as “scientifically impossible” as the sun standing still for a day?

But what about other stories, not dependent upon the odd or occasional space event as part of the setting and/or the conflict? How many stories capitalize on the appearance of a Halley’s Comet, for instance? Or something as “scientifically impossible” as the sun standing still for a day?

Or sure, there are the end-of-the-earth stories that have a comet colliding with earth, but I’m thinking about fantasy worlds that have some space phenomenon as part of the setting or a significant plot point.

I wonder if their rarity might be because such events would seem to take the reader beyond the realm of believability and smack more of the dreaded deus ex machina—an unexpected power or event seen as a contrived plot point.

Of course a skilled writer could properly foreshadow such an event, but still these kinds of natural and powerful events are out of the control of the characters in the story, and therefore may not contribute to the struggle and the overcoming which the protagonist needs to be a part of.

But other aspects of nature have long served as obstacles to a hero succeeding in his quest. So why not sudden darkness? Or a meteor shower? Or sun flares? Or the “Northern Lights”? Again, I’m aware that science fiction might be doing more of this than I’m aware of, but I am thinking about fantasy worlds, places that people create which seem strangely void of any unusual space activity.

But other aspects of nature have long served as obstacles to a hero succeeding in his quest. So why not sudden darkness? Or a meteor shower? Or sun flares? Or the “Northern Lights”? Again, I’m aware that science fiction might be doing more of this than I’m aware of, but I am thinking about fantasy worlds, places that people create which seem strangely void of any unusual space activity.

Sure, there are stories set on worlds that have two moons, but is there ever an eclipse of one? How does that effect the world? The people and animals in the world?

Because here in our world, reports came in that the total solar eclipse last week had some odd effects. Not unexpected, but sill, the event did not happen in a vacuum. And I’m thinking that fantasy worlds also ought not exist in a vacuum in which space has no oddities or occasional happenings.

But perhaps there are more stories out there that use space and I’m simply not aware of them. Do you have any in mind that I’m overlooking? Have you written a story that uses an event in space as something critical to the story? How do your characters understand space phenomena—as something that is the natural part of the world or as something God orchestrated to enhance or foil the hero in his quest? Should space happening become a greater part of stories, even fantasy stories?

Who was this person? He looked familiar, and as far as you knew, he supports good causes.

Who was this person? He looked familiar, and as far as you knew, he supports good causes. Now, what he says is technically correct. Many Christians are ignoring the lust-inducing moments of Game of Thrones, which by all accurate accounts feature blatant nudity and graphic scenes of sex and even rape. (Even non-Christians condemn the series for these moments.) Moreover, these scenes donât only endanger Christian viewers, who are called to purity and to shun any lust whatsoever. These scenes also endanger

Now, what he says is technically correct. Many Christians are ignoring the lust-inducing moments of Game of Thrones, which by all accurate accounts feature blatant nudity and graphic scenes of sex and even rape. (Even non-Christians condemn the series for these moments.) Moreover, these scenes donât only endanger Christian viewers, who are called to purity and to shun any lust whatsoever. These scenes also endanger

Now, a mere fifteen years later, things are different. Radically different. That editor I mentioned who said his house would never publish fantasy? He’s acquired at least two fantasy authors that I know about. In addition, Amazon. Now there’s an outlet for self-published books that did not exist before. And e-books. Publishing no longer requires a company; e-readers have made stories by anyone available to the public.

Now, a mere fifteen years later, things are different. Radically different. That editor I mentioned who said his house would never publish fantasy? He’s acquired at least two fantasy authors that I know about. In addition, Amazon. Now there’s an outlet for self-published books that did not exist before. And e-books. Publishing no longer requires a company; e-readers have made stories by anyone available to the public. But things have changed!

But things have changed!

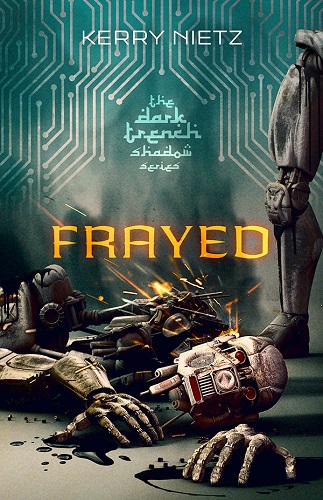

Kerry Nietz is a refugee of the software industry. He spent more than a decade of his life flipping bits, first as one of the principal developers of the database product FoxPro for the now mythical Fox Software, and then as one of Bill Gates’s minions at Microsoft. He is a husband, a father, a technophile and a movie buff. He is the author of several award-winning novels, including A Star Curiously Singing, Freeheads, and Amish Vampires in Space. You can follow Kerry at his

Kerry Nietz is a refugee of the software industry. He spent more than a decade of his life flipping bits, first as one of the principal developers of the database product FoxPro for the now mythical Fox Software, and then as one of Bill Gates’s minions at Microsoft. He is a husband, a father, a technophile and a movie buff. He is the author of several award-winning novels, including A Star Curiously Singing, Freeheads, and Amish Vampires in Space. You can follow Kerry at his

Rebecca

Rebecca