The Travisâ are back with another installment of our regular series on Warfare. Weâve been analyzing a writerâs perspective on calculating the cost of war, developing some tools and thumbrules you might start with when calculating the cost of war in your story, and seeing how this mundane task can yield helpful ideas for your writing. At the very least, your effort to make your warfare come across as thoughtful and realistic (by your story worldâs gauge of consistency) will be appreciated by the discerning uber-fans your serving.Â

Travis C here. Last time we left off with a detailed approach to calculating how much food both human and non-human fighters might consume and began a illustration using those calculations to gauge the financial impact of war in a fictional world. Our purpose wasnât to delve into all possible fine details, but to give you an example where doing a bit of math can provide some values for you to work from.

This week weâre going to dive into another significant expenditure of the army: pay. Travis P early in our series described different martial cultures and types of soldier through history. We also discussed some of the reasons a nation and a soldier might go to war. To begin this post, letâs list some of the reasons a warrior might be in the army and heading off to combat:

- Obligatory service enforced by cultural norms (drafts and conscription)

- Obligatory service enforced by negative consequences (slave soldiers, indentured servants, the draft)

- Voluntary service driven by internal resolutions (national pride, personal convictions)

- Voluntary service driven by external benefits (both immediate and long-term, promptly realized or speculative)

In the cases of obligatory service, the benefits of being in service might be woefully small, but itâs an obligation that must be served out regardless. As the executor of such a system, I either need a big enough consequence to ensure fear keeps the soldiers going and not deserting, or I need sufficient positive reward to keep them from turning against or away from the system of service. Recent historical examples include American emotions surrounding the drafts during World War II versus Vietnam, and nations that still practice mandatory conscription (for instance, Norway).

In the cases of voluntary service, we can expect some degree of difference between those driven by altruistic feelings, and maybe wanting/needing less compensation for their time and effort, as opposed to those in it for the cheddar. I posit that it is highly unlikely, and therefore needs to be justified to the reader, for a person to serve with no expectation of any reward or remuneration of any kind. At a minimum, the expectation of basic needs being met should be presumed. Because there are opportunities elsewhere the soldier could be pursuing.

Keep that in mind as we discuss historical cases and speculative examples. In most situations thereâs an opportunity cost at work–if those soldiers werenât going off to war, they could be doing something else. Maybe working in a different job, earning more (or less), enjoying their individual freedoms (or not), and living a satisfied and whole life with harmonious relationships (clearly âor notâ). The reward and compensation system you put in place needs to withstand your readers’ scrutiny and meet that basic test, or at least acknowledge why it works contrary to our experiences.

Before we looks at the wavetops of historical examples, letâs outline three basic characteristics of a military pay system:

- It must be sufficient

- It must be consistent and/or assured

- It must be in a useful form

Sufficiency was described earlier. There will also be problems if that pay doesnât come with some regularity or at least with assurance some form of compensation will be provided. And the pay must be useful. If you told me I wouldnât receive my regular salary in the currency of U.S. dollars but instead would receive it all in the latest digital currency (LoreCoins? BitHavens?) I would likely have something to say about that. Thatâs been true of every economy over time and should hold true in our fictional worlds. If the soldiers arenât paid enough, regularly, with something that holds value to them, there will be problems. They will desert, or loot, or steal from one another, or find some way to make it work out that will likely cause further challenges. (For example, the army that fought under George Washington during the American Revolution had continual problems with deserters because soldiers were paid with paper currency that did not have the value that precious metal coins had during that period.)

Biblical Armies & Plunder

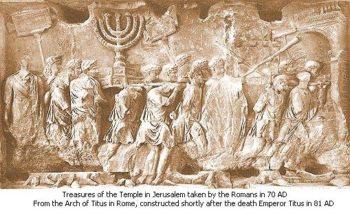

Travis P described various historical soldiers through primitive times. To capture one snapshot of the period leading into the more organized Greek and Roman forces, I want to pull examples from the Bible. The forces of the Israelite tribes, especially early on, existed as a militia-type force, drawn from the men, age 20 to about 50, of the tribe and operating together when the collective Israelite interests were aligned, such as against an invading kingdom. Over time, through the judges and later the kings, we see Israel form a standing army through the kingâs guard and develop tribal regiments that rotated duty through the kingdom. The Bible does not specify pay for those performing this duty. Those serving were expected to provide their own equipment and supplies. There was precedent for the nation to support their military forces through the giving of supplies in exchange for protection, as we learn in 1 Samuel 25. What also existed was the expectation of war booty.

The practice of looting, pillaging, sacking, plundering, and despoiling was common long before the Bible was written (and continued long afterward). By comparison with many contemporaries, the Israelites were relatively mild. Other than in the case of Joshua’s initial conquest of Canaan, Israelite forces normally:

- A besieged town would be given terms. If accepted, the town might be put to forced labor, but not enslaved or killed and the Israelites would occupy it.

- If the city rejected the terms and the Israelites won the ensuing siege/battles, the men might be put to death, but the women and children would be taken as spoils and divided.

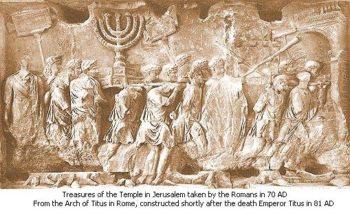

The spoils that came from victory would be distributed among the Israelite militia, including shares for those who stayed behind to guard encampments. Rewards trickled down from the top with officers receiving special shares, often for acts of heroism and might. Lastly, while one-time spoils from a city could be distributed among the soldiers, it was not uncommon for occupied cities to pay annual taxes or indemnities to the victors, providing another source of national income. These expectations existed across many cultures at that time, including the Hittites, Egyptians, Assyrians, and later the Persians.

It feels uncomfortable to write about the spoils of war, but that was a reality of conflict and in some ongoing wars (particularly among poorer nations) is a reality up to present times. What Travis P called “barbarian” armies in fact fought primarily for plunder, all of their pay stemming from what they took from conquered enemies. Even as paid professional soldiers were incorporated into various nations’ defenses, the basic pay of warriors for a long time only marginally sufficient to meet their basic needs. Higher wages could be earned in many different non-military occupations, so the aspiration for gaining wealth through spoils was very real and necessary tool to maintain an army.

Roman Era

Rome represents an organized military example with a systematized method of compensating soldiers at different levels. According to Whiston, we see the rise of regular pay around 405 BC with a stipendium (from stipem and pendo since copper by weight was the common coin before silver was minted) for soldiers paid out from the Roman general tax (tributum) about three times per year. At times Rome also provided pensions for those who completed careers in military service, called a praemia militare after 20 years of service (this number grew through Romeâs history to 25 years or more of mandatory service). These pensions sometimes included lands, working animals, roles in local governance, and exemption from certain taxes. Steve Wills has a lot of great connections between this system, how it eventually fell apart, and the role of pensions in modern militaries.

Spoils remain a significant motivating factor for those serving in the Roman army. Striping the dead of their valuables was common. The hope of riches was a useful tool for recruiting the next generation of legionnaires, and certainly commanders could be expected to inflate the likelihood of gaining such wealth in order to draw more candidates into the ranks. Though in general, Roman soldiers primarily lived off their salaries.

Spoils remain a significant motivating factor for those serving in the Roman army. Striping the dead of their valuables was common. The hope of riches was a useful tool for recruiting the next generation of legionnaires, and certainly commanders could be expected to inflate the likelihood of gaining such wealth in order to draw more candidates into the ranks. Though in general, Roman soldiers primarily lived off their salaries.

Lastly, some sources indicate portions of a Roman soldiers pay came in the form of salt (and to be fair, itâs also commonly considered a myth). Coinage was expensive to produce and may have represented a hurdle to use in more common low-price purchases, salt would have represented a valuable commodity that could be exchanged for other goods. Hence our connection to any form of military compensation: it must be useful.

Middle Ages & Feudalism (and the Crusades)

Since many fantasy story worlds share medieval roots, itâs appropriate to look at this period for examples of military pay systems. We donât have space to unpack all of feudal society and the variations of society that existed across this period right now. In fact, many parts of the world that interacted with one another during this time operated under different socio-economic systems. Feudal obligations were discussed in our earlier post covering knights. I do want to dive into a few specific elements of this system. If you are looking for something with more depth (especially for specific definitions), this is one great resource to help authors out.

Across our medieval countryside we have various divisions of land (hides, leets, hundreds, yokes, sulongs, etc.) that were worked by folks of varying social levels. Yeomen, who were freemen, were men-at-arms that held land (often 60-120 acres) in return for their military service. Yeomen would likely be vassals to a noble lord or knight, holding their land as fiefs and submitting to certain obligations to include their military service and financial aids. Working up the social ladder, lords would pay their respective obligations all the way up to their king. Knights could come from the noble ranks above yeomen and hold their lands as knightâs fee for their service or as a reward for exceptional service after rising as a commoner.

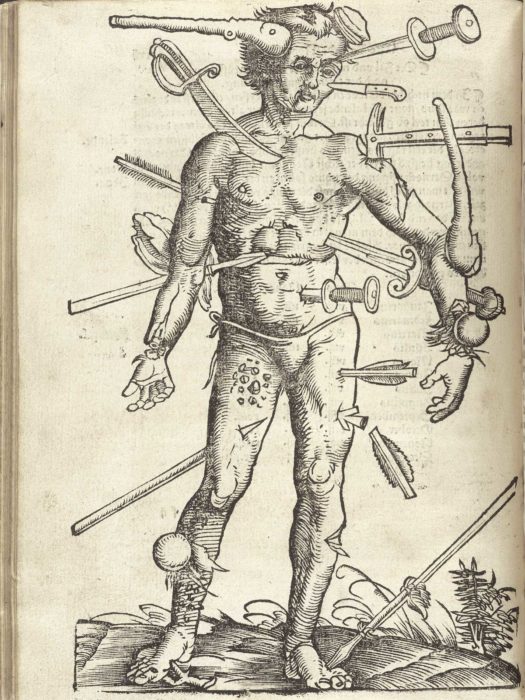

When a lord called upon his vassals for military service, it typically involved specific terms and conditions. Due to the agrarian culture, military campaigns tended to happen between planting season and harvest (which was also true for most but not all ancient armies–the Assyrians pioneered fighting year-round, as the Romans also did), and fighting seasons certainly dictated many obligations. Traditionally this consisted of 40 days per year for martial duties due to oneâs lord. Feudal maintenance was the money payment made to those soldiers fighting for their lordâs interests executing such duty. And letâs not forget the reality that such small wages could be (were expected to be) supplemented with booty. From one of my favorite period pieces:

Image credit: Project Gutenberg

[Asked to Samkin Aylward, Archer & Recruiter]

âAnd where got you all these pretty things?â asked Hordle John, pointing at the heap [of loot] in the corner.

âWhere there is as much more waiting for any brave lad to pick it up. Where a good man can always earn a good wage, and where he need look upon no man as his paymaster, but just reach his hand out and help himself. Aye, it is a goodly and a proper life. And here I drink to mine old comrades, and the saints be with them! Arouse all together, mes enfants, under pain of my displeasure. To Sir Claude Latour and the White Company!â

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The White Company

As the period progressed the system changed to relieve many vassals of their military obligations via scutage, or the payment in kind for military service. For a prosperous fief it would make sense to pay money or goods to meet their obligations rather than provide service in the field. Another unique form of taxation for military purposes was feudal aid. These existed as one-time financial duties paid from vassals to their lords as part of their feudal obligations. Four common milestones included the knighting of the lordâs eldest son, the marriage of his eldest daughter, ransom in case of capture, and when called upon to support a lord during a specific campaign like a crusade. Â Â

The Crusades are a good place to end our Middle Ages discussion. The perceived spiritual rewards of joining a crusade were substantial enough to draw many participants. Early crusade planners like Pope Urban II recognized that financing such ventures would be critical: âIf the money be not wanting, the men will not be wanting.â Individual crusaders had to pay their own way, and many sold their lands, goods, inheritances, or financed their participation via loans and with gifts from their families and friends in order to participate. Why would a soldier put themselves under such obligations? Certainly the promise of heavenly rewards was strong, but the reasonable expectation of temporal reward in the form of prizes and new lands was a powerful motivating force. If you are interested in an easily read reference on such matters, I highly recommend this resource from the University of Wisconsin by Zacour & Hazard.

Transition From Feudal to Modern Militaries

Looking at the periods after the Middle Ages up into the 19th century (when many of our modern military pay structures were maturing), we see a transition to consistent pay with reduced reliance on plunder. Ashore, the armies of Europe transitioned from service as part of feudal obligations toward a more formal pay system executed by central governments. Using the British Empire as an example, soldiers had clear gradations in pay based on rank like we see today. Varying levels of skill and perceived risk impacted take-home pay as well; the drummer and trumpeter in the foreranks might actually receive more than a common foot soldier, and neither as much as a dragoon or standard cavalry. Recruiting efforts were creatively designed to draw in those in need with the promises of regular pay and recruiting incentives, starting with the Kingâs Shilling.

Credit: redcoat.org

“If any gentlemen soldiers, or others, have a mind to serve Her Majesty, and pull down the French king; if any prentices have severe masters, any children have unnatural parents; if any servants have too little wages, or any husband too much wife; let them repair to the noble Sergeant Kite, at the Sign of the Raven, in this good town of Shrewsbury, and they shall receive present relief and entertainment.â

From the play The Recruiting Officer, by George Farquhar

Soldiers were expected to pay for certain portions of their kit from their wages. While basic rations might be supplied through the quartermaster, the cost for additional supplements like beer may have been borne by individuals. For those in the cavalry, this could include the feed and forage for their horses. Officers were expected to provide their own uniforms and generally provided for themselves in most respects. An officerâs appearance was truly a reflection of their financial state. Some nations also practiced the purchase of commissions as a means of generating national income (limited) and helping to assure loyalty to the nation they served. Such an economic decision would be weighed against the likelihood of receiving a positive return on the investment through social influence, prizes, ransoms, or other compensation. Â

Pay was certainly a strong influence on the sailors of the day. Volunteers for sea duty were often scarce and âThe Evil Necessityâ of impressment, that is, capturing crews of other ships and forcing them to sail for your military, was used to crew military vessels of the British Navy (among others). While individual wages were generally low (and not adjusted for inflation from 1653 through about 1797!), crews could be eligible for prize money based on participation in successful combat. Like all things, it trickled down from those of higher rank taking the lion’s share, but contributed a not insubstantial amount of a sailorâs compensation.

Credit: Painting by Robert Dodd, Royal Museums Greenwich

How could nations during this post-medieval period afford such militaries? To some degree, it was access to capital, growth of centralized governments, and expanding their reach into new markets and gaining access to previously unrealized resources. In a circular argument, the need for greater resources required the use of military power to conquer and then hold those colonies against internal and external threats. Hence you end up in situations like the British paying Hessian forces to serve in the Americas, and the American upstart government offering lucrative terms for Hessians to defect (I mean, I donât know what Iâd say to farmland, two pigs, a cow, and citizenship? Sounds pretty good.)

The Modern Military Pay System

Most modern nations have implemented consistent pay systems for their military forces as a means of providing assured defense for their people. The United States and other industrialized nations have systems that generally follow these practices:

- Pay and allowances are based off of some combination of rank, seniority, time-in-service, with a differentiation between officer and enlisted service.

- Certain allowances may be treated more favorably for a soldier than a civilian (e.g., some portions of military pay are tax-free).

- Pay is issued with regularity and predictability. Honestly though, ask a service member for a good pay story and they will certainly have some example where âthe systemâ caused challenges due to delays, overpayments, underpayments, recoupments, etc. There is a lesser degree of uncertainty today than weâll see in past generations.

- Generally, there are no financial incentives for military performance other than through structured promotions in rank. You wonât see a general receive a cash award for how well they executed a campaign. You might correlate a major rising to lieutenant colonel a little faster because of her performance and therefore receiving that pay raise earlier than her peers.

- Pay is issued in the currency of the nation.

- There are often other tangible and intangible benefits that are used to promote volunteering for service. Tangible benefits such as healthcare, education opportunities, housing, training, and retirement pensions continue to be used across services and nations as a way of attracting talent. Intangible benefits such as the sense of camaraderie, service to a greater mission, and national/collective defense wax and wane with circumstances, but each generation has had something to point towards as an internal positive benefit of service.

- Taking loot is actually forbidden and is in some cases a crime under military law.

To some degree, modern military pay systems operate against internal competition with non-military employment opportunities. In order to attract and retain talented people, the military must offer compensation that reflects a similar opportunity for the person serving. Otherwise, at some rate, fast or slow, people would migrate away from service into other roles in society and fewer would join the ranks to replenish them. One current challenge the U.S military faces is attracting and, more so, retaining those with significant information technology (IT) skillsets. The civilian market for such talent is strong and aggressive, with many perceived benefits the military cannot guarantee. Why maintain a computer system while deployed far away for long periods when you can maintain such systems here and go home at night? Military leadership has been forced to consider new ways to compensate those technology specialists it gains and trains to avoid shortfalls in those unique capabilities.

Looking into the recent past of the United States, both the Union and Confederate forces come across as having military pay systems similar to today. As this source suggests, the regularity was likely much different as quarter and paymasters had to catch up with moving military units, causing delays in payment. The pay period of every two months is also shocking to our modern expectations. We see a differentiation between enlisted and officer ranks, some disparity between the two forces, and a significant reliance on variable allowances for rations, forage, and fuel, along with support for horses and attendants. We also see the disparity between ethnic backgrounds when it came to pay.

The Future: Where Are We Heading?

We can certainly look around and see the future unfolding. Pure digital currencies? A return to standard-backed currencies based on other rare (or limited) resources? Either of those may come to pass and factor into how an organization (nation-state or otherwise) might choose to compensate those who serve. Stories like Avatar suggest access to advanced technologies (like medical treatments) might motivate individuals to provide martial services when such capabilities are beyond the reach of the masses. Avatar also provides an interesting viewpoint on the role of private security forces that are effectively self-contained armies used for corporate, non-governmental purposes. To some degree the future is here with the increased presence of paid professional security forces (i.e., contractors) in modern conflicts.

Credit: Vignette Wikia

Lady Katie Illustration Part II: Paying for an Army in the Field

We left off with our illustration as the Lady Katie needs to fund 2200 archers, 3300 foot soldiers, of which 1000 are mercenaries drawn from other lands, 400 knights and their attendants, 12 war wolves, and a dragon. All to stand up a field army to fight against her neighbor, the Mad King Crabcakes of Old Seaside, who threatens invasion. We made some simple assumptions and determined her cost for food for a six month campaign would run nearly ÂŁ19,605 which we pegged to the value of the pound around 1400 A.D. and representing nearly 2/3 of her demensesâ annual income.

My first reference will be to payments of wages during Edward IIIâs reign and the Hundred Year War. My favorite fictional knight, Sir Nigel Loring, served on campaign during this period, and his contemporary the Earl of Salisbury was paid:

- ÂŁ933 for services rendered over three months

- ÂŁ2003 for his wages, 23 knights, 106 men-at-arms, 30 mounted archers, 50 Welsh footmen, and 63 sailors aboard ship.

- ÂŁ38 for siege engines and other works

- ÂŁ37 for sundries

- ÂŁ155 for the loss of 8 horses

That gives me a ballpark figure when thinking about subcommanders and their smaller units. But it doesnât help me differentiate between the types of soldiers and their expected pay levels. I found some helpful information that did break down, by day and by role, some common pays:

- Foot Archer: 2-3d/day

- Mounted Archer: 6d/day

- Knights: 2s/day

- Cavalry: 18d/day

- Infantry: 2-8d/day (2d/day for foreign soldiers) depending on rank

Using our earlier estimates of personnel, that gave me a figure near ÂŁ32000. Thatâs about the annual royal incomes from Edward IIIâs period and for Lady Katie will represent a huge obligation to meet. That doesnât count for paying off her dragon or the war wolves. So where does that leave us as the author?

- I need to consider a reason why the dragon would serve in her army. Gold? Jewels? Avoid being hunted? Probably getting a bunch of cows as food will be insufficient to satisfy her during the six month campaign. I need to really dig into a dragonâs motivations for aligning with a human-centric cause.

- Mostly because Iâm cheeky, I think the war wolves will demand payment in salt. What use would they have, being sapient mammals, with coins? They can trade the salt with foresters in exchange for venison jerky to last them through winter. Similar to the dragon question, we need to think through a legitimate compensation for this non-human entity in the story.

- Lady Katie will need to determine what military obligations sheâs willing to take in the form of scutage. If some of her baronesses have lucrative economic situations, itâs likely they may balk at providing people for military service. Rather than fight an internal battle at home and against them, Lady Katie may concede to receives funds in exchange.

- If she receives funds in exchange for service, she still needs to find sufficient soldiers to fill the ranks. If not filled via feudal obligation, are there enough fighting men and women inside her realm to serve as freefolk? Or will she need more than her 1000 mercenaries?

- Maybe Lady Katie has been in this place before and demonstrated she canât meet her financial obligations to her troops, and thereâs a strong current of distrust among her subjects. Once they hear the tax collector coming around and word of feudal aid being taken up, they will react.

- Maybe itâs not Lady Katie who is the concern, but her own leaders who have taken advantage of their roles distributing pay in previous campaigns. If corruption is rampant in the paymasters and noble leadership, how will the fighting forces react? We saw this in Braveheart as the Scots recognized their leadership would parly for new lands and titles while commoners would likely see nothing.

- If Lady Katie canât come up with sufficient funds from her coffers, where will she get them? Loans from other nations? Loans from banks? Taxes? The expectation of gaining new lands when she marches into Old Seaside and attacks King Crabcakes? I think, as we noted earlier, she needs to manage expectations as far as looting goes. Maybe sheâs altruistic and wants to prevent looting, so she promises extravagant wages and will set up strict discipline again such actions; she knows innocent people will suffer due to her army crossing lands (friendly and foe) and seeks to prevent negative reactions. Maybe she decides this is all Old Seasideâs fault and they deserve to be plundered for making her have to go to war. Maybe she decides to blindly not ask questions of what her soldiers will do. In any case, there are clearly some plot points to be developed from her decision.

Conclusion

Any of those factors could provide a seed for tension in the story. They also represent opportunities for authors to use mundane topics like figuring out the pay schedule as vehicles for deeper characterization.

We hit several historical wavetops, but hopefully gave you a starting point to explore further how various pay structures impacted the militaries of nations through time. The reliance on plunder to supplement no wages, followed by limited sustenance-only wages, ultimately shifted toward a regular salary comparable to many related professional fields.

As writers of speculative fiction coming from the faith, we have guidance concerning not only military compensation, but pay in general. God provides us His perspective on wages in a few places, but his command in Deuteronomy 24:14-15 says it well:

Do not oppress a hired hand who is poor and needy, whether he is a brother or a foreigner residing in one of your towns. You are to pay his wages each day before sunset, because he is poor and depends on them. Otherwise he may cry out to the Lord against you, and you will be guilty of sin.

And in the later part of Matthew 10:10: âThe worker is worthy of his wages.â

We have a visceral reaction to cases where work is performed but inadequate wages are paid. Anytime you monkey with this equation, you should expect a consequence:

Effort x Time = Internal Reward + External Reward + Spiritual Reward

As an author you have all the power in your world to leverage that equation and drive the emotions of your characters, and therefore, your readers as well.

Many fruitful, if unhappy, avenues of discussion might be opened, not least how parents can so thoroughly fail to protect their children. Our normal focus on culture, however, leads us down another road. Michael Jackson is gone, but his music is still here. As we see with increasing clarity who Michael Jackson was and what he did, should we continue to listen to his songs?

Many fruitful, if unhappy, avenues of discussion might be opened, not least how parents can so thoroughly fail to protect their children. Our normal focus on culture, however, leads us down another road. Michael Jackson is gone, but his music is still here. As we see with increasing clarity who Michael Jackson was and what he did, should we continue to listen to his songs?

Another consideration some may bring up for writers is, for whom do you write? After all, when you want the general market to read your books, don’t we need to “fit in” so that secular readers will pick up our books?

Another consideration some may bring up for writers is, for whom do you write? After all, when you want the general market to read your books, don’t we need to “fit in” so that secular readers will pick up our books? The New Testament talks a lot about abiding in Christ, which doesn’t seem like a place for the naive. After all, “The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom.” I conclude that Christians will opt for the “prudent” option—that we should see evil and hide from it.

The New Testament talks a lot about abiding in Christ, which doesn’t seem like a place for the naive. After all, “The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom.” I conclude that Christians will opt for the “prudent” option—that we should see evil and hide from it.

I think “relevance-seeking” is an apt description of many Christians today, as if it’s up to us to make God and His word somehow germane or applicable or pertinent to society today. In truth, God’s word is already apropos to our lives and it doesn’t need our dressing it up or our covering it up so that “seekers” will feel more comfortable with our stories.

I think “relevance-seeking” is an apt description of many Christians today, as if it’s up to us to make God and His word somehow germane or applicable or pertinent to society today. In truth, God’s word is already apropos to our lives and it doesn’t need our dressing it up or our covering it up so that “seekers” will feel more comfortable with our stories. What McCracken seems to say, in agreement with Begbie, is that we need to walk the line between the fallen world and the reconciliation believers find in Jesus Christ. We cannot deny the fact that we were once dead in our transgressions. But at the same time, we ought not make our redemption, our new life in Christ, a mere footnote to the story.

What McCracken seems to say, in agreement with Begbie, is that we need to walk the line between the fallen world and the reconciliation believers find in Jesus Christ. We cannot deny the fact that we were once dead in our transgressions. But at the same time, we ought not make our redemption, our new life in Christ, a mere footnote to the story.

Spoils remain a significant motivating factor for those serving in the Roman army. Striping the dead of their valuables was common. The hope of riches was a useful tool for recruiting the next generation of legionnaires, and certainly commanders could be expected to inflate the likelihood of gaining such wealth in order to draw more candidates into the ranks. Though in general, Roman soldiers primarily lived off their salaries.

Spoils remain a significant motivating factor for those serving in the Roman army. Striping the dead of their valuables was common. The hope of riches was a useful tool for recruiting the next generation of legionnaires, and certainly commanders could be expected to inflate the likelihood of gaining such wealth in order to draw more candidates into the ranks. Though in general, Roman soldiers primarily lived off their salaries.