Great Art And Story

Years ago Cap Steward did a guest post for Spec Faith, not discussing art per se, entitled “Actually, Fantastic Films Donât Require Sex and Nudity.”

At one point he said

Itâs at least a possible sign of danger when we approach a controversial topic with appeals to a Higher Power that is not God. In this case [what is acceptable in fiction regarding sex and nudity], the needs of the story are trotted out in an effort to eliminate any objections, as if the discussion is over once the story has spoken.

Add to this the oft repeated accusation that Christians no longer produce art but “tracts,” and I begin to wonder, what’s so great, so necessary about producing art?

The thing is, “art” is a word with transient meaning. The definition of art in the Oxford American Dictionary is helpful, I think, in making this point clear:

the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power

“Beauty” we say, is in the eye of the beholder (though that may or may not be true), and certainly what moves one person to tears may or may not affect another person in the same way, so if art is human creativity appreciated for its beauty or emotional power, then it seems apparent that what one generation or culture reveres as art may not be revered universally.

Once, pictures of plump cherubs fluttering over figures with halos was considered great art. Hundreds of years later, paintings of common objects such as soup cans became cutting edge art—a sort of rebellion against the art of abstraction that focused on shape and shade with little thought of beauty or emotional power.

Once, pictures of plump cherubs fluttering over figures with halos was considered great art. Hundreds of years later, paintings of common objects such as soup cans became cutting edge art—a sort of rebellion against the art of abstraction that focused on shape and shade with little thought of beauty or emotional power.

And yet from Picasso to Monet to Warhol, from the Renaissance painters and the Greeks that inspired them to the Modern artists who rebelled against them, from the statue of David to Andres Serrano’s profane picture of his own urine, works of questionable beauty or emotional power have made their way into museums of art.

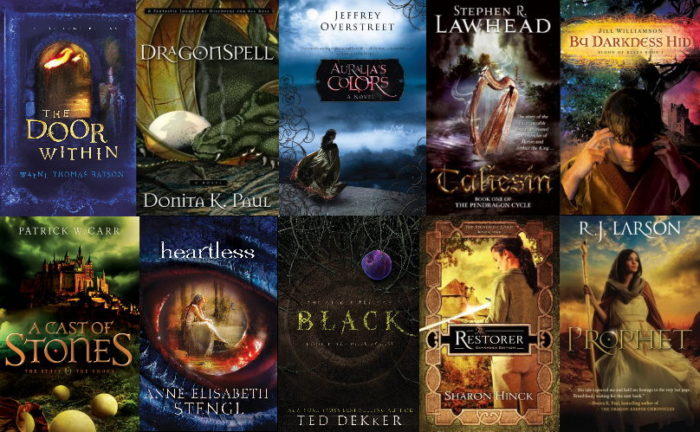

Now the cry goes up—where’s the great Christian art of today? Most people asking the question are referring to more than visual art.

In connection to stories, the implication is that “great art” must meet some acceptable standard which includes a degree of realism. I find this odd in the day of animation and computer-generated images. Why would Christians want their artists to revert to a former artistic style?

But greater than this question is the one that Cap Steward raised: should the demands of Story rise above the demands God places on His people?

Yes, demands. God’s grace is free. He recognizes we cannot earn salvation. We are incapable of what it takes—a pure life. Consequently He offers the pure life of His Son in our place, a substitution reminiscent of the various substitutions pictured in the Old Testament (such as God taking the Levites as His in place of the first born of all the people of Israel—see Numbers 8).

But once we come to God, He doesn’t turn us loose to do whatever we want. Rather, He lays out for us the path of discipleship. We are to follow Him in obedience.

So do the demands of Story ever conflict with the demands of obedience? I don’t doubt that some people would say, No—Story is about showing this world as it is, so there is no conflict because there is no question of obedience. A novelist, in essence, is simply holding up the camera and clicking.

Other people would argue, of course there is a conflict because the novelist can determine where to aim the camera—if toward sex, nudity, graphic violence, then obedience is very much in question.

The “where is Christian art” crowd claims that to make great art, the Christian must show the world as it is. Anything less is dishonest and a form of Kincaid-ism—painting with words only that which is beautiful, nostalgic, and evocative of warmth and security.

But that brings me back to the question: what’s so necessary about the Christian producing art? After all, the Great Commission is for Christ’s disciples to go and make more disciples, not great art.

Often people with a perspective like mine are chided for requiring a utilitarian function to what we create. We should do good art because God is glorified in good art, the thinking goes, and our purpose is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.

As it happens, Scripture doesn’t spell out this “glorify God and enjoy Him forever” purpose, though it certainly can be assumed from various passages. However, I’ve been taught that “the plain thing is the main thing” and that we aren’t to re-interpret clear Scripture based on more ambiguous passages.

It is clear that followers of Jesus are instructed to go and make disciples. It is also clear we are to walk in a manner worthy of God, of our calling, of the Lord (1 Thess. 2:12, Eph. 4:1, Col. 1:10). It is clear we are to be holy (1 Peter 1:15-16), that we are to take up our cross and follow Jesus (Matt. 16:24), that we are to love God above all else, then love our neighbors as ourselves (Luke 10:27). But make great art?

I understand, many will say, when we make a beautiful thing, we glorify God because He is the Creator who endowed us with the ability and our doing what He has gifted us to do proclaims His greatness, His glory, in the same way that the heavens proclaim who He is.

I don’t think I buy that explanation. God made the heavens. He didn’t make my story. He made me with the ability to make a story, and my ability to do so is a glory to His name, but that still doesn’t mean my story glorifies Him. Not my story, or any story.

Quite frankly, art is too ephemeral to be a great means of glorifying God. Today someone may praise a work as great art and tomorrow others will cast it into the remains bin or deleted from their iPad.

What’s more, God Himself seems to put more store in our relationship with Him and in how we treat others.

True, as many point out, God did go to great lengths to give Moses detailed blue prints for the tabernacle and all its furnishings, and even the priestly garments. He said more than once that these objects were created for beauty (e.g. Ex. 28:2). However, none was exclusively for that purpose. The lamp, the incense altar, the table for the bread of presence, the ark, the priestly garments, all had a function in the worship process.

True, as many point out, God did go to great lengths to give Moses detailed blue prints for the tabernacle and all its furnishings, and even the priestly garments. He said more than once that these objects were created for beauty (e.g. Ex. 28:2). However, none was exclusively for that purpose. The lamp, the incense altar, the table for the bread of presence, the ark, the priestly garments, all had a function in the worship process.

But back to fiction. If all this “great art” talk is missing the mark when it comes to what God tasks Christians to do, should we care about the quality of stories, or are we making artificial judgments that don’t need to be made and are better left alone?

I’m of the mindset that God cares about all we do, so we certainly ought to care. I think we should grasp the truth of Exodus and make our stories both functional and beautiful. To do that, we must also grapple with the demands of our culture when it comes to realism in Story and the greater demands of Scripture to obey God in all we do and say.

In the end, because fiction is first a form of communication, I think stories should pay attention to what Scripture says about our correspondence with one another. A good start might be this:

As a result, we are no longer to be children, tossed here and there by waves and carried about by every wind of doctrine, by the trickery of men, by craftiness in deceitful scheming; but speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in all aspects into Him who is the head, even Christ, from whom the whole body, being fitted and held together by what every joint supplies, according to the proper working of each individual part, causes the growth of the body for the building up of itself in love. (Eph. 4:14-16, emphasis added)

Above all, stories show, so in the Christian novelist’s “speaking” he is to show truth and to do so in love—love for his reader.

If novelists all wrote stories from that perspective, would they all look alike? Not at all. Would they be whitewashed? I don’t think so, though I think Christian stories would be distinct.

At the same time, if readers came to stories with that same perspective, I think they’d be a lot less concerned with what words offend them and more concerned about what truth the novelist is showing.

This article is a re-post of one that appeared her in September, 2014.

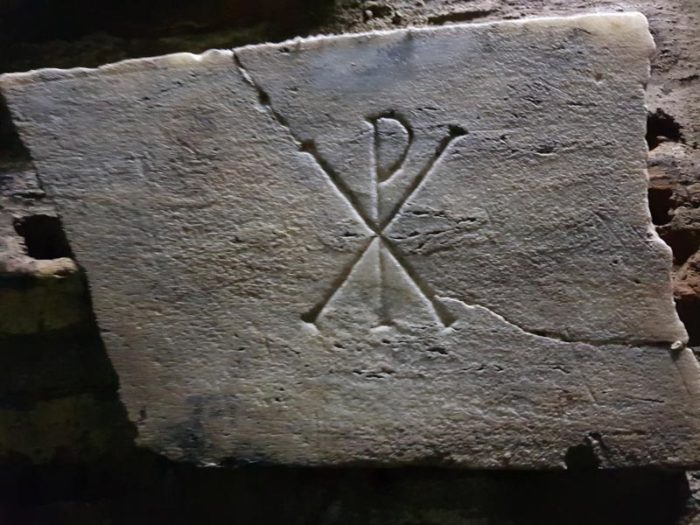

It’s not surprising. Humans must have art. Humans must especially have art in their sacred places. What is more notable is that the early Christians borrowed not only Rome’s art forms but, to a limited extent, its pagan imagery. The classic image of Orpheus taming the wild animals frequently appears in the Catacombs, doubtless as a type of Christ.

It’s not surprising. Humans must have art. Humans must especially have art in their sacred places. What is more notable is that the early Christians borrowed not only Rome’s art forms but, to a limited extent, its pagan imagery. The classic image of Orpheus taming the wild animals frequently appears in the Catacombs, doubtless as a type of Christ.

But in this day and age when myth is popular and superheroes are in TV programs, movies, and games, let alone, in books, I wonder if the skepticism we need to enjoy the mythological might not affect our understanding of the Bible. I mean, look at the amazing feats accomplished by the

But in this day and age when myth is popular and superheroes are in TV programs, movies, and games, let alone, in books, I wonder if the skepticism we need to enjoy the mythological might not affect our understanding of the Bible. I mean, look at the amazing feats accomplished by the  I realize that I’ve taken that same skepticism into the way I look at photos. There are pictures with colors so vibrant, I question if they are real or if the photographer/artist/creator has enhanced them to make them pop, to “improve” on the nature which they supposedly represent.

I realize that I’ve taken that same skepticism into the way I look at photos. There are pictures with colors so vibrant, I question if they are real or if the photographer/artist/creator has enhanced them to make them pop, to “improve” on the nature which they supposedly represent.

But I wonder if the movie industry isn’t squeezing itself needlessly. Seems to me there was a time not so long ago that quiet movies with smaller casts were quite possible. In 1968 a movie with an original screenplay became a $56 million success. I’m referring to Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner starring Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier, and Katharine Hepburn. Big stars at the time, so I’m guessing this was not a cheap movie.

But I wonder if the movie industry isn’t squeezing itself needlessly. Seems to me there was a time not so long ago that quiet movies with smaller casts were quite possible. In 1968 a movie with an original screenplay became a $56 million success. I’m referring to Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner starring Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier, and Katharine Hepburn. Big stars at the time, so I’m guessing this was not a cheap movie.