Years ago I wrote a personal blog post with the title: 7 Christian Objections to the Existence of Aliens–Posed and Answered. I created the post in response to certain Christians I knew who objected to placing aliens in science fiction. I felt their objections were not valid, but over time I’ve developed a more sympathetic view of what they were saying. So allow me expand on what I wrote about previously while presenting some objections to the use of aliens in science fiction, explain those objections, then suggest some methods of how to respond to them. I will include addressing how Christians might write about aliens differently than how secular writers do. Note that sometimes fantasy creatures function very much like aliens, so what this post addresses could also apply to the fantasy genre in some cases.

Most science fiction writers will be very familiar with the roots of the modern obsession with aliens, but for clarity’s sake, it’s worth mentioning here. The root idea is that the Planet Earth is not any place special. As US astronomer Carl Sagan put it, it’s just one of billions and billions of likely inhabited worlds, and since people with a wordview similar to Sagan would say that random forces of nature acting according to their own properties brought about life (I would disagree, but that’s what they’d say), then life is not special. If life isn’t special, it can be anywhere the conditions for it are right. And since it seems untold billions of worlds exist, there ought to be untold billions of aliens.

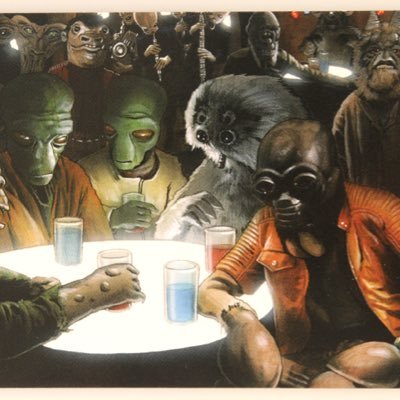

And since evolution is thought by scientific materialists like Carl Sagan to have generated life without any guiding purpose or plan, alien life ought to be quite exotic in comparison to human life. While some of the most famous brands of science fiction in visual format such as Star Trek have featured quite a few very human-looking aliens (which was largely done because of the need to put actors in costumes), Star Wars, the technology of which is in many ways less scientifically accurate than Star Trek, has done a lot more to show many exotic-looking aliens. Though it can be said that aliens with features and characteristics quite different from human beings is a standard feature of written science fiction. The main art of writing aliens as done from what we can call a “secular perspective” is to make them internally consistent and to show how evolution made them what they are in a way that fits their natural environment. And sometimes even fantasy stories are shaped by the same kind of thinking, in which fantasy creatures are developed with an eye to how they’d survive and evolve.

Aliens, some exotic, in Jabba’s palace.

Image copyright: Lucasflim

So while it’s entirely possible to make science fiction without aliens (or fantasy without fantastical creatures)–say, by doing cyberpunk, or time travel, or by creating a galaxy in which the only known intelligent life is human (as Isaac Asimov did in the Foundation series, even though he was a scientific materialist), among other means, most futuristic science fiction includes quite a lot of alien characters. And when looked at in context of those who believe that the Earth is not any special place and that life isn’t special, stories featuring aliens wind up being advertising (“propaganda” if we wanted to use a stronger word) for the notion that life is no miracle, that the Planet Earth is ordinary.

Christians, looking at a Bible in which the Planet Earth was important enough for God to care about it enough to send Jesus to Earth to die, naturally may object to fiction that makes it seem like “of course aliens are everywhere, because life has evolved everywhere.” As a result, it’s understandable that some Christians who write science fiction have chosen to exclude aliens from their tales and have raised objections to aliens as commonly portrayed. Though in fact the people who protest about aliens in science fiction the most are probably not science fiction readers at all, but are merely reacting to the way evolution is portrayed in sci-fi and don’t understand why any Christians would want to portray aliens at all.

But I think aliens can be a useful literary device and they are also in general a genre expectation for science fiction, just like fantastical creatures are an expectation for fantasy. So I want to write aliens, but to do so, I think it’s important to deal with the objections to aliens that Christian people have raised. As I answer these objections, I’ll also recommend employing aliens in a way that’s different from how “secular” writers show them, which I consider “opportunities” and which I’ll set off in bold so you can locate that section easily.

Objection 1: No aliens (or alien planets)Â are mentioned anywhere in the Bible, so there must not be any.

A counter-argument could be made based on the fact that the Bible certainly does mention non-human intelligences in the universe. The difference between supernatural intelligence and aliens is something I’ve discussed in a previous post (Angels and Aliens: Is There a Connection?), but nonetheless, the point could be made that the Bible clearly envisions intelligent beings other than the human race…though not really as aliens. (Still, there are some unique opportunities for portraying aliens that a Christian could adopt that relate to supernatural angels, such as portraying “alien angels,” something I discussed in the angels and aliens post.)

However, the best answer to this question would be to point out that the Bible didn’t mention the Americas either–yet North and South America existed and furthermore were inhabited by intelligent beings–humans of course, but to Europeans during the Age of Exploration it was a mystery how human beings had already arrived in this newly-discovered land. Christians eventually came to see no contradiction in noticing that the Americas were not mentioned in the Bible and existed anyway–they simply embraced the idea that while the Bible is true, it does not contain all truth that exists, that is, it does not contain all the information in the entire universe, nor was it ever intended to do so. It did not mention North and South America and Australia and many other places, because that was outside its focus. But that had no bearing on whether those places exist or not. The same idea can be expressed by the fact that I, along with most of the readers of the Bible throughout history, am not specifically mentioned in it by name, yet each of us are assured we exist–so the Bible not mentioning aliens in the way we understand them in modern times doesn’t necessarily mean anything.

Objection 2: The Bible says mankind is “created in the image of God.” So if we are in God’s image, anything else that does not look like us would not be in God’s image. So no other form of intelligent life can exist.

This one is contradicted by the Bible when it describes angels differently from humans, such as the seraphim of Isaiah 6…they are intelligent, but don’t look like us. Which indicates its entirely possible for God to create intelligent life in space with no resemblance to human beings. And why would aliens necessarily have to be in the image of God–could it be that God could create intelligent life that is not in his image? And can we be certain that they wouldn’t be in His image, even if they looked different from human beings? Perhaps the “image of God” is taken a bit too literally when we think of the human race. God is able to see and hear…we have eyes and ears. God is able to move and we have legs; he creates and we have hands. God is aware of himself and plans for the future and we human beings, in His image, do the same sorts of things…if that’s what’s meant by the “image of God” (I can’t say for certain this is what the “image of God” means, but I suspect it’s the case) this is a trait we human beings could well share with extraterrestrials, even if they look very different from us, if there are any.

Note that showing aliens that resemble creatures in the Bible represents opportunities for Christians who chose to write about aliens, but wish to do so in a distinctive way. A Christian writer of aliens could make them resemble one of the four faces represented in the seraphim, as I suggested in a personal blog post years ago ( The four faces around the throne of God–faces of aliens?). In fact showing any unusual beast described in the Bible, even if it’s one that has only symbolic meaning such as physical description of the “Beast” in Revelation 13:1-2, represents a potential opportunity for a Christian writer to portray aliens in a unique way. Imagine if the behemoth or leviathan of Job is met in space as an alien species, or if an alien race happens to look like the attacking monsters from the “Bottomless Pit” in Revelation 9 or were to have seven heads and ten horns like Revelation 13. This sort of thing could probably be overdone, but I think some opportunities for interesting story ideas revolve around aliens who resemble Biblical creatures.

Objection 3: The Bible teaches the Earth is the center of the universe and if there are aliens, clearly their existence would show the Earth is not be the center. So nobody who believes the Bible should believe there are aliens.

First off, this particular objection is more like a strawman argument of what Christians supposedly believe rather than what Christians really think. Not all Christians take the Bible literally at all, but among those who do (including me, except for clearly poetical or figurative parts), I don’t believe we would agree the Bible teaches the Earth is the physical center of the universe–the Bible does not actually talk about the universe in terms in which it makes sense to discuss a center. It simply says, “the heavens and the Earth”–the world we live on and the sky that surrounds us. True, Psalm 93:1 says “the Earth cannot be moved”–which doesn’t say it’s the center of anything–and it doesn’t even say that the Earth “does not move,” but rather that God has established the world as what it is and no one else can change that i.e. “move it.” There are other passages, mostly in poetic sections in the Bible, but also in famously Joshua 10 (“the day the sun stood still”), which talk about the movement of the sun across the sky. First off, these passages are quite few in number. Second, they are from the point of view of the observer on the ground–and yes, I myself see the sun move across the sky. It is true that some theologians in the past used the Bible to justify the geocentric system of the universe devised by certain Greek philosophers…and who ignored certain passages of the Bible that did not line up with that system (including the mention of innumerable stars, which the Greek philosophers did not believe in, because they counted all the ones they could see and were certain there were no more).

My first answer was a little bit unfair in a sense, because even though according to what I understand, the Bible does not actually state the Earth is the physical center of anything, it nonetheless does clearly put our world at the center of a spiritual story. And it makes sense that it would be–the Bible is the book for us after all, we human beings. But look at it another way–an implication of the Theory of Relativity is that all points of view of all observers are valid–time and space are variables affected by velocity and mass…which means there does not exist any absolute grid across the universe, nor any completely universal time clock, which means that each and every individual place is a much the center of the universe as any other. So why would Christianity be challenged to find out first-hand that aliens would see their own “center of the universe” as being every bit as important as we see our own? Our “heavens and Earth” without further specification would be just like their own view of their heavens and home world. And Christian theologians have long stated that God is Omnipresent–which means He is everywhere, in the center of every single place, throughout all space and time.

Creating aliens that see their world as the center of the universe like we humans have tended to do carries with it the hazard that it is only by conceit that either we or aliens have seen our respective worlds as important. That’s certainly the approach secular sci-fi writers have tended to take. But it’s also possible to show that both the aliens and ourselves were correct in our thinking–both places are important, not only to the beings who live there, but also to God. The implied opportunities for Christian authors here is one I’ve seen Christian writers of aliens employ before. That is, show God reaching out to alien cultures entirely independently of what He did in relation to human beings, demonstrating both that world and our world are important to God.

Objection 4: The New Testament says Jesus is the Savior of the world. That would mean that He is not the Savior of any other worlds. Why would God save only human beings and no one else–it would not make sense for God to create aliens if Jesus just died for this world–so there must not be any aliens.

The first two sentences don’t follow logically as also seen in the first answer I offered. Just because Jesus is the Savior of our world and no others are mentioned, it does not stand to reason He could not also be the savior for worlds we currently know nothing about. Besides, who says aliens need saving? Perhaps any aliens which exist are not themselves sinful. That is, they could have a sense of conscience they perfectly follow at all times. This is a possibility that C.S. Lewis offered up in his space trilogy, especially the first two books. Or perhaps aliens could be demonically evil, consistently violating their own sense of right and wrong at all times, and like demons, disinterested in repentance.

Note that portraying aliens having different attitudes in regard to sin represents opportunities for a Christian speculative writer. Aliens (or fantasy creatures) could be shown to be pure of conscience, like Adam and Eve in the garden. They could be shown to be wholly devoted to good, like angels, or to evil, like demons. Or they could be shown to respond to Christian missionaries and accept the gospel–or could be shown to have their own concept of a savior, in whom they either do or do not trust. (What if the only Son manifested himself in the form of an alien on alien worlds?)

By the way, the New Testament Greek word for “world” in John 3:16 (as in “For God so loved the world…”) is the word, “Kosmos,” which, yes, you guessed it, can mean “universe” as well as “world.” So John 3:16 could be read, “God so loved the universe, He gave His only Son…”

Objection 5. The New Testament makes much of Jesus being of the same sort of being we are–a descendant of Adam, which makes Him suitable to die in our place. Obviously he could not be the same sort of being that aliens are, so He could not be their Savior, so God must not have made any aliens (because that would be cruel).

First off, that assumes aliens would be sinners, which they may not be, as addressed in the question above. What “sinners” means is having a sense of moral conscience, being aware of violating this conscience against your own will at times–that is, a sense of sin and a need for repentance and forgiveness. If humans encounter aliens and find that they like us are “sinners,” I think it can be safely said that Christian missionaries will immediately want to preach the gospel to them. And if these aliens accept Jesus as their Savior, it would stand to reason people will say that Jesus being human was important in spiritual terms, not in the literal physical sense.

Concerning whether aliens could have their own Savior or not, which I suggested under Objection 3, Christians might offer a secondary objection, based on passages like Hebrews 10:12, which plainly state that Jesus died once for all sins for all time. So clearly He could not have died here and then later (or earlier) died on an alien world…or was that just talking about Jesus dying just once? If so, would an alien equivalent of Him count?

Also, it could be that “aliens” we meet are actually somehow descendants of Adam and Eve, transported by unknown technology of the past. I’ve seen this done before in a story that was submitted to me as a publisher which I chose not to publish because of style issues–but the idea remains a possibility in a story setting. Even if these descendants of Adam and Eve look very different from us because they’ve been genetically engineered or are cyborgs, there are story opportunities in having aliens actually be descendants of the original human couple mentioned in the Bible.

In addition, Opportunities for unique story ideas could center around the notion that the Word made flesh (as Jesus is shown to be in John 1:1-18) were in fact actually the same being for all races of beings, human and alien alike, the same spiritual reality with differing bodies–at the same exact time. What if all versions of the single Savior were at the same time and died at the same time, in effect, dying only once, even though simultaneously in many places? (after all, God can be everywhere at once, so why would not the Savior be able to die in more than one place at once? even though that is not what we would expect from what we’ve read in the Bible). Or even if the times were different on different planets, what if the times were somehow all identical from a heavenly perspective?

Opportunities also exist in showing Christian missionaries evangelizing alien species and them responding, as Lelia Rose Foreman did so interestingly in her Shatterworld Trilogy.

Objection 6: Alien encounters described by UFO believers sound much like Medieval encounters with demons. Since we know from the Bible that demons are real, that means UFOs are fake and the so-called aliens involved are fake–these are actually demonic encounters!

As I’ve said elsewhere, maybe. But even if UFO encounters were generally demonic, it would not necessarily follow that all of them are demonic, would it? And even if UFO encounters were all demonic, it wouldn’t necessarily stand to reason that there are no aliens. It would simply mean the UFOs don’t represent the real aliens that may actually exist on other worlds, beings we have yet to encounter. This opinion on UFOs actually has nothing to do with whether there are aliens or not.

By the way, I don’t know if aliens exist or not–I don’t think there is any way I can know without actually meeting one or some other form of direct evidence. It’s interesting to me though that some atheist friends of mine are utterly convinced aliens must exist…even though they state they are atheists due to a lack of evidence of the existence of God…but I digress.

Opportunities exist in playing up the contrast between encounters with real aliens versus UFO encounters. Plus, wouldn’t it be interesting if we met aliens who like us had their own legends of encounters with UFOs?

Objection 7: The New Testament has a story of the end of time (mostly in Revelation, but based on Daniel, Isaiah, Zachariah and other passages of Hebrew Scriptures) that is going to happen too quickly for there to be any time to find aliens. And no aliens are mentioned there. So there are no aliens–or we human beings will never meet them, anyway.

I believe the Scriptures deliberately put the Christian believer into a state of being that continually expects the return of Jesus at any time…and I don’t think that it’s an accident that it’s been so long. Yet, if it’s been two thousand years, why couldn’t it be twenty thousand years before the end? Granted, there are a number of things in these prophetic passages that sound very much like modern conditions to me (especially Israel literally reestablished as a nation, true since only 1948)–or sound like certain interpretations of these passages, I should say. Yet history shows that same sorts of things can happen over and over again in human events. The Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem, the Greeks under Antiochus Epiphanes destroyed it, the Romans destroyed it, and it seems the Antichrist will destroy it again. Events in history mirrored in prophecy repeat like that, like motifs in music.

It could be that human beings will spread out over time to many worlds, meet many aliens…and then undergo a long slow collapse back to just one world, our own, reproducing a number of conditions familiar to Biblical students of end times, twenty thousand years from now. And then the end could come. In short, we just don’t know how much time there is. So in terms of time, human beings living on the Planet Earth we know may well being in place long enough to meet aliens someday. Or perhaps we will only meet them in eternity, not mentioned in the Bible, but included among the things that are true which the Bible hasn’t mentioned to us in detail.

Opportunities exist in portraying future histories that appear to completely clash with Biblical end times prophecies–yet the prophecies wind up coming true in a literal, futurist sense nonetheless, via historical events unexpectedly repeating themselves, including human beings finding them limited to Planet Earth once again. Another approach would be to see aliens–or claims of aliens–in Revelation, as per my blog post Alien God of the Christian Rapture.

Objection 8: Certain Bible passages, including Acts 17:24-26, Isaiah 45:18, and Psalm 115:1, seem to rule out human beings living anywhere but on Planet Earth, which would seem to rule out us ever travelling to other worlds and meeting aliens (and also imply only the Earth can be inhabited).

The first of these passages, Acts 17:24-26, simply states that God has put human beings on the Earth and set where they will live there. That doesn’t say all human beings live on Earth or that humans must eternally live on Earth–note human beings have already dwelt in space, in orbit, on a more or less permanent basis.

Isaiah 45:18 simply states the Earth was made to be inhabited–which doesn’t mean it is the only place made to be inhabited.

Only Psalm 115:16 of these three passages represents any problem at all, because it says the heavens are the Lord’s but the Earth he has given to mankind. That certainly seems to imply God’s intent was for human beings to remain on Planet Earth and stay out of the “heavens.” But you could say this isn’t talking about the physical heavens, but rather heaven in a spiritual sense, which human beings don’t have any right to enter on our own terms. Certainly it is true that God is also to be found on Earth, even though God is “in the heavens.” Likewise we know humans will eventually be in heaven, as in the place of God’s presence, if believers no longer alive on Earth aren’t in fact there already. So us being intended for one place doesn’t seem to exclude us being in another places as well.

Opportunities exist in stories that show the difference between the heavens as in outer space and heaven(s) in a spiritual sense. A story could also show a series of human outposts in space being wiped out for mysterious reasons and then someone quoting one or more of these verses. Even if the problems with the colonies is not in fact linked to any form of divine judgment, having characters wonder if it was linked could be an interesting story development.

Conclusion: Aliens, which have become a common piece of modern American popular culture as much as zombies or vampires or superheroes, but which are thought to really exist by some very serious and intelligent people, should pose no insurmountable challenge for the Christian writer who wants to represent a worldview consistent with Christian doctrine, yet one that nonetheless includes extraterrestrials. And numerous opportunities exist for Christian writers to overcome the objections listed above, while simultaneously portraying aliens (or fantasy creatures) in a different light than what “secular” writers of science fiction do.

This latter was a remarkably large and beautiful animal, entirely black, and sagacious to an astonishing degree. In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise. Not that she was ever serious upon this point—and I mention the matter at all for no better reason than that it happens, just now, to be remembered.

This latter was a remarkably large and beautiful animal, entirely black, and sagacious to an astonishing degree. In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise. Not that she was ever serious upon this point—and I mention the matter at all for no better reason than that it happens, just now, to be remembered. On the night of the day on which this most cruel deed was done, I was aroused from sleep by the cry of fire. The curtains of my bed were in flames. The whole house was blazing. It was with great difficulty that my wife, a servant, and myself, made our escape from the conflagration. The destruction was complete. My entire worldly wealth was swallowed up, and I resigned myself thenceforward to despair.

On the night of the day on which this most cruel deed was done, I was aroused from sleep by the cry of fire. The curtains of my bed were in flames. The whole house was blazing. It was with great difficulty that my wife, a servant, and myself, made our escape from the conflagration. The destruction was complete. My entire worldly wealth was swallowed up, and I resigned myself thenceforward to despair.

Paul Regnier is a speculative fiction author perpetually lost in daydreams of spaceships, magic, and the supernatural. He is the writer of Paranormia, an urban fantasy/supernatural comedy (read an excerpt

Paul Regnier is a speculative fiction author perpetually lost in daydreams of spaceships, magic, and the supernatural. He is the writer of Paranormia, an urban fantasy/supernatural comedy (read an excerpt

Even when one’s preferred Halloween vibe is low-level creepy rather than outright scary, the “creepiness” is rooted in fear. Inflatable spiders and cartoony skulls and adorable zombies are still tethered to our innate fears of death and creepy-crawly things, even if we don’t actually feel fear when beholding these images. Likewise, when we see a latex-molded slaughter scene in someone’s front yard, we might feel a tingle in our spine but this is because these innocuous plastic props hearken to the real thing, even though we have likely never actually seen “the real thing.”

Even when one’s preferred Halloween vibe is low-level creepy rather than outright scary, the “creepiness” is rooted in fear. Inflatable spiders and cartoony skulls and adorable zombies are still tethered to our innate fears of death and creepy-crawly things, even if we don’t actually feel fear when beholding these images. Likewise, when we see a latex-molded slaughter scene in someone’s front yard, we might feel a tingle in our spine but this is because these innocuous plastic props hearken to the real thing, even though we have likely never actually seen “the real thing.”

It was a transcendent experience of the beauty of Godâs creation and made me understand the literal truth of something being âbreathtaking.â

It was a transcendent experience of the beauty of Godâs creation and made me understand the literal truth of something being âbreathtaking.â

of pure logic, ghost stories imply an immortality of the soul, even if a kind of immortality that no one wants. But immortality is for the living, and ghosts are nothing but dead. Ghost stories offer no glimpse of the other side. It is, after all, the special tragedy of ghosts that they donât make it to the other side but linger, without point or place, on this one.

of pure logic, ghost stories imply an immortality of the soul, even if a kind of immortality that no one wants. But immortality is for the living, and ghosts are nothing but dead. Ghost stories offer no glimpse of the other side. It is, after all, the special tragedy of ghosts that they donât make it to the other side but linger, without point or place, on this one.