Most days, I write about something awesome at the corner of biblical faith and fantastical stories. But it is not this day, in which I speak again as a DC film fan and supporter of the #ReleaseTheSnyderCut fan movement for the movie Justice League.

Over the weekend, that hashtag trended on Twitterâa few weeks before Justice League theatrical version’s two-year anniversary.

That recently swelled fan response was spurred by cast and crew of the movie Justice League. They had released some behind-the-scenes bits that got fans all excited.

I don’t join a lot of fan movements. I’ll sleep tonight even though Firefly will never get a second season. I felt vexed at the notion of yanking Spider-Man back out of the Marvel-verse, but not enough to sign petitions about it. And, apart from supporting Young Justice season 3, I haven’t thought about even slacktivism to insist that my favorite cancelled show get another chance.

But the night after I saw Justice League‘s theatrical cut in theaters (in November 2017), I headed straight for the internet to find a petition to release the real movie. Two years later, the movement has only grown. They’ve posted banners near cons, started a website, and everything.

Stephen M. Colbert (DC fan, not TV comedian) summarizes the #ReleaseTheSnyderCut battle cry:

Justice League was well on its way to becoming aesthetically and tonally similar to Batman v Superman (although a lighter, more hopeful movie had been promised since before Batman v Superman even released) and Warner Bros. and DC Entertainment execs were tired of getting the same criticisms every time, so Snyder was finally pushed out of the project after completing 100% of principal photography and some post-production, and Joss Whedon reshot a large portion of it to change the story, brightening the lighting and colors, and adding more jokes. Fans were told [original director Zack] Snyder left due to a family tragedy (he did suffer the loss of his daughter during production) and Whedon would simply finish his existing vision, but it was very clear upon release that finishing Snyder’s vision hadn’t been the intent, and fans started campaigning for the movie Warner Bros. had promised them.

Those are the basic facts. But here’s why I support the hashtag and suggest that even Snyder critics should at least not get all grumpy about it.

1. No one is a raving fan of Justice League‘s theatrical version.

1. No one is a raving fan of Justice League‘s theatrical version.

Some folks didn’t hate the theatrical (per)version of Justice League. But it has no raving fans.

Which makes little sense, if it were true that people really only wanted “fun” and “light” DC heroes without challenging themes and ideas.

Here on SpecFaith, for the series Justice League v the Legion of Doom, Kerry Nietz, Austin Gunderson, and I didn’t hate the film. We enjoyed quite a few parts of it. But we still lamented wasted opportunities:

Stephen: The characters are great. I love each and every one of them. But this rushed story and world around them felt shallow and empty. Sometimes literally. ⊠Cities around them had no life. It needed another full hour. It needed Snyderâs deft hand in the editing and post-production.

Austin Gunderson: Steppenwolf was no match for Superman. Thatâs been the key strength of the previous films to me: that Superman wasnât boring. I thought this movie managed to Make Superman Boring Again. Not because he was unlikable, but because he won so much I got tired of winning.

Kerry Nietz: If I had to name a fault, it would be in the stakes. They needed to create more of a sense of global peril. That could have been easily done with more small scenes in different locations. Possibly those are the types of things that were left on the cutting room floor.

By contrast, all (leaked) images and plot details from the originally planned film promise a far more epic and complex storyline.

2. Imagine if this same thing happened with Avengers: Endgame.

Imagine thisâonly just two hours long, with no seriousness and a dull soundtrack.

Let’s say that Avengers: Infinity War (2018) had been met with some controversy as well as enthusiastic fan-praise.

Or, even if not, suppose that Avengers directors Anthony and Joe Russo had already shot their three-hour epic hero-fest Avengers: Endgame. They’d begun early marketing and showed some amazing stuff in the trailers. The film’s score would be similar to previous films (from composer Alan Silvestri). And fans already knew to expect this three-hour epic that would celebrate united heroes and finally resolve the previous film’s cliffhanger.

But then suppose the Marvel producers had balked at the idea of releasing the movie like this.

Suppose they really, really didn’t want to spend the first 30â45 minutes of the movie showing how hopeless everything was.

And suppose that instead they cut down Tony Stark’s story, refused to let any hero die, and bluffed past consequences of the Decimation. Oh, and fired Silvestri and replaced him with John Debney (last seen doing his best with Iron Man 2).

Result: a shallow, two-hour version of Avengers: Endgame designed to avoid risks, please “masses,” and get shown more often in theaters.

You and I would have done our best to like it. But then we would have headed to the internet to join the movement #ReleasetheRussoCut.

3. Even if you disagree with #ReleaseTheSnyderCut, why deny fans the chance?

Let’s say you’re one of those chaps (including some of my friends) who despised Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Like many fans (and critics), you associate the film with “grimdark” nastiness, or all the Wrong Ways people try to hijack superheroes.

Fair enough.

Either way, the DC films moved in the direction you said you wanted: with “fun” Aquaman (2018) and “fun” Shazam (2019). (I loved both.)

And the dream of an epic theatrical Justice League team-up filmâmuch less a story split into two or even three partsâis now dead.

So it’s not like, if the Snyder Cut were actually released, that’s going to take away from those more crowd-pleasing DC hero films.

Aren’t you even the least bit curious if those “grimdark”-supporting fans were right, and the original, non-tampered Justice League would have been more to your liking? Especially when that risk comes with equal odds that #ReleasetheSnyderCut fans won’t really like what they see after they get it, anyway?

4. Anyhow, folks wrongly accused earlier DC Universe films of being ‘grimdark.’

Just another “grimdark” moment of killer awesomeness.

I’ve been around this debate a few times, partly as a DC fan, and partly because I’m also a fan of respecting story creator’s stated intentions.

In this case, when a creator says, “I made the story to do X,” then it’s unfair at best, and slanderous at worst, to act like they’re lying.

Back after Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice released, we shared this argument versus the “grimdark” accusation:

Austin: I think anyone who calls this movie âgrimdarkâ probably doesnât know what the word means. Wikipedia defines it as describing a âtone, style, or settingâ that is âmarkedly dystopian or amoral, or particularly violent or realistic.â . . .

Batman v Superman dares to go where few superhero films have ever gone before: into a moral universe so similar to our own that even the good guys sometimes get it wrong. And only when the right choice isnât blindingly obvious can a film such as this provide a meaningful commentary on the world.

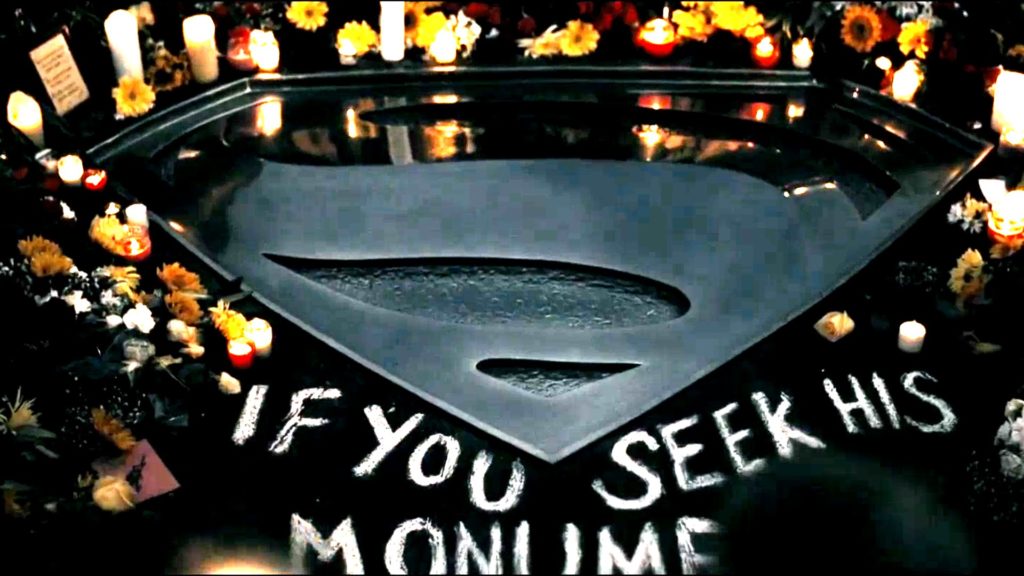

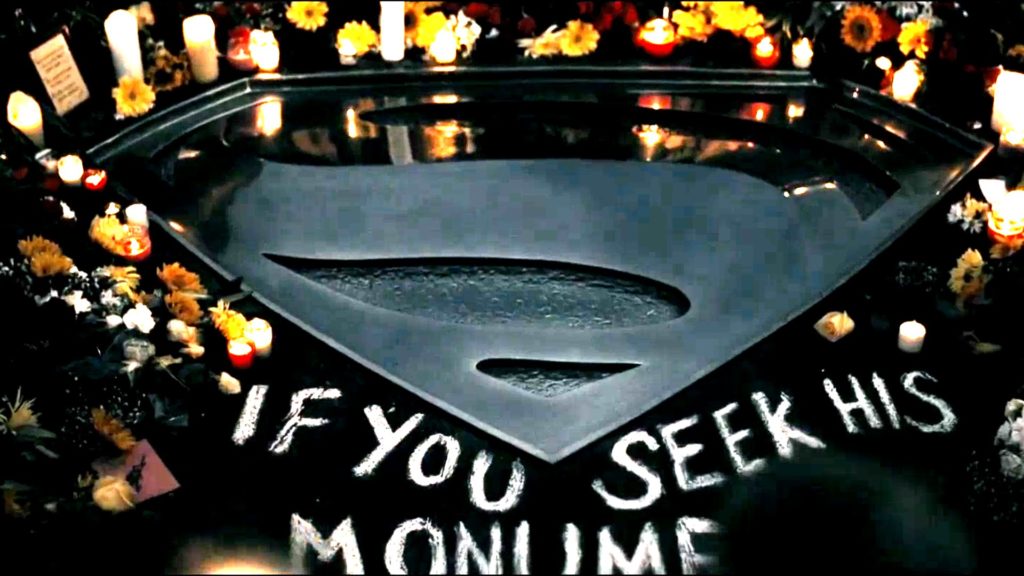

Just another “grimdark” moment in which a sincere hero makes the ultimate sacrifice, and the story pauses for blatant celebration.

For a while I’ve claimed Man of Steel, Batman v Superman, and Justice League were/should have been perceived as nobledark:

A kind of epic fantasy meets grimdark in that the world is dangerous and horrific and scary, is stuck technologically because larger than life monsters tend to destroy everything every once in a while or the world is dying out for some reason, but there are noble warriors that rise up to protect people from the horrors and / or save the world.

Nobledark â grimdark. Know the difference.

5. Either way, original Justice League would have been (or will be) amazing.

Folks who’ve tracked the #ReleasetheSnyderCut campaign have followed the behind-the-scenes “leaks” about what awesome twists, complexities, and heroic moments Zack Snyder’s originally planned Justice League would have offered fans.

And that’s after pushback that saw the film reduced from part-1-of-2, and made even “brighter” and into a more easily accessible standalone.

It’s just those “leaks” that have changed the minds of my friends and I.

We went from saying, “Well, Justice League as-is wasn’t that bad,” to lamenting “Yeah, we was robbed.”

Of course, I say that tongue-in-cheek. But recently, Kerry, Austin, and I talked again about our support of the #ReleasetheSnyderCut push:

Austin Gunderson: It’s really something to see. Time was when a Joss Whedon script physicking was a seal of quality. Now people are kickstarting grassroots campaigns to get his contributions expunged.

Kerry Nietz: It is a matter of tone and intent. What we got clearly wasn’t what was originally intended. So if you’re a fan of the other two movies, yeah, you’re going to wonder. And part of me suspects that Whedon was lackluster in being brought in the way he was. I imagine some Warner exec bringing him in and saying “Just make it like Avengers! We want Avengers!”

Stephen: Which, I’m sure, can’t have been impressive or respectful of him. Whedon can do “nobledark” when he jolly well wants to.

Austin: I dunno. I actually think Whedonâs pretty one-note. Which, granted, is a note that everybody typically loves, but I havenât seen or heard of much from him that doesnât fall into the crew-of-charming-rogues-crack-wise-and-chew-scenery-whilst-in-dire-peril category.

Kerry:

Austin: He was perfect for âThe Avengers,â because it was a movie about a crew of charming rogues cracking wise and chewing scenery whilst in dire peril … and nothing more than that.

But Justice League was in another league entirely. As the third in a series of dark, somber, mythopoetic examinations of superhero sociology, it needed to maintain a continuity of tone while upping the stakes. Whedon wouldnât have been capable of doing that even if WB had prohibited him from straying from Snyderâs vision.

The strength of Man of Steel and Batman v Superman comes from their sincerity: Snyder really felt that he was making something epic and important, and he had sufficient skill to convey that sense instead of coming across as pretentious. But no oneâno matter how skilledâcan pull that off unless he himself has the degree of sincerity (innocence? faith?) heâs seeking to elicit in his audience.

People say that comedy is the hardest kind of writing because laughter is an objective metric. But I actually think that mythopoeia is dang hard, too, because of the degree of sincerity involved. Even the tiniest bit of cynicismâWhedonâs calling cardâwill kill it dead.

Stephen:But this also explains why the two films thus far met with such hostile reception.

Apart from any particular quibbles (e.g. Jonathan Kent would Never Say That, and Batman Would Never Ever Kill), the fan and critical response was influenced by particular expectations about how superhero movies should behave. And at least at the time, the zeitgeist declared that Marvel movies (or their perception of Marvel movies) were the in color, and anything else was last year’s fashion.

Of course, to the extent that these criticisms were based on vapid trend-following and âforecasting, they were not sustainable. The genre still had to grow up, and Batman v Superman and original Justice League were simply a few years ahead of trend.

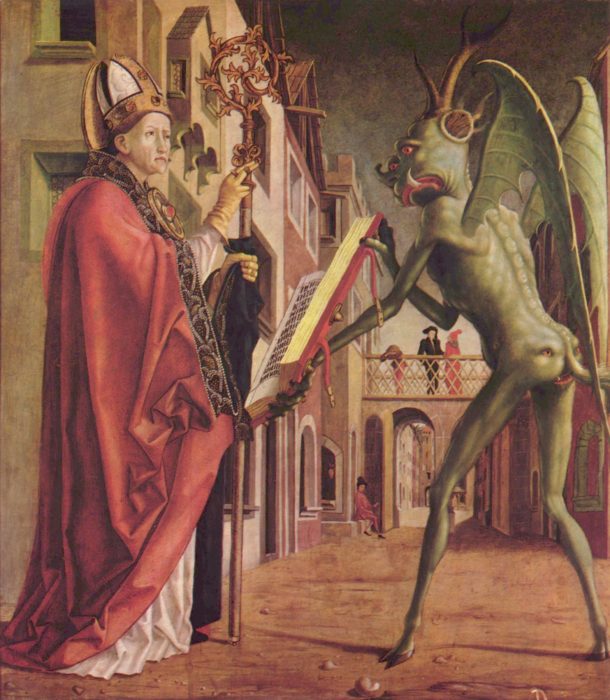

*Artist’s representation.

Now, however, “serious” superhero films are becoming cool again. Studio meddling with “Justice League” showed people just exactly what they claimed to wantââlighter” DC moviesâand it failed so hard. Then Marvel tried to “go dark” and epic in its own wayâbut only after winning fans’ trust on other terms. (Anyway, it’s doubtful we’ll get more Marvel films anytime soon with the scale and thematic sweep of Infinity War/Endgame.)

Meanwhile, Logan and now Joker have proven that you can try a more-serious (even R-rated) story inspired by superhero universes, and I think critics begrudgingly admitted the results worked. And DC hit its stride with Wonder Woman, Aquaman, and Shazam. None of these has a bit of cynicism, and two of the directors even explicitly said so! Yet these films worked better as crowd-pleasers. They bridged the expectations gap. Now, people feel comfortable enough to be curious about the Justice League Snyder Cut.

I’m going to say it: I think it will happen, if not now, then sometime in a year or two.

#ReleaseTheSnyderCut. #UniteTheSeven. #MakeMyChristmas.

Saintsâ Day, with its brighter spirituality and emphasis on life after death, never gained a place. There is a great deal of opportunity for social commentary in that fact. Probably too much, actually. The celebration of Halloween, and the neglect of All Saintsâ Day, have a tangle of causes. Prominent among them is the human need for the concrete. The most spiritual celebrations require material rites, or they will never be popular. We all know what you might do to celebrate Halloween. No one can think of what you might do to celebrate All Saintsâ Day except go to church, if you can find a church thatâs open.

Saintsâ Day, with its brighter spirituality and emphasis on life after death, never gained a place. There is a great deal of opportunity for social commentary in that fact. Probably too much, actually. The celebration of Halloween, and the neglect of All Saintsâ Day, have a tangle of causes. Prominent among them is the human need for the concrete. The most spiritual celebrations require material rites, or they will never be popular. We all know what you might do to celebrate Halloween. No one can think of what you might do to celebrate All Saintsâ Day except go to church, if you can find a church thatâs open.

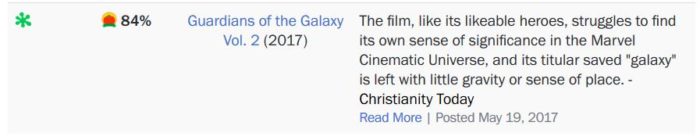

Still, I must be fair. If at that moment in May 2017, if you demanded that I call my Vol. 2 review “fresh” or “rotten,” I would have had to say “rotten.” Only under duress. Most of my review did focus on ways I felt the movie failed to meet its own goals, or contradicted its own themes. But Rotten Tomatoes didn’t ask me this question. Instead, someone else chose a quote from it. And they stuck a little “splat” icon beside the review, interpreting my creative workâitself an interpretation of James Gunn’s space-comedy filmâas saying, “That movie is rotten.”

Still, I must be fair. If at that moment in May 2017, if you demanded that I call my Vol. 2 review “fresh” or “rotten,” I would have had to say “rotten.” Only under duress. Most of my review did focus on ways I felt the movie failed to meet its own goals, or contradicted its own themes. But Rotten Tomatoes didn’t ask me this question. Instead, someone else chose a quote from it. And they stuck a little “splat” icon beside the review, interpreting my creative workâitself an interpretation of James Gunn’s space-comedy filmâas saying, “That movie is rotten.”

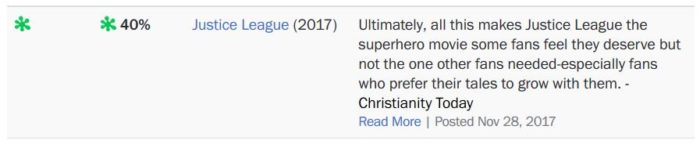

In either case, this movie, Justice League, would only be “good” or “bad” depending entirely on what you expected about it.

In either case, this movie, Justice League, would only be “good” or “bad” depending entirely on what you expected about it.

For this next I must again rely on a chap called Stephen M. Colbert (fandom writer, not TV host). While exploring the responses to DC’s new superhero universe-inspired movie Joker,

For this next I must again rely on a chap called Stephen M. Colbert (fandom writer, not TV host). While exploring the responses to DC’s new superhero universe-inspired movie Joker,

Following his vision of the coming Messiah, the prophet Daniel creates a select group of men who will count down the calendar to the arrival of Israel’s promised king. Centuries later, as the day nears, Myrad, a young magi acolyte, flees for his life when his adoptive father and others are put to death by a ruthless Parthian queen.

Following his vision of the coming Messiah, the prophet Daniel creates a select group of men who will count down the calendar to the arrival of Israel’s promised king. Centuries later, as the day nears, Myrad, a young magi acolyte, flees for his life when his adoptive father and others are put to death by a ruthless Parthian queen.

Every day at Saint Bernard is filled with readings from the Scriptures, both at the Divine Office and in personal reflective reading of the Bible, or lectio divina. Lectio is one of my favorite parts of my day as a monk. Biblical heroes came off the page and my love for fantasy adventure, which never went away in my life, was combined with my love for the Bible.

Every day at Saint Bernard is filled with readings from the Scriptures, both at the Divine Office and in personal reflective reading of the Bible, or lectio divina. Lectio is one of my favorite parts of my day as a monk. Biblical heroes came off the page and my love for fantasy adventure, which never went away in my life, was combined with my love for the Bible.

This also got me thinking: when does the future arrive? Media, entertainment, and scientists have been painting a picture of the future that almost never lines up with reality when it arrives. Have you ever seen 2001: A Space Odyssey? It wasn’t meant to be a blueprint for life at the turn of the century, but I’m sure moviegoers in 1968 thought that at least some of the fantastic scenarios in that movie would come to pass when the new millennium arrived. Of course, now we know better, but we’re still captivated by visions of life in the mid- or late-21st century. The far future is fun to imagine as well but I think most people are interested in a future that will conceivably come about in their lifetimes.

This also got me thinking: when does the future arrive? Media, entertainment, and scientists have been painting a picture of the future that almost never lines up with reality when it arrives. Have you ever seen 2001: A Space Odyssey? It wasn’t meant to be a blueprint for life at the turn of the century, but I’m sure moviegoers in 1968 thought that at least some of the fantastic scenarios in that movie would come to pass when the new millennium arrived. Of course, now we know better, but we’re still captivated by visions of life in the mid- or late-21st century. The far future is fun to imagine as well but I think most people are interested in a future that will conceivably come about in their lifetimes.

1. No one is a raving fan of Justice League‘s theatrical version.

1. No one is a raving fan of Justice League‘s theatrical version.

That our service personnel are willing to put their lives on the line, to step up and do the work to defend what we all enjoy, means more than I can ever express. We are blessed to have brave Marines and infantry, seamen and airmen, the Coast Guard and all those special ops individuals. It really is amazing to think that so many people are willing to set aside a desire for fame or wealth or comfort or ease to step up and stand in the gap for the rest of us.

That our service personnel are willing to put their lives on the line, to step up and do the work to defend what we all enjoy, means more than I can ever express. We are blessed to have brave Marines and infantry, seamen and airmen, the Coast Guard and all those special ops individuals. It really is amazing to think that so many people are willing to set aside a desire for fame or wealth or comfort or ease to step up and stand in the gap for the rest of us.

Let me share a personal story from my own life. Years ago I read a book by Francine Rivers called Redeeming Love. Although my favorite genres are science-fiction and fantasy, I decided to try a romance novel because I had heard so many great things about this particular one.

Let me share a personal story from my own life. Years ago I read a book by Francine Rivers called Redeeming Love. Although my favorite genres are science-fiction and fantasy, I decided to try a romance novel because I had heard so many great things about this particular one.