Imagination: For Godâs Glory and Othersâ Good, Part 5

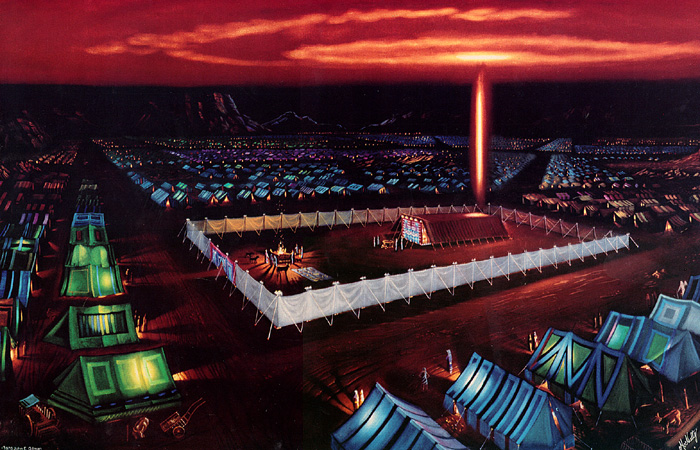

The Tabernacle: only the first clear example of God desiring glory through His people's imaginations.

Some Christians (actual or otherwise) abuse their own imaginations, and no oneâs insistence that imagination, like sex, is a good thing will by itself solve their heart corruption.

Others may use their imaginations, yet suspect it would be more âspiritualâ to focus only on nonfiction and avoid supposed corruption by imagination. And to resolve that, it takes a Biblically based Theology of Things to show why sanctified imagination can glorify God.

So many examples of Godâs people glorifying Him through creativity are found in Scripture, matching perfectly the Bibleâs more-direct encouragements to honor Him in all that we do; I suspect a whole book could be written drawing these out.

In this series Iâve explored only a few people, Bezalel (and Oholiab), who used their gifts to honor God with His people; and Daniel, whom God gifted to stay holy and yet also be a light for Him in an abjectly pagan society, even as Daniel studied actual pagan-religion materials. All of these honored God in creativity and vocation, in both âchurchâ and âworldlyâ settings.

Now we come to the final and best example of imagination for Godâs glory. This is so clear a proof that Iâm almost sure if we went too far with it, weâd reverse churchesâ usual practice and claim that storytelling, more than singing, honors God better.

After all, we could say, Jesus is mentioning singing a hymn once (Matt. 26:30, Mark 14:26), but never is He said to have written a song â and yet He told dozens of stories!

After all, we could say, Jesus is mentioning singing a hymn once (Matt. 26:30, Mark 14:26), but never is He said to have written a song â and yet He told dozens of stories!

I wonât go that far. But it would be an interesting argument-by-logical-conclusion to suggest this to someone who does not see the point in Christian storytelling (or worse, suspects it as equivalent to lying)! Bezalel, Daniel and many other Biblical figures help support the truth that Godâs people can honor Him and share His truths in new ways with their God-given imaginations. Yet we only need Christ Himself to prove this!

What can our Saviorâs stories show us about storytelling, for Godâs glory and othersâ good?

Iâll try to address a few points here, but really, this does deserve a book-length treatment âŚ

Were Christâs parables truly fiction?

The first time I clearly heard "Jesus' parables could not be fiction" was in this book. Of course, its author opposed that notion.

Thereâs a notion about Jesusâ stories, which I first read about in TED DEKKERâs nonfiction book The Slumber of Christianity. It claims this: Jesus could not tell lies, so one way or the other, His parables must have actually been descriptions of things that really happened.

Were Christâs parables historical and not fiction? Perhaps they were; surely at least some of them were close enough to His hearersâ realities that they could think, say, about the story of a woman who lost her coin, I know someone like that. Other general comparisons, such as a shepherd going after a lost sheep, or men harvesting grain, surely had real-life parallels.

But elements from several parables seem to show they had to be stories:

- First, the very fact that weâre confused about the parablesâ historicity gives credence to the idea that they were fiction. To prevent confusion, why would Jesus have not said (a la sports-movie trailers): Based On a True Story?

- Only in one parable did Christ name one of the chief players, Lazarus, and includes the real-life figure Abraham. And that was in one of the wildest of His parables, with communication between compartments of Sheol and everything (Luke 16: 19-31).

- Shepherds, sowers, or an unjust judge may have been common in Jesusâ day. What about the kings in several of the parables, who are never named? In one such story, Jesus says âthe kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who âŚâ (Matt. 18:23 and onward, emphasis added), but never names the king or states he was real.

- Several of the figures Jesus mentioned have some very strange fantastical powers, if indeed they were historical! In two parables, found in Matthew 22 and 25, one king, and a man returned from a long journey, both punish people in a way impossible in the real world: they have the villains cast âinto the outer darkness.â Whoa. How would a real-life king get access to âthe outer darknessâ? These are perhaps the clearest examples of Jesus drawing upon âfantasyâ to illustrate reality.

Were Christâs parables only to teach Values?

Iâve been trying to find written support for the idea that parables must be real, but it seems sparse. One online site I did find was this one, in which the writer doesnât so much condemn stories as express his own nervousness about them. (When he says that reading Jurassic Park made him wonder if it was real, I suggest he might need to avoid fiction, but others need not do this.) Yet when he mentions a purpose of fiction, I have a more-vital question âŚ

We tell fiction to entertain, and sometimes (more often in the past) to carry a moral, to train people in virtuous character. Morality is good, but does the end justify the means?

Goofiness like turning Gideon into a high-school band player is okay, only if it's also "A Lesson in Trusting God."

This perception is frequent: fiction is only either entertaining or meant to show a Moral Point. Of course, many Christian stories try to do both. VeggieTales DVDS, for example, have on their covers bright colors and fun characters, but also assurances for Parents and Legal Guardians that this story gives âA Lesson in [Moral Behavior].â In effect this is an attempt to âmake upâ for being fun and entertaining by also teaching a Value â a kind of penance.

But where did the entertainment-or-Value clash come from in the first place?

Was that Jesusâ purpose in telling parables â only to give entertainment or to Moralize?

Either excess breaks down when one considers Christâs true purpose: not merely to repeat the Law and Prophets, but to fulfill them (Matt. 5: 17-20) and proclaim âThe time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospelâ (Mark 1:15). Moreover, earlier in Luke 16, before His fantastic story set in the afterlife, Christ tells about a dishonest manager. His account is meant to restate His point that even His disciples can learn from the businessmanâs foresight and preparation for the future, though without using his methods.

Not all actions described in Christâs parables are moral. He didnât mean them to be. Rather, He used any story elements from allegory, reality, or even fantasy, to support His mission: to fulfill the Law and the Prophets, and to call others to ârepent and believe in the Gospel.â

Jesus: the ultimate storyteller, beyond only allegories

Hereâs another belief I used to hold about parables: they are all allegories. Maybe this belief gives rise to the notion, often well-meaningly applied to praise C.S. Lewisâs fiction or to oppose other non-allegorical stories, that if we do tell stories, they must be Allegorical.

But is it true that every one of Christâs parable is a direct Allegory, which includes specific parallels between figures and objects in the story to spiritual meanings in real life?

I'm indebted to "How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth," which I recommend even if only for the chapter on reading the parables and the "allegory-only" belief.

Many Christians might bring up Mark 4: 1-20. Here, Jesus does tell a direct-allegory story â the parable of the sower â then seems to say all parables will be like this, then draws out the meanings only for His disciples. So all His stories must have secret meanings, they say.

Others, though, portray Christâs parables as only intended as a sort of populist presentation, a way to reach the people in their language and make His truth memorable.

I see no reason why His purpose canât be both. In fact, Scripture supports both. Christ told at least two kinds of parables: either closed-captioned for His disciples only (as in Mark 4: 10-12) or to make a point for a broader audience (as in Matthew 21: 33-46). This may also have applications for Christian storytellers today: we can tell stories for both âsets.â

But if Christâs parables were only allegorical, what do we make of His story about a dishonest and shrewd manager (Luke 16), or His very short story about man who sells all he has to buy a field with treasure (Matt. 13:44)? If we tried to force them to be pure allegories, we might conclude that Godâs Kingdom could conceivably be built with shrewd and dishonest business practices, or even that we earn salvation. But thatâs not the genre or intent of those parables.

When Jesus explained to His disciples the sower parableâs meaning, He never claimed all parables would be direct allegory. Instead we find that He constantly varied His style:

- Sometimes He explained allegory parablesâ meanings. Other times we donât see this.

- Stories that begin with âthe kingdom of heaven is like âŚâ do not mean you need to listen to the story and find which Thing represents the Kingdom. Rather, His term âlike âŚâ applies to the thrust of the entire story. This can be seen in Matthew 13 alone, in which He tells about a man seeking treasure, in which the treasure could seem to represent the Kingdom, but then says âthe kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearlsâ (verse 45). Here, the Kingdom is not the merchant. Instead the Kingdom is shown in the whole story: the worth of the things sought.

- Some of His parables contained meanings that were closed-captioned for His disciples. Others were targeted to nonbelievers, as in Matt. 21: 45: âWhen the chief priests and the Pharisees heard his parables, they perceived that he was speaking about them.â Often He would vary his approach based on His audience at the time.

- Sometimes Christ would ask openly âWhat do you think?â Then, oddly enough, He would go on to say exactly what His point was (as seen in Matt. 18:12 and onward).

- Christ told similar stories with different points, such as two version of the lost sheep (such as Matt. 18: 10-14, about straying believers, and Luke 15: 1-7, about a shepherd pursuing a stray nonbeliever). Again, He varied the story, based on His audience.

- Jesus used fantastical elements in at least two stories, mentioned before, in Matt. 22 and Matt. 25, about leaders who punished the wicked with âouter darkness.â

That last leads to one finding that seems startling on the surface: In many of Christâs parablesâ âstory-worlds,â God Himself is never mentioned as existing! In fact, many of Jesusâ stories presume Godâs âabsence,â yet in service to the real world in which God, His truths and Kingdom and Gospel, are unavoidable.

What applications, I ask, might that have for Christian storytellers today?

Might this also gives us Scriptural support to write parables or stories in which God is not shown as a key player, but which illustrate truth about Him and His Kingdom anyway?

What else might you have found in Christâs parables, which has helped you as a reader or even writer of visionary fiction, or even other genres? Something I missed here, perhaps? Another element that needs to be clarified, so that Iâm not making my own stories about His stories, and so that I can add to that Jesusâ-parables-and-fiction book Iâve already started?

God can be glorified in imagination. Jesus Himself did this, and blessed others by helping them grasp His Kingdom truths. His people, for His Kingdom, can do the same with all his good gifts â echoing His old truths in new ways, in many genres, even the fantastic ones!