But the LORD is the true God;

He is the living God and the everlasting King.

At His wrath the earth will tremble,

And the nations will not be able to endure His indignation.

Thus you shall say to them: âThe gods that have not made the heavens

and the earth shall perish from the earth and from under these heavens.â

He has made the earth by His power,

He has established the world by His wisdom,

And has stretched out the heavens at His discretion.

~Jeremiah 10.10-12

God and Humanity

Once upon a time, the earth was void and formless, and the Spirit of God hovered over the deep. He spoke, and the universe appeared, a perfect, magnificent place with worlds, stars, meteors, moons, and suns. A place with countless galaxies–all of which he named to the last speck of dust and declared good. He barred off the ocean and scooped up the mountains. He grew animals from the bottom of the ocean, the clay of the earth, and the clouds in the sky. He planted a garden never duplicated and made a clay figurine, then breathed into its nostrils and gave it breath. He took a rib from his clay man and made a woman out of bone, and she too breathed.

Once upon a time God, angel, man, and beast walked together, fearless and full of joy and vitality.

Once upon a time, the Great Cosmic Tragedy came, and the entire Universe screamed as the throes of Death began. Thus began the Great Rift, thus began the day first blood ever spilled. Something else happened, though, the day the worlds writhed in pain. The first hand of mercy reached down, picked up the creature that hated it, and covered its shame in robes. Thus began the middling part, where Man and God and Beast made war, all the Cosmos in a fright because their kings brought sin and death, shuddering and weeping, appalled and gasping.

But be not dismayed, desperate universe: His servants enough he’s sent; now your king sends another, the great prince who above all rules. The final act’s begun. Life fought with Death; and Death delivered his most wicked stroke. For a moment’s breadth the Cosmos thought that all was now a loss.

But then came a new song.

“Where, O Death, is your victory?

Where, O Sin, is your sting?

The Firstborn has come from among the dead;

He’s dragging you in chains;

Adam’s curse fell to the Holy One;

The Great King has a victory won;

Where, O Death, is your victory?

Where, O Sin, is your sting?

Hear the song of those back from your maw, O Death;

Know that he has crushed your head;

Abram’s sons sing the song;

Sarah’s daughters, sing along;

Where, O Death, is your victory?

Where, O Sin, is your sting?”

The song grew in height, width, and breadth, and Death’s blows only strengthened the sound. Louder and louder, sweet victory went out; and all Creation learned the sound. The Dread Champion has gone to war against the Dark. He’s confident of the final piece, enough to display his battle plans and offer a peak at the epilogue; he’s written a glorious ending, and he has but one thing left to say–

“Come.”

” Remember the former things of old,

For I am God, and there is no other;

I am God, and there is none like Me,

Declaring the end from the beginning,

And from ancient times things that are not yet done,

Saying, âMy counsel shall stand,

And I will do all My pleasure,â

Calling a bird of prey from the east,

The man who executes My counsel, from a far country.

Indeed I have spoken it;

I will also bring it to pass.

I have purposed it;

I will also do it. “

~Isaiah 46.9-11

Time Lord

Once upon a time there was a man from another world.  The Earth was one small, helpless planet, a childlike bright spot in the midst of a dark, dangerous universe. They called the man many things: godlike, an angel–for better or worse–the cosmic ‘fix-it’ man and janitor. He never turned down a cry for help, and he preferred to preserve life rather than destroy it.

He’s a terrible god: all-powerful, overly-intelligent, vain, and selfish as often as he is selfless. He’s beaten and broken, betrayed and abandoned by his own people, in desperate need of redemption…and offered only endless rebirths. He’d love to save everyone, this intelligent, powerful king of time and space. But as he looks down at the worlds, he knows he can’t save everyone, can’t undo fixed points or rearrange the flux of time. The cosmos keeps creaking, cracking, breaking, leaking, and warping, and sometimes all he can do is look on in horror.

Sometimes, he tries to fight against Time itself, a pointless effort, tries to go against the natural course of things and can’t. He has his dark moments and sometimes becomes childishly angry. He’s flawed and often contradicts his own principles, usually when he’s blinded to a more palatable option. His way might not be the only way, but he thinks it the best.

âHeâs like fire and ice and rage.

Heâs like the night and the storm in the heart of the sun.

Heâs ancient and forever.

He burns at the center of time and can see the turn of the universe.

And â and heâs wonderful.â

~ A Boy, Family of Blood

The Doctor may well be king of the universe, but he’s certainly not its Emperor, Creator, and Sustainer. He is himself servant to Time, stolen away and kept a willing captive by the vortex of time that serves as the heart of the TARDIS, a creature who doesn’t always take him where he wants to go, but always where he needs to be.

How oddly…human.

“Very old…and very kind.”

~Amy Pond, “The Beast Below”

“That’s just what they’re called. It doesn’t mean he knows what he’s doing.”

~ Amy Pond, “The Doctor’s Wife”

Blessed are the…

For whatever reason, I get the impression the Doctor both sees humans as better than Time Lords and as something he’d like to be. It’s never outright said, but it pretty well culminated for me in the Human Nature/Family of Blood episodes. In his mind, humans are a bizarre combination of emotion and intelligence, beauty and ugliness, good and evil. Perhaps in a weird way he sees humans as the next Time Lords: similar to them, but without the things that caused their downfall.

TARDISÂ Code:

- Strive for peace – You don’t kill unless there’s not an alternative. (I’m doing a separate piece on violence, pacifism, and non-violence next time.) Don’t go looking for a fight.

- Trust each other.

- Strive for hope. Life is hope.

- Don’t be foolish. Be calm, be brave, and be fast on your feet.

- Don’t subject yourselves to tyranny.

- Oppose oppression, violence, and disregard for life are evil.

- Mourn the loss of life.

- Prefer mercy.

For him, moral discrepancies are oppression, exploitation, foolishness, and violence are immoral; whereas just about everything else seems to be acceptable. Because he lies, he needs his friends’ trust. Because he’s lonely and/or can “go dark,” he needs friends. So they can’t always trust him, often have to deal with the emotional and/or physical trauma he creates, and occasionally have to remind him he’s not a Dalek.

Who humans are to the Time Lord

- They’re his responsibility. He protects them, not the other way around.

- He’s in charge. Always. Unless the companions mutiny…which tends to happen, because he doesn’t ever pick submissive types for friends.

- Humanity’s overall principles should be embraced. (It makes you wonder: If the Time Lords “went bad,” then what was their crime? Oppression? Tyranny? Failure to protect life?)

- One episode (the one with the Dream Lord, who I still think might come back) suggests he knows he’s a conniving, manipulative old man who runs around time and space with very young friends, and in a weird way he worries he simply uses and disposes of them for his own selfish game…like stray pets to keep the loneliness at bay. Oddly, Donna embraced the idea and Martha rejected it. Amy told him to shut up; but that’s Amy for you.

- To put it in the Doctor’s words, “You can spend the rest of your life with me; but I can’t spend mine with you.”

- To him, humans (or rather, anyone not a Time Lord) are small, finite creatures in constant need of help whether we like it or not, but he seems hopeful of the day when humans don’t need saving anymore.

The best humans have to offer**

Now, he tells Rory and Amy in season five that he chooses his friends well, “only the best,” so to speak. He sees himself as old and full of darkness, but his “children” as young and full of light. But if that’s the case, let’s do a quick, Spark Notes version of the Doctor’s “children”:

- Rose–One thing I really miss is how everything in her seasons was an adventure, a game, down to wearing costumes for each episode. I never thought of the Doctor and Rose as a couple, so in that I evidently differ from most fans. Just never bought it. She liked him, and she’s openly affectionate like her mother, but to me Rose, Mickey, and Jackie were family. She was sweet, she was fun, but in the end I just saw her as a friend, and I felt like she saw him the same way. Someone pointed out she’s the strong one between the two of them, and they’re probably right in some respects. She’s an odd mix of tough and gentleness, and that itself is appealing. In her words: “If I leave him, well, then, he’ll be alone.”

- Martha– I liked Martha, but, again, wasn’t buying what felt like a forced “love interest” yet again. Martha just never stood a chance, really. It wasn’t her fault (save her initial infatuation, maybe). Just the timing. He was never going to let anyone back in that soon. Probably what defines Martha is her resilience: She forces him to open up to her in Gridlock; she won’t take his nonsense; she’ll stick with him to the bitter end…and it’s a very bitter end. Even her refusal to stay with him says more about her unwillingness to enter a codependent relationship than anything else. She can’t save him. He doesn’t want her to, because he’s too busy pushing everyone away. In her words: “I can’t stay with you. But you better answer your phone when I call.”

- Donna–I didn’t like Donna in Runaway Bride (nor did I ever fully comprehend her freak-out over killing the Racnoss), but she redeemed herself in season four immediately. Thankfully, there was no forced love interest with Donna. She’s also a little older than the other two, and I think that helps. She’s brassy and impulsive, almost a composite of the previous two. In her words:  “I’m going to stay with you forever.”

- Wilfred – Donna’s grandfather, who provides a ‘fatherly’ figure for the Doctor, especially at the end. He’s not officially a companion, but he’s there when the Doctor is in some severe need of a friend, so I’m adding him. He’s a sweet old man…and someone the Doctor respected and admired. He doesn’t realize until the end how much older than him the Doctor is, which is likely why he jumped so easily into that role. He doesn’t say much, but I think in the end he’s the only thing that prevents the Doctor from refusing to regenerate.

Edit: Galadriel gave me some great Wilfred quotes. She says:

A good pair of quotes for Wilf comes from End of Time

The Master: (to the Doctor) Oh, your dadâs still kicking up a fuss.

Wilfred: Yeah, well, Iâd be proud if I was

and later, on the spaceship,

The Doctor: Iâd be proud.

Wilfred: Of what?

The Doctor: If you were my dad

Now thatâs a huge compliment for the Doctor to make of anybody.

- River–River comes first because, technically, we meet her first. I just like her, probably because she is such a foil for him. She’s got the whole ‘female Indiana Jones’ thing going on, and breaks just about every one of the Doctor’s principles. She makes Daleks beg for mercy and gives the Doctor the jitters. (And half the time she’s doing what I *wish* the Doctor would do and just shoots the bad guy already.) Her words are, of course:

Doctor: “You graffitied the oldest cliff-face in the universe!

River: “You wouldn’t answer your phone!”

- Amy–Amy’s a character I like without actually being able to say why. She’s tough and sassy like Donna, but not as overbearing. She’s childlike and too experienced all at the same time. And she usually sees straight through the Doctor’s mask and reduces a complex person down to something simple. My only real wish is that she’d stop treating Rory so horribly. I’m not sure if Amy’s should be “He’s very old and very kind” or “You’re late for my wedding!”

There’s also:

River: The Doctor’s a complicated man. You really think it could be something that simple?

Amy: Yes.

River: Oh, you’re good.

Actually, I think my current favorite is:

Amy: Cool aliens?

Doctor: What do you call me?

Amy: An alien.

Maybe we can take votes on Amy’s line. 0=)

- Rory–Rory is the ‘anti-Doctor,’ which is probably why I like him so much.  While the Doctor is tall and loud and all over the place, Rory’s smallish, quiet, and still. It isn’t weakness. It isn’t fear. And with all the Type A insanity going on in the TARDIS, he serves as a much-needed anchor forcing everyone back into reality. He’s another tricky one to come up with a one-liner for. I think maybe this one works, as it very much tells you that, despite their differences, Rory respects him:

Rory: He wants revenge?

River: Not his style.

Amy:Â To save him?

Rory: Also not his style.

And really, it’s mutual, I think, as Rory’s the one the Doctor leaves at the helm in The Hungry Earth. (If that episode did nothing else, it created a situation for the Doctor to give Rory that.)

So there they are, in all their flawed glory. A heavy mix of strength and weakness, flawed heroes to the last: all following the king of the flawed heroes.

“The human race: such an intelligent lot you are, and also so sensible; *

give anyone a chance to take control and you submit.

Sometimes I think you like it. Easy life.”

~ The Doctor, Rise of the Cybermen

Human Nature

Covenant Code:

- be poor in spirit

- be meek

- mourn

- be hungry and thirsty for righteousness

- be merciful

- be pure in heart

- be peacemakers

- those persecuted for righteousness’ sake

- love mercy

- do justly

- walk humbly with their God

- fear the Lord

- love the Lord with everything they’ve got

- love their neighbors

Who we are to the Lord of Time and Space

- created in his image, perfect and beautiful, with his emotions and creative spirit (marred though they be now)

- fallen and broken, in need of redemption

- finite and small

- made “a little lower than the angels”

- proud and in rebellion

- kings and queens of the earth, even if we’ve lost our own dominion

- made to fill the earth, subdue it, and rule over it

- his creatures, whom he loves

- prodigals

- fall into either the category of wicked or righteous

- fail to acknowledge God as God and give him thanks

- tend to serve the creature rather than the created

- wicked in the heart (“You, being evil, know how to give your children good gifts”)

Of whom the world is not worthy

The God of the universe says the best we have to offer amounts to nothing. Human glory is but the moon reflecting the sun: the greater light is the glory of God himself. Human goodness is laughable in the face of the Most Holy. He made our brains, but he certainly doesn’t expect our wisdom to even compare with his. Human intelligence is impressive only to other humans–largely because there is so much we can’t see or fathom. Human beauty is dross before his magnificence; human strength is nothing before his might. We cannot grasp the total Otherness of the God of the Universe.

Scripture has its own ‘short list’ of God’s companions. It’s not an exhaustive list, but it finishes up by calling the saints of God “men of whom the world was not worthy.” In fact, it’s everyone who fits under this label that Hebrews calls “so great a cloud of witnesses.” I don’t know that God would call them “the best” because he doesn’t think about us that way. He calls us salt and light, he calls us thick, strong oak trees planted by an everlasting stream, always producing fruit, always a place of rest for anyone coming by. He calls us saints, co-heirs with Christ, Christ’s brothers, friends, servants, slaves of righteousness, a holy nation, chosen generation, royal priesthood, called out, set apart ambassadors, his children. He knows who we were; he knows what we are.

And really, he only has one thing left to say about it: “You are mine.”

*I tried three or four times to get this phrase right. I’m mostly sure that he said “and also so sensible,” but if someone knows otherwise I’ll correct this. For the life of me, I couldn’t understand that part.

**I omitted Jackie, Mickey, and Jack, and anyone else because they aren’t companions. Wilfred got included because he did actually serve a companion’s role, sort of in the same way Samwise was also a Ring-bearer.

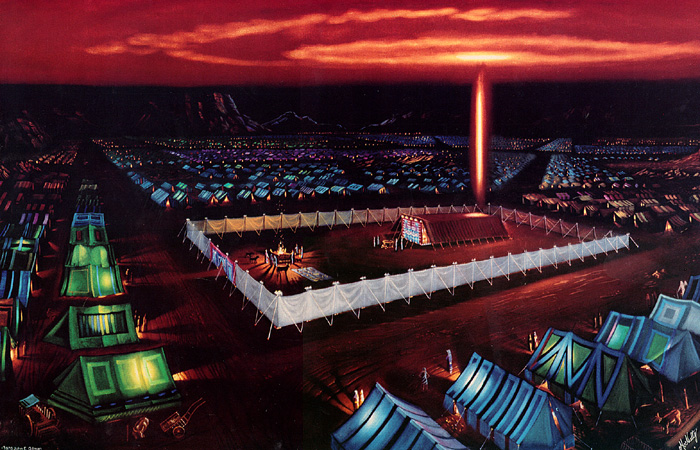

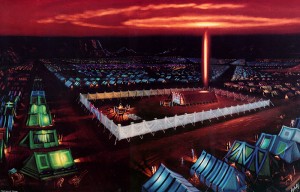

For more, I highly recommend Phillip Graham Rykenâs short but readable book overviewing how art is supported in Scripture: Art for Godâs Sake. He covers these chapters in Exodus about the Tabernacleâs artistry very well, and for those who see the connections between the Covenant then and how it carries over to now (which Iâm still working to understand), itâs so encouraging to God-glorifying imaginers today that they, too, can find Biblical heroes.

For more, I highly recommend Phillip Graham Rykenâs short but readable book overviewing how art is supported in Scripture: Art for Godâs Sake. He covers these chapters in Exodus about the Tabernacleâs artistry very well, and for those who see the connections between the Covenant then and how it carries over to now (which Iâm still working to understand), itâs so encouraging to God-glorifying imaginers today that they, too, can find Biblical heroes.