Human Nature 1: On The Enemies List

Bad guys. Villains. Antagonists. Weâve been talking about love on this site, courtesy of Fred Warrenâs series. Now, concurrently, Iâd love to start a new series about those we love to hate.

Bad guys. Villains. Antagonists. Weâve been talking about love on this site, courtesy of Fred Warrenâs series. Now, concurrently, Iâd love to start a new series about those we love to hate.

Or, as we may find, one enemy we should love to hate â but too often instead love to love.

Of all conflicts, I believe that battle proves the most intense of all.

But who among us entirely despises conflict itself? In some ways, we like conflict, and thatâs okay. Without it weâd have no story. In fact, Godâs own true-life story, the Epic Story, alone proves this. Though sovereign and infinite in His holiness, knowledge, and love, He thought it best to permit evil in the world, from several sources, to bring the most glory to Himself.

Part 2 will explore those sources. Scripture mentions three of them. Yet first, it seems beneficial to explore something Iâve noticed in most stories â including speculative novels and films, but going beyond them: a recurring cast of enemy characters.

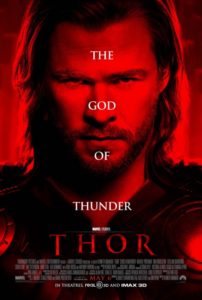

Example: superheroes dominated last summerâs hot films, followed by alien-invasion flicks. Yet even apart from recent filmsâ antagonists, the types of bad guys always seem the same.

Bottom-ten hits

People will sometimes talk about the Thirteen (or Sixteen, or Twenty, or whatever) Basic Plots of Stories, which I have often thought is silly because all good stories, anyway, will always follow the Single Basic Plot based on the true Epic Story: good guys, bad guys, conflict, resolution. Less often do people make lists of the (Number) Basic Villains of Stories.

Here Iâve come up with ten, and tried to sort them, in order of least-evil to most-evil.

- Scientists, mad and otherwise.

- Political liberals or government.

- Atheists and/or Communists.

- âFundamentalistâ âChristians.â

- Evil Big Business.

- Political conservatives, government, or military.

- Satan and/or demons.

- Space aliens or other magical/supernatural creatures.

- Organized crime and/or supervillains.

- Hitler/Nazis.

Unusual: In “Captain America: The First Avenger” (2011), The Red Skull is even badder than bad-guy standbys Hitler and the Nazis.

What would this order say about how we think? Of course, you may suggest a revision. In what order would you place those enemies? What enemy categories would you add?

Surprise enemies?

Furthermore, what kinds of stories intentionally flaunt these conventions? We do see more of that going on, as screenwriters and novelists are doing their best to come up with more-creative approaches to story conflicts than the usual tropes. Christian movie reviewer Paul Asay of PluggedIn.com wondered why, in his April 2010 article âThe Vanishing Villainâ:

Truth is, itâs hard to find a bonafied [sic] villain anywhere in entertainment now. Oh, there are plenty of characters who are âquirkyâ or âmisunderstoodâ or perhaps even âunpleasant to be around due to unresolved issues.â But most seem more in need of a good shrink or hug than a judgment-laden slapdown.

Which begs the question: Are there still villains out there that canât be helped with a hug? Are there dragons too dangerous to tame?

Iâm not sure Iâd agree with his assertion that itâs harder to spot villains in entertainment. Rather, real villains seem here to stay. Even Asay recognizes this. After citing animated films like How to Train Your Dragon and Meet the Robinsons, both of which have plot twists showing who the ârealâ villain is, Asay mentions The Dark Knight and its infamous villain The Joker. Heâs one enemy who is completely evil. He cannot be saved. Only stopped.

Iâm not sure Iâd agree with his assertion that itâs harder to spot villains in entertainment. Rather, real villains seem here to stay. Even Asay recognizes this. After citing animated films like How to Train Your Dragon and Meet the Robinsons, both of which have plot twists showing who the ârealâ villain is, Asay mentions The Dark Knight and its infamous villain The Joker. Heâs one enemy who is completely evil. He cannot be saved. Only stopped.

But even the films Asay thinks have âvanishing villainsâ still have villains, just Not the Ones You Were Expecting. The enemies who seemed obvious simply werenât the real bad guys.

For example, to slightly spoil How to Train Your Dragon, wild dragon Toothless and others may not be the villains, but the concept of Villainy certainly didnât vanish. At the climax of the story the Viking heroes find the real foe, and conduct an epic battle to destroy him.

Sometimes such twists prove anti-clever. The âsurpriseâ gray-area revelation about the Real Villain is easy to see coming. And once the âtwistâ is done, we can revert to good-versus-evil.

Other times, the heroâs response to the villains is flat-out confusing. Assuming here a mostly upright, straightforward protagonist, such a hero can easily figure who are the real villains who will not change, and who are the disadvantaged types who are simply oppressed or taking orders from the real bad guy. Meanwhile audience members are either left to wonder how the hero can tell the difference, or else think theyâre certain they can know a difference simply because theyâre told there is difference. In Dragon, for example (which I love), the Vikings had misunderstood the dragons and simply needed to coexist with them. Yet why not apply this same principle to the kingpin dragon at the end? How did they know that creature wasnât also oppressed and needed to be given a chance?

Bad guys make for tricky discernment. Most people know, and Christians know Scripture teaches (Matthew 7:11), that even evil people can do good things and there are âgray areas.â

Yet everyone yearns for just-plain-bad-guys somewhere. Outside ourselves. Easy to see.

And that leads to my own attempt at giving a âclever twistâ about the Real Villain. This enemy rarely gets on the list. But itâs worse than all of them. It lurks behind them all. Even the Nazis. And come to think of it, itâs âsurprisinglyâ shown right there in this seriesâ title.

Next week: The battle lies within.