Today I feel like a good old-fashioned, and I hope Christ-exalting, rant. This one focuses on popular reasons to love The Chronicles of Narnia and similar stories. Such reasons miss the beauty of a literary forest, in favor of esoteric, specific Bible-quoting spiritual symbols and Allegories that are supposedly carved into the trees â if you look very closely. (Or rather, you teach children to look, because you assume Narnia is only for childrenâs Moral Benefit.)

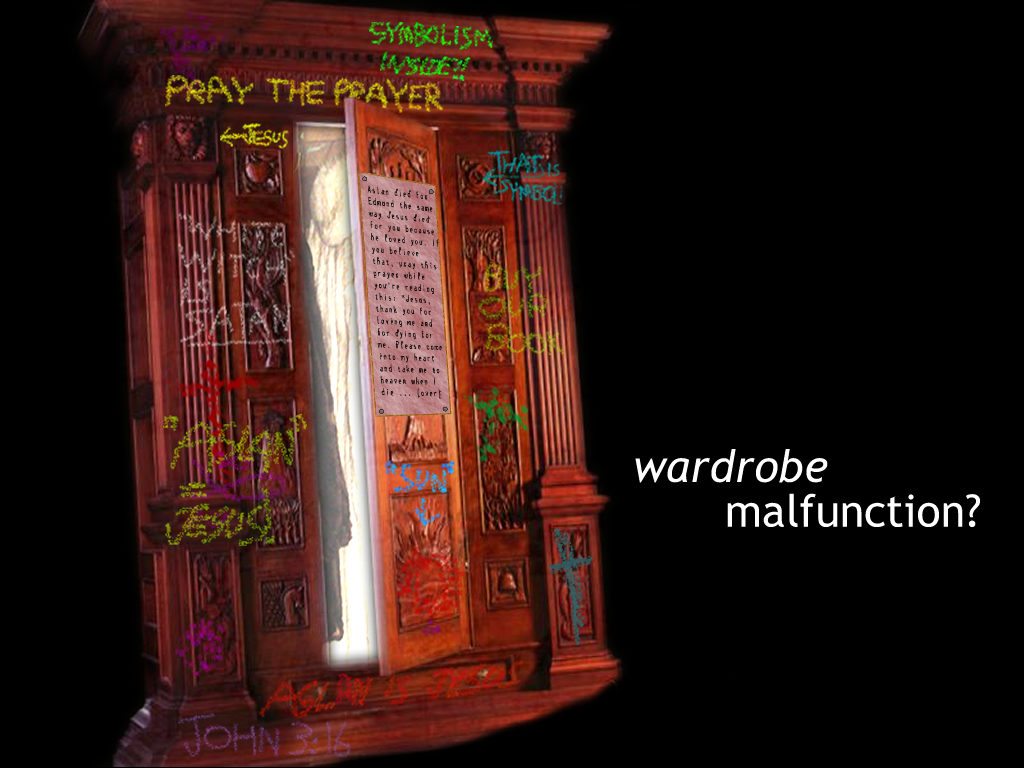

Donât put silly spray paint all over the Wardrobe. Its magic world within, and (in the film) the symbols carven without, should first share their own story.

Here, and in part 2, Iâll base my critique on this article. Its author is Peter Hammond. I only recognize the name and Iâm sure he means well. He gets plenty right, such as that Narnia is a âsupposal.â But then he sadly goes off violating fantasy-story âhermeneuticsâ in a way that no evangelical Christian would do â or should do â with a certain other Book we enjoy.

Do I pick on this because these flawed Narnia justifications are irksome, and because I just finished a local-church reading group for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe? Absolutely.

Yet my main reason is because this is a question of worship.

I mean this: that if you view a story like LWW in this way, you will worship God less.

A sermon parallel

Does Aslanâs death signify Christâs? Yes. Does the story contain symbols and allegories? Yes. Do Christians overreact to silly or liberal âmetaphoricalâ approaches to Scripture and thus claim the âliteral meaningâ precludes any symbols, callbacks, or parallels in the Story? Yes.

But let us take a famous Bible verse, such as John 3:16. I read this verse, in context, aloud in front of a group of people. I have no idea if these are âprofessionalâ Christians, new Christians, or Biblically ignorant or Biblically fluent non-Christians. So I read aloud: âFor God so loved the world âŠâ and so on. Let us say I fix on the meaning of the word world. I do a study on the differences between the Greek aion (age, I believe) and kosmos (physical creation). I discuss other uses, symbols, parallels, and more. Then I end with, âLet us pray.â

Is this bad? No; we need such deep-delving. Is this untruthful? Again, no. So whatâs wrong?

This: I should have first proclaimed the textâs central, beautiful truth. âListen! God loves His creation. According to His love, He gave His only Son so that all those who believe in Him will not be condemned but live forever. What an amazing Story about an amazing God! Has He saved you? If so, you will want to respond to Him. Exult in Him. Delight in His beauties.â

Now watch what occurs when someone approaches a story such as LWW, surely with good intentions, but with primarily a fill-out-symbolic-checklists-on-behalf-of-others emphasis.

First, what does that approach miss?

- In place of a spirit of worshipful delight and wonder is an air of stiff approval.

- In place of having the heart of a child is having the heart of a childâs Instructor.

- In place of an eye for beauties in the subcreatorâs writing, and the Beauty of the Creator Himself, is a wandering glance that seeks Obviously Practical Truths.

- In place of humility âunderâ the story is a salvage effort to seek parts for Good Use.

Narnia vs. certain other fantasy stories

Unfortunately, because of the success of the âHarry Potterâ series, many have assumed that the âThe Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobeâ is something similar. However, while Lewisâs âChronicles of Narniaâ have a Christian worldview, the âHarry Potterâ books and films are occultic.

One should not gloss over such LWW criticsâ alarms over âocculticâ elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sinâs real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of âtaking captiveâ âpaganâ myths, any âbut itâs allegoryâ-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

One should not gloss over such LWW criticsâ alarms over âocculticâ elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sinâs real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of âtaking captiveâ âpaganâ myths, any âbut itâs allegoryâ-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

As for Harry Potter [HP], in the writerâs defense, he seems to have written this in 2005, two years before the HP series ended with a brilliant echo of Christâs sacrifice and defeat of evil. Yet in the authorâs offense, he repeats myths about the HP series even by that time.

C.S. Lewis made clear in his writings that it is wrong to use magic.

The writer gives no source for this claim. I donât recall Lewis speaking on the topic of real-world âmagicâ (or defining what âusingâ it would look like in reality). Discerning readers must tangle with Lewisâs love of âoccultâ myths and fairy-stories, to understand his views.

Magic is forbidden in the Bible (Deuteronomy 18:8-13; Leviticus 19:31; Revelation 21:8).

It would help to define briefly why God forbids this âmagic.â It is not imaginary magic that only exists in folklore, but willful attempts to reject Godâs power and means of revelation in favor of our own attempts to predict the future or control our lives. By this higher standard, using devices such as Ouija boards would be wicked, but so would be âChristianâ methods of divination that fear Things, or try to seek Godâs secret will in âsignsâ to know our futures.

This writer does rightly understand Narniaâs use of âmagicâ to mean Godâs laws or miracles.

The worlds that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien described in their novels were real worlds with real consequences and real hope. Actions have consequences. When Edmund succumbs to the temptations of the White Witch, he has to pay the consequences, or someone has to pay in his stead. In contrast, the âHarry Potterâ books are thoroughly occultic.

This is incorrect. Why do Christians repeat such myths? Actions also have consequences in the Harry Potter world, and the series roundly condemns relativistic views of good and evil.

In their ontology, the world can be manipulated through magic. Things change shape. Nothing is really real. There is no need for a Saviour.

Again we see why simplistic defenses of Narnia are undiscerning. In Narnia, the world can also be âmanipulated by magic,â and âthings change shape.â As for ânothing is really real,â this repeats a postmodern, my-interpretation-over-the-authorâs-intent mode of reading HP.

One merely has to have the right incantations and formulas to manipulate reality for oneâs own selfish ends.

In Narnia, as in Harry Potter, these sinful behaviors are shown. And by the end of the Harry Potter series, they are also condemned. In either series, characters sin, learn, and change.

Violating Narnian âhermeneuticsâ

C.S. Lewis explained that: âThe whole Narnia story is about Christ.â âThe Magicianâs Nephewâ is about the Creation and how evil entered Narnia. âThe Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobeâ is about the Crucifixion and Resurrection. âPrince Caspianâ is about the restoration of true religion after corruption. [âŠ]

Yes and no. Behold the religious tendency to crave stamping Moral X or Moral Y or Moral Z atop a story or product. For instance, that is only one theme of The Magicianâs Nephew; the story also explores human suffering, fertility and motherhood (author Michael Ward argues the story is themed after motifs based on the medieval mythology of Venus), temptation, âsupposalsâ of other worlds, and other themes. To say âthe story is about this onlyâ neglects these other meanings. It is a flawed, fill-out-the-blank approach that also lessens worship.

This articleâs writer does, however, get it right that Narnia is a âsupposal.â Here he quotes Lewis accurately and favorably. Unfortunately he then ignores Lewisâs âhermeneuticalâ hint in favor of a âFind Deeper âSpiritualâ Meanings First for Our Practical Useâ hermeneutic.

When the Witch confronts Aslan, she reminds him of the âdeep magicâ the Law that âevery traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have the right to kill.â The Witch declares that by law, his blood belongs to her. All of this echoes Romans 6:23 âThe wages of sin is death.â And Hebrews 9:22 âWithout the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins.â

As noted here, the Deep Magic is similar to Godâs Law, but not exact. One does not need to parse the Witchâs words or delve into symbols to discern this; one only needs to know that it is God, not Satan â or Death itself, as the Witch better reflects â who punishes sin. Any Christian defense of LWW should recognize the allegoryâs limitations. Otherwise we may violate the storyâs intent and read âback intoâ Scripture a foreign belief. (This is especially possible when people misinterpret the meaning of the character Emethâs near-salvation in The Last Battle to believe Lewis fully endorsed a kind of âanonymous Christianâ notion.)

Next week: approaches like this ignore the central intent of a story and the primary need to be first lost in its beauties and wonders, in favor of un-humble attempts to âspiritualize.â

One of the greatest pleasures I have as a reader of the speculative genre is discovering wonderful books I didn’t even know about until somebody waved it under my nose and told me, âHere. Read. Love.â This feature is my brief effort to pass that joy along.

One of the greatest pleasures I have as a reader of the speculative genre is discovering wonderful books I didn’t even know about until somebody waved it under my nose and told me, âHere. Read. Love.â This feature is my brief effort to pass that joy along.

Thanks to Lewis, this name is better known now than it was even 30 years ago, but many people have still heard the name without ever picking up one of his books. This is a tragedy, because MacDonaldâs works are some of the best mind-bending and world-stretching stories of the Christian fantasists.Â

Thanks to Lewis, this name is better known now than it was even 30 years ago, but many people have still heard the name without ever picking up one of his books. This is a tragedy, because MacDonaldâs works are some of the best mind-bending and world-stretching stories of the Christian fantasists.

Powers is an Eastern Orthodox believer (I believe), but certainly a Christian. His best-known novel at this point isÂ

Powers is an Eastern Orthodox believer (I believe), but certainly a Christian. His best-known novel at this point is

One should not gloss over such LWW criticsâ alarms over âocculticâ elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sinâs real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of âtaking captiveâ âpaganâ myths, any âbut itâs allegoryâ-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

One should not gloss over such LWW criticsâ alarms over âocculticâ elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sinâs real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of âtaking captiveâ âpaganâ myths, any âbut itâs allegoryâ-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

In this I seem to be in the minority.

In this I seem to be in the minority. I have no problem with Frank Perettiâs angels-versus-demons novels This Present Darkness and Piercing the Darkness, though I â

I have no problem with Frank Perettiâs angels-versus-demons novels This Present Darkness and Piercing the Darkness, though I â  For me, that may also contribute to

For me, that may also contribute to