Sorry, folks, no video this time around. The writing life has hit me a little hard and the time I needed to put a video together just wasn’t available this time around. That doesn’t mean I won’t ever put a video together again. It just means that I have to do it the “old fashioned” way this time around.

A few years ago, I was learning how to teach a Bible study curriculum called Crossways (which is awesome, BTW). Dr. Harry Wendt, the study’s author, brought out a souvenir he had purchased in Jerusalem a number of years ago. It was a picture of the Jerusalem skyline with a small alteration. Someone had photoshopped out the Dome of the Rock and replaced with a new Temple. It was one of the scariest things I had ever seen (but more on that in two weeks. Who says cliffhangers always have to come at the end of something?).

While it may have frightened me, it’s also the hope of many Jews and also many Christians, especially if they’re dispensational premillennialists. For those who hold to that particular eschatological tilt, it’s something they expect to see happen at some point. A Third Temple will be built on the site of the previous two.

But is that really what needs to happen? Do we need a Third Temple? Or has God fulfilled the concept of the Temple with something far greater? Now obviously, I’m speaking from an amillennialist viewpoint, but I would say that the answer to those three questions are, “No, no, and yes.” Let me explain.

Let’s start by talking about butterflies. For the past several years, I’ve been toying around with something I like to call “Butterfly Theology.” I’ve noticed that several concepts in the Bible go through a transformation of sorts, and they all follow the pattern of a butterfly’s life cycle (which, for those of you who have forgotten their life sciences, is egg, caterpillar, cocoon/chrysalis, butterfly). One such instance occurs with the concept of Temple:

Let’s start by talking about butterflies. For the past several years, I’ve been toying around with something I like to call “Butterfly Theology.” I’ve noticed that several concepts in the Bible go through a transformation of sorts, and they all follow the pattern of a butterfly’s life cycle (which, for those of you who have forgotten their life sciences, is egg, caterpillar, cocoon/chrysalis, butterfly). One such instance occurs with the concept of Temple:

THE EGG: This concept starts out as the Tabernacle that God commands Moses to make after the Exodus. It was a tent that will house God’s Presence, one set up in the middle of Israel (Exodus 25-31, 35-40). When Israel camped somewhere, the Tabernacle was at the heart of the camp, reminding God’s people that God dwelt in their midst.

THE CATERPILLAR: Eventually, King Solomon built a Temple in Jerusalem. When the Temple was dedicated, God’s Presence filled it with His glory (2 Chronicles 7:1-3). But because of Israel’s sin, the glory was eventually driven out (Ezekiel 10:4-5, 18-22) and the Temple itself was destroyed and God’s people were taken into exile (2 Kings 25:1-21). When they returned from exile, they rebuilt the Temple (Ezra 3). Interestingly, when they finished, the glory didn’t show up again (Ezra 6:16-18). The same thing is true when King Herod the Great renovates the exile’s Temple and makes it much larger and grander (that’s based on the writings of Flavius Josephus, who notes a number of apparent supernatural happenings before Herod’s Temple is destroyed but makes no mention of anything happening when it’s dedicated).

So it’s time for the cocoon, the time when the caterpillar is transformed in a radical way and is still the same organism somehow. When it comes to butterfly theology, the cocoon is always the same thing: Christ.

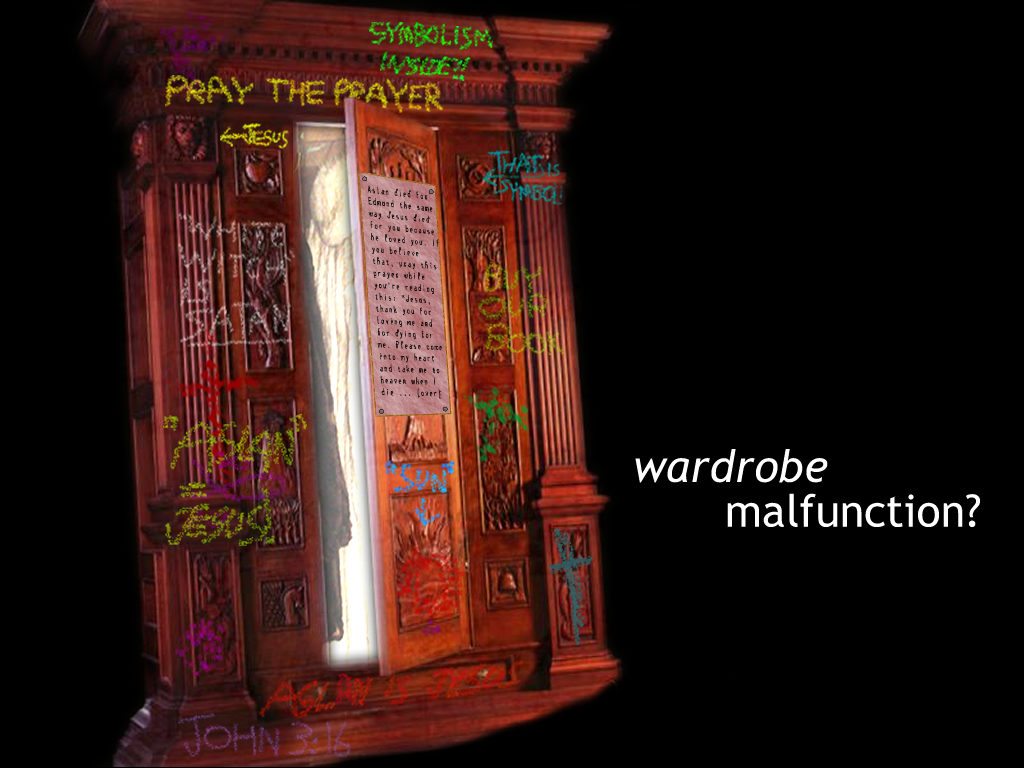

THE COCOON: In many ways, Jesus fulfills, transcends, and transforms the concept of the Temple. Think John 1:14, which uses Temple terminology to talk about how Christ dwelt in our midst (the same way the Tabernacle did). Think John 1:51, where He implies that He has replaced the Foundation Stone with Himself. Think John 2:13-22, where He refers to Himself as the Temple (a charge that would later be repeated at His trial before the Sanhedrin). In Jesus, the Glory of God (the same glory that never returned to the Jerusalem Temple) dwelt among us. He became a new and better Temple.

THE BUTTERFLY: And stemming out from Jesus, a new Temple has been built upon the foundation of the prophets and apostles, one built out of living stones with Christ as the cornerstone. The Church is the new Temple. That’s usually what St. Paul is talking about when he uses the term. That’s how St. Peter uses the term when he talks about Christians being built together as living stones. In its present form, the Temple is so much greater than a stone building in one city. It’s a way for God’s presence to be among His people all over the world, hearkening to what Jesus told the Samaritan woman in John 4:21-24.

The question I have is this: why rip the wings off a butterfly to make it a caterpillar again?

That seems to be a question that the author of Hebrews asks as well. The entire book of Hebrews, apparently written to Jewish Christians thinking of dropping the latter part. The author points out that the New Covenant supersedes the Old in every way. He makes the argument that the trappings of the Old Covenant were mere shadows of a greater reality to come. The question he asks is why would we want to go back to the shadows when we’ve seen the greater reality?

That seems to be a question that the author of Hebrews asks as well. The entire book of Hebrews, apparently written to Jewish Christians thinking of dropping the latter part. The author points out that the New Covenant supersedes the Old in every way. He makes the argument that the trappings of the Old Covenant were mere shadows of a greater reality to come. The question he asks is why would we want to go back to the shadows when we’ve seen the greater reality?

It’s a valid question, and one we have to ask about building a Third Temple. Do we really need one? The Temple was the place where sacrifices were made so sins could be forgiven. If Christ’s death is all sufficient, why do we need a place for more sacrifices? The Temple was the place where God dwelt among His people. He does that now through the Church. Why go backwards?

“But John,” some of you may be saying, “what about Ezekiel’s vision of a new temple in Ezekiel 40-43? The exile’s Temple and Herod’s Temple don’t match the dimensions Ezekiel describes. Doesn’t that mean there’s a Third Temple that needs to be built?”

It’s true, Ezekiel does seem to see a vision of a future Temple. But there’s something that’s always struck me as odd about that vision is this: where are the height measurements? While Ezekiel records the length and width of the rooms in this supposed Third Temple, he doesn’t give us many measurements of how tall the rooms are supposed to be. There are a few, but not nearly enough. If this Temple were really going to be built, wouldn’t we need full measurements in every direction to make it happen?

So what is this Temple vision? I believe it’s God’s way of trying to communicate a concept to Ezekiel in terms he can understand.

The best example I can think of is this: suppose I were to go back in time to . . . say, Martin Luther’s time. Naturally, I’d be cautious about revealing too much information about the future. But then, let’s say that something happens to my time machine and I wind up stranded in 16th century Germany. Marty takes me out drinking and I wind up spilling my guts. Er . . . bad choice of metaphor. I wind up telling him that I’m from the future. So Marty asks what the future is like, and I respond with, “Oh, it’s awesome. There are cars and planes and computers . . .”

Would he have any idea what I’m talking about? Of course not. So he asks what cars and planes and computers are. If I want him to understand, I’d have to use terminology he knows. So I explain that in the future, we’ll have horseless carriages and giant metal birds that fly around with people inside them and boxes that sit on desks and . . . well, I’m not sure how to explain computers in a 16th century way.

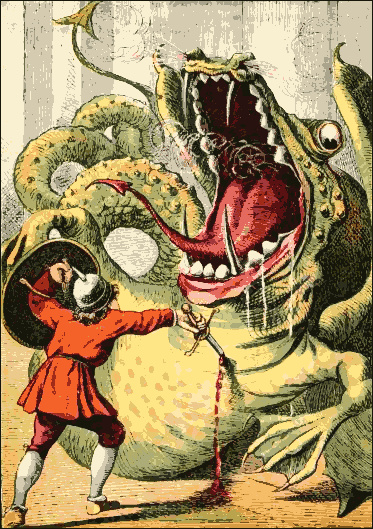

Those examples would help communicate the concept, but not the specifics. For example, when thinking of an airplane, Marty may think of this:

Not exactly what I had in mind, right?

I think something similar is happening here. God wanted to communicate a very specific idea to Ezekiel: a time was coming when His presence would once again be in the midst of His people (notice in Ezekiel 48, the Temple is in the center of the city, which is partitioned for the tribes). But because Ezekiel couldn’t quite grasp the exact nature of this return, God used ideas that he could grasp.

So what was that specific idea? Well, can you think of a time when water flowed out of a Temple (Ezekiel 47)? Here’s a hint: John 19:34.

My theory is that God was trying to tell Ezekiel about Jesus. The problem is that now, people are assuming He was talking about a giant metal chicken.

Wait, I’m mixing my metaphors there, aren’t I?

The point remains: from where I’m sitting, the earthly Temple has been transformed, through Christ, into something far greater than it ever could have been as a stone building. To go back to that single edifice would be like ripping the wings off a butterfly.

Now that doesn’t mean that I don’t think a Temple might never be rebuilt in Jerusalem. There’s a big difference between will and should be. Will it? I have no idea. Should it be? This amillennialist says, “No.” We haven’t needed it for two thousand years and we won’t need it in the future.

This may seem like a lot of dithering over a minor point, but in two weeks, I’ll talk about why this is actually fairly important. When theological rubber hits the road, all sorts of things can happen and sometimes, they’re not that good. So I’ll see you in two weeks. Maybe in video form.

A good, recent example of this is Harold Camping. I know it’s been a little over a year since that so-called “prophecy expert” shot himself in the proverbial foot by wrongly predicting the end of the world not once, not twice, but three times. Now most of us rightly chalked him up as a kook, but the sad reality is, far too many people fell for his schtick. Many of them donated most, if not all, of what they had to help “get the word out” about the impending judgment day. While I can’t find the links now, I know I read a few interviews with true believers who had sold all that they had in order to travel around the country and make sure that the country knew what Mr. Camping had cobbled together using his “holy mathematics.” Now that it’s a year later, I can’t help but wonder where those folks are now. I suspect that a few of them probably did not land on their feet after blowing the life savings on (let’s call him what he is) a false prophet.

A good, recent example of this is Harold Camping. I know it’s been a little over a year since that so-called “prophecy expert” shot himself in the proverbial foot by wrongly predicting the end of the world not once, not twice, but three times. Now most of us rightly chalked him up as a kook, but the sad reality is, far too many people fell for his schtick. Many of them donated most, if not all, of what they had to help “get the word out” about the impending judgment day. While I can’t find the links now, I know I read a few interviews with true believers who had sold all that they had in order to travel around the country and make sure that the country knew what Mr. Camping had cobbled together using his “holy mathematics.” Now that it’s a year later, I can’t help but wonder where those folks are now. I suspect that a few of them probably did not land on their feet after blowing the life savings on (let’s call him what he is) a false prophet.