Preference V. Weakness

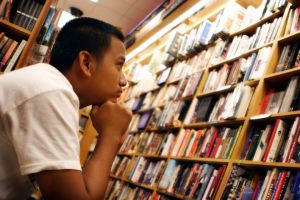

As a reader, I approach stories differently than a friendâlet’s call him Bobâapproaches them. I might know nothing about the author, or only a little about the basic plot, but if the story sounds interesting, I’ll settle in for the ride, just see where it takes me. After all, the adventure is the point.

As a reader, I approach stories differently than a friendâlet’s call him Bobâapproaches them. I might know nothing about the author, or only a little about the basic plot, but if the story sounds interesting, I’ll settle in for the ride, just see where it takes me. After all, the adventure is the point.

Bob needs to know everything up front. He wants to know the end in the beginning. If he goes into a story with a certain expectation of the plot or the outcome, but the story doesn’t deliver it quite the way he wants, it’s a bad story.

On the other hand, my mom is a voracious reader, butâdespite her critical skills at work in financesâshe doesn’t analyze stories much. If they catch her interest and are written halfway decently, she’ll read them to the end. Over the years, there have been stories so poorly executed or so cumbersomely written that she never finished, but those are rare. She says she’s not a good judge of writing, nor is she a literary analyst; she just knows what she likes.

My brother and sister-in-law are similar: Tell them an intriguing story, tell it well, and they’ll go along for the ride, regardless of genre. They have their preferences, but they’ll go outside them for a good yarn.

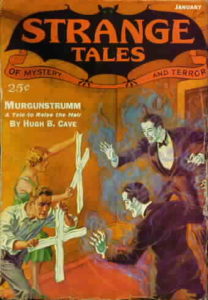

The opposite was true in a writers group I used to attend. Members often declared a story good or not depending on its genre. There were some categories that just weren’t acceptable (horror, for instance), or that were deemed too difficult to understand (science fiction and fantasy), and still other stories (mysteries, say, or modern dramas) thatâregardless of executionâwere considered good.

In that group was the literary world in microcosm: hobby writers and dedicated authors; grammar snobs and grammarphobes; curse-word teetotalers and folks unafraid to add pepper to the pot; poets, plodders, rule-abiders, and rebels. And though they might agree on basic mechanics or general story structure, they could come to verbal blows over the definition of a good story.

Just as soon as someone says, “A good story always _____,” or “A good story never _____,” someone else will present an exception.

Many moons ago, I herded a group of young writers to a one-day seminar, and the instructor set them at ease by demonstrating how simple a story can be to construct:

Basic Story Formula

The 3 Ps

Person – description, desires, friends/family, enemies/antagonists; as the story progresses, include “movie extras” as needed to flesh out the rest of the population

Place – affects person and problem, and can become a character of its own

Problem – what person wants but is prevented from, or finds difficulty in obtaining

Essential Extras

Suspense/Suspects

Secrets – doled out sparingly, and thus keeping the suspense, rather than being dumped all at once

Surprises

Easy, right?

But what about Bob (some of you will get that joke!), or the folks in that writers group I used to attend? They have all sorts of opinions. How is a writer supposed to please everyone?

He can’t.

An author might know generalities about his audience, but he can’t know exactly what kind of reader will pick up his work. Just because it’s military science fiction doesn’t mean only men will read it. Romances are mainly read by women, but not exclusively by women. My daddy read Louis L’Amour westerns, and Mom read Zane Grey. I read about Pippi Longstocking almost as many times as I read about Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn. At school and among friends, we cross-pollinated, talking up the books we enjoyed. We didn’t care about that strange word we weren’t sure how to pronounceâgenre.

Reader differences go far beyond genre or gender. Each person brings his or her own preferences, prejudices, expectations, beliefs, experiences, and assumptions to the story.

Readers who’ve experienced heartbreak or fulfillment, rejection or acceptance, abuse or love, bullying or support, physical difficulties or excellent healthâall will react differently to love stories or adventure yarns or YA novels, you name it.

Readers who’ve experienced heartbreak or fulfillment, rejection or acceptance, abuse or love, bullying or support, physical difficulties or excellent healthâall will react differently to love stories or adventure yarns or YA novels, you name it.

Similarly, readers with an atheist or agnostic worldview will likely filter or perhaps not even select books with a religious worldview. The same is true among religions: readers from one faith filtering or rejecting stories told from the perspective of a differing religion.

One’s opinion of a book often depends on what one expects or wants from it. Some folks prefer a predictable formula, because they want to know ahead of time how the story ends. It makes them feel safe. Surprises are uncomfortable. Other folks want to enter the fictional world blind, learning it as they go. While they might hazard guesses as to the outcome, they enjoy the challenge of making connections and overcoming obstacles alongside the characters. There’s a catharsis in that approach.

Monsters in a romance novel might be unexpected, but that doesn’t mean they don’t belongâdepends on the romance, I reckon. Spaceships in a Western, pixies in a horror tale, ghosts showing up in a children’s storyâthey don’t belong only if the author hasn’t done his or her job. I certainly wasn’t expecting a race of Biblical giants to show up in a suspense novel I read a few years backâand if the book had a weakness, I would say it was the sketchy set-up for their presenceâbut I thoroughly enjoyed the story. Other reviewers disagreed about the giants’ part in the tale, and still others were uncertain as to the science fiction-y-ness of their appearance, but the world of the novel opened the reader to the possibility of such creatures. In that regard, the author did her job.

Monsters in a romance novel might be unexpected, but that doesn’t mean they don’t belongâdepends on the romance, I reckon. Spaceships in a Western, pixies in a horror tale, ghosts showing up in a children’s storyâthey don’t belong only if the author hasn’t done his or her job. I certainly wasn’t expecting a race of Biblical giants to show up in a suspense novel I read a few years backâand if the book had a weakness, I would say it was the sketchy set-up for their presenceâbut I thoroughly enjoyed the story. Other reviewers disagreed about the giants’ part in the tale, and still others were uncertain as to the science fiction-y-ness of their appearance, but the world of the novel opened the reader to the possibility of such creatures. In that regard, the author did her job.

As for a book being dull or exciting, intriguing or confusing, profound or pointless, while much may depend on the author’s skill, much also relies on audience perception. One writer I know thinks science fiction is the domain of teenagers and immature men who refuse to leave their mothers’ basements; therefore, anything I try to share in that genre is not received, no matter how polished and exciting it might be. That’s not a weakness in the genre, just a preference in the reader.

What does the audience expect but not get from a story? And is the omission necessarily a weakness in the story, or just a misapplied expectation?

By expectation, I don’t mean what any reader can reasonably expect of any story: an intriguing premise, good writing, interesting characters, a solid plot. Be they filled with big splashy action pieces or the minute dramas of everyday life, stories must draw readers into their worlds.

That’s why I readâto be taken somewhere elseâbut where I am taken depends on the story itself, and some journeys I’ve enjoyed more than others. Some writers are excellent guides. Even if I don’t relish the journey because the subject matter is difficult, or the ending is less than happy, a skilled writer can lure me down an unpleasant path, and I willingly follow, not because I want to be depressed but because I must know where the path leads. And I’m being led by a writer who knows the way.

On the other hand, some writers need guides themselves, having tangled their plot threads into Gordian knots, or lost their stories through gaping plot holes. I’ve been there myself. Unfortunately, it’s not a typical tourist trap, though the cost can still be high, and, no, it doesn’t come with a t-shirt.

So, what happens when a book doesn’t meet my expectations?

There might be a variety of reasons it doesn’t do so, from poor marketingâthe jacket copy or the cover picture has little or nothing to do with the contentâto a build-up that fizzles out by the end of the book; from weak motivations for character actions to improbable situations (for the world the author has created); from promises made early in the book that aren’t fulfilled later to overwriting (florid detail and emotion, or action scenes that stretch into the ridiculousâand the book isn’t intended as a comedy), or underwriting (so bare-bones that setting and characters are not established), and so on. Those are weaknesses.

Preferences might include a happy ending instead of a depressing one; a character who lives when he should have died; the good guys winning; a certain pair of characters ending up together romantically instead of with other people or with no one; characters making wise decisions instead of bonehead ones. One of my preferences is crisp and clear action/fight scenes; most fights end a lot sooner than Hollywood flicks would have us believe.

If my preferences aren’t met but the story is solid, preferences go out the window. As long as the internal logic of the story holds, and as long as the writer has done his job, then I can still be satisfied with the book, even if I’d rather certain elements of it had been different.

The author is not responsible for my prejudices or preconceptions. Regardless of how well a story is told, readers will approach it with their own points of view. These can either be complimentary to or at odds with the author’s intent. However, whether or not a story’s core is solid and dramatic depends on its teller, and it’s up to us writers to make sure we tell our stories well.

– – – – –

Keanan Brand is a writer and freelance editor, and taught writing to children for fourteen years as part of the after-school program for a community youth center. In his younger years, he also freelanced for a local newspaper, writing human interest stories. Fiction is his first love, however, so he left journalism to pursue creative writing. His short fiction has won awards, as has his first complete novel, which is under consideration with a publisher.

A few years ago, Keanan commented on a post here at Speculative Faith, and it happened to be read by Johne Cook of Ray Gun Revival magazine. Johne visited Keanan’s blog, read some off-the-cuff fiction posted there, and invited him to write for RGR. The resulting science fiction serial can now be read from the beginning at Adventures in Fiction, with episodes posting each Saturday.

In remembrance of Pearl Harbor 1941, thank you to the men and women who served in the military and on the home front during World War II.

âThe Greatest Adventure,â from Hanna-Barbera, also showed a cave stable.

âThe Greatest Adventure,â from Hanna-Barbera, also showed a cave stable.