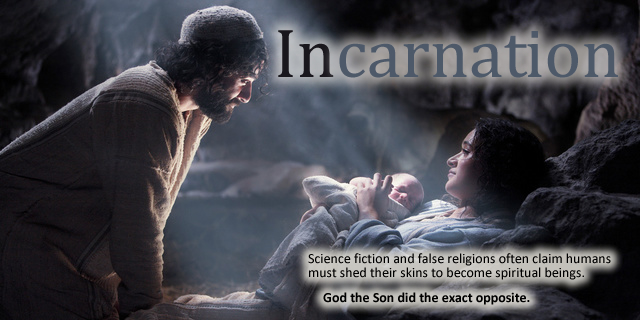

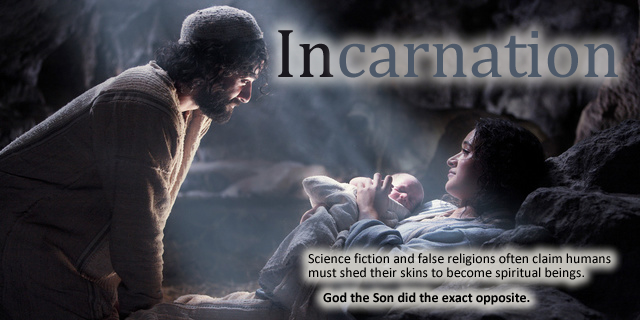

Yes, many science-fiction stories and most false religions â including some Christianity â seem to enjoy flatly contradicting the Bibleâs plotline, only for fits and energy-being giggles.

Scripture says God first saves peopleâs souls or spirits, then their bodies, then the world.

Scripture says God first saves peopleâs souls or spirits, then their bodies, then the world.

Man says that we as âgodsâ ourselves can first save our physical world, then our souls by evolving into some kind of spiritoid entities â ignoring the importance of the body.

Last week, commentator D.M. Dutcher called this âtranshumanism.â And thatâs exactly what it is. Though such beliefs are common to many false religions, the notions we most often see in sci-fi (really theyâre fantasy elements disguised as sci-fi) combine classic humanismâs âarenât humans greatâ posturing â as seen in many Star Trek episodes â and the âone day we will become energy-based spirit beingsâ of New Age and âspiritualâ religions.

Itâs a bait and switch: Yes, humans are great, except for what makes us human.

Now for a more encouraging outlook. Many other stories do honor both the goodness of the physical world underneath the corruption of sin â and more helpfully, honor the idea of a hero who has originated in a higher status and instead deigned to dwell among man.

The most recent example may be the trailer for Man of Steel, the new Superman film series re-launch to release (in the U.S.) on June 14, 2013. If you havenât seen this trailer, behold.

More than other heroes, Superman is often seen in this pose. I wonder why?

Iâm intrigued. It seems the makers are not merely gritty-rebooting Superman. Instead they may be going the direction Iâd hoped, not by angst-ifying our hero â which did drag down the otherwise promising Superman Returns in 2006 â but by assuming that he is a truly good man. How would the world see him? Put off by his goodness, would they reject him?

This is an echo of incarnation: a mighty hero becoming mortal, living as one, to save them.

With that as the filmâs theme, even if not its main theme, the trailer didnât even need to jump right into showing âthe Christ-figure pose,â as author Jeffrey Overstreet observed.

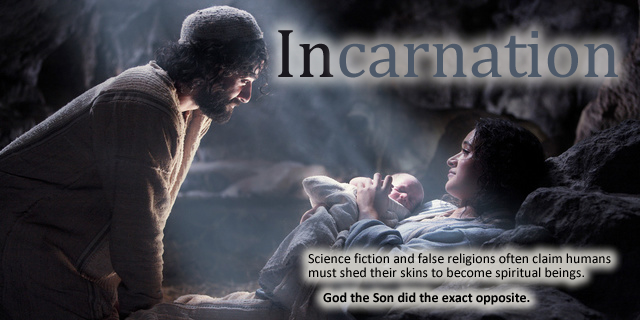

Why does incarnation truth captivate us? How does it inspire real and imaginative worlds?

1. God-become-man is solidly Scriptural.

Christians are bound to accept that Jesus Christ is both God and man. Too many Scriptures confirm both His human origin and His divine nature. Too many heretics have immediately gone for the doctrinal jugular by challenging Jesusâs true humanity (the Gnostics) or His divine nature (the Arians, and also modern-day cults such as the Jehovahâs Witnesses).

For those who love Christ the Hero, we have no reason to doubt His words about Himself or the testimonies of those who met Him. âIn him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily,â the Apostle Paul wrote (Col. 2:9). And we do not accept these words only out of some sense of obligation. If we say we love Him, why would we doubt His self-described origin? Why would we even want to divide His ânatures,â or treat Him only as divine or only as a man?

2. God-become-Man means we can see the image of God.

For some reason, occasionally I get into more discussions about what a âgraven imageâ is and whether Christians can, for example, make a movie about Jesus played by a human actor. Recently someone mentioned that a Nativity scene includes a âgraven image,â versus the second of the Ten Commandments. To that I responded:

If that’s a âgraven image,â so was the Face of Christ, the eternal God made flesh. The fact that Christ was, and remains to this day, a Man with an âimage,â must be taken into account.

Some will say, âWell, that was a perfect representation.â Yet even after He was gone, the disciples would have tried to recall His physical âimage,â and not recalled it âperfectly.â

[A nativity-scene Jesus is] an imperfect representation, [but] based on the precedent of He Himself being made flesh. One must not make a “graven image” of God [the Father] as He is Spirit and should not be reduced that way. However, Christ was a Man, a real Man, and remains so to this day. God all but invites us to imagine Him immediately and personal, while also reminding us of His power, transcendence, wrath, and mystery. He is all of these.

Donât worship an image like this one. But Jesus really was the physical âimage of the invisible Godâ (Col 1:15).

It may be because some people, deep down, doubt that Christ was truly human and the very âimage of the invisible Godâ (Col 1:15), that the apostle John (1 John 4:1) told people to test spiritual influences by asking whether they accepted Christ had come in the flesh.

Jesus is both good and heroic, yet appears âflawed.â Just as any good storyâs hero. This way He is âaccessible.â But thereâs a vital difference: Jesus only seemed flawed. He never sinned.

No, I wouldnât worship a movie-Jesus or a nativity-scene Jesus. I also would not worship a fellow Christian, one who now bears the image of Christ! But if Christ stood before me, I could bow down and fully, unashamedly, and rightfully, with the Creatorâs endorsement, gaze upon His Face and worship a Man.

3. Jesus remains God-become-Man to this day.

This is something we may not often speak about, possibly because it hurts our heads. Yet imagine the encouragement, the wonder! Jesus remains the God/Man even now.

Yes, somehow even in the present-day Heaven that could be an incorporeal realm. Even making intercession before the throne of God (Rom. 8:34). Even standing at the Fatherâs right hand (Acts 7:56). How does He do it? That part we donât know. Which leads to âŠ

4. Our Hero in the flesh is a Biblically true, God-endorsed mystery.

Pastor and columnist Jared C. Wilson phrased it like this:

When Colossians 2:9 says, âFor in him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily,â we know that the fullness of deity dwelled in fertilized ovum.

Will the Empire State Building occupy a doghouse? Will a killer whale fit inside an ant?

And here we are told that omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, utter eternalness and holiness dwelled in a tiny person. This makes Santa coming down a chimney seem a logistical cakewalk.

âThe head of all rule and authorityâ (Col. 2:10) had one of those jelly-necked wobbly baby heads. The government rested on his baby-fatted shoulders (Is. 9:6).

Such a truth strains our corporeal minds. Have you wondered about how this later worked?

- Being fully God, did Jesus keep His omniscience? If so, how could His human mind keep all that knowledge? Or did He choose not to know some things (Matt: 24:46, Luke 2:52, 8: 45-46; or Heb. 5:8)? Was that part of the divine âemptyingâ (Phil. 2:7)?

- Did Christ choose to âturn onâ some divine superpowers, such as watching Nathaniel long-distance (John 2:48), or knowing about the coin in the fish (Matt. 17:27)?

Scripture doesnât tell us how. It only assures us, through Christâs example and in later works of doctrine, that Christ was both fully God and fully Man.

Maybe thatâs why Christmas over other holidays brings a unique wonder. Make no mistake, Good Friday and Easter matter. Yet only during Christmas do we celebrate the fact that, as Isaiah predicted in Isaiah 7:14, the Hero actually became God-with-us, Emmanuel.

Eagles are not kindly birds. Some are cowardly and cruel. But the ancient race of the northern mountains were the greatest of all birds; they were proud and strong and noble-hearted. They did not love goblins, or fear them. (page 99) Is it possible to be great or even noble and not also be kindly? Can true heroes or âgood guysâ have such flaws?

Eagles are not kindly birds. Some are cowardly and cruel. But the ancient race of the northern mountains were the greatest of all birds; they were proud and strong and noble-hearted. They did not love goblins, or fear them. (page 99) Is it possible to be great or even noble and not also be kindly? Can true heroes or âgood guysâ have such flaws?

Imagine if a modern filmmaker had made these kinds of changes, as a âgritty rebootâ of Gollum. What hue and cry might readers have raised? Rather, Tolkien beat any revisionist to the punch, and in a way that demonstrates something I have slowly realized about the classic fantasy author: in many ways, Tolkien is much more of a âmodernâ author than people credit him for â especially fantasy fans who like things classical and serious.

Imagine if a modern filmmaker had made these kinds of changes, as a âgritty rebootâ of Gollum. What hue and cry might readers have raised? Rather, Tolkien beat any revisionist to the punch, and in a way that demonstrates something I have slowly realized about the classic fantasy author: in many ways, Tolkien is much more of a âmodernâ author than people credit him for â especially fantasy fans who like things classical and serious.