Horror Is Based on A Biblical Worldview, Part 2

Novelist Mike Duran continues a two-part conversation to share the stories and themes of his new nonfiction work about Christians-exploring-horror, Christian Horror. (Read part 1.)

Novelist Mike Duran continues a two-part conversation to share the stories and themes of his new nonfiction work about Christians-exploring-horror, Christian Horror. (Read part 1.)

ESB: Often I hear horror critics/skeptics use verses such as Phil. 4:8 and Eph. 5:12 to criticize horror. Horror apologists will often reply with, âWell, the Bible itself includes themes of horror.â But the critics/skeptics then repeat one of these rebuttals. Youâve already discussed some of this at your website, but can you rephrase your challenges to the critics/skeptics?

1) âThe Bible has sparser descriptions than a modern novelist.â

Mike: Probably because the Bible is not a novel. If the argument is that vivid descriptions of biblical events are prohibited, I would ask if that applies to every biblical event or just the gruesome, lurid ones. Should we also refrain from a detailed fictionalization of Moses on Mount Sinai, the Resurrection, or Saulâs Damascus Road experience? If not, then why are the âdarkerâ elements of Scripture avoided and not the âlighterâ ones? Bottom line: The role and intent of film and fiction is a lot different than that of the Bible.

2) âThe Bible is using words, but movies/TV actually show the grotesque thing happening.â

Mike: Thatâs the power of the medium. Conversely, is âshowingâ a good thing tolerable? In other words, showing Jesus healing the Gadarene demoniac is okay, but showing the same man running naked and gibbering through the tombs is not?

Unless weâre arguing that celluloid / digital images are inherently evil, weâre going to run into the typical debate about what images Christians should and should not subject themselves to. You know, Is it OK to watch R-rated movies? and all that.

Itâs one thing to object to movies/TV on the grounds that the medium is inherently evil. But objecting to certain images on the grounds that they are disturbing, provocative, or offensive, opens an entire other discussion, one which involves the subject of Christian liberty and the role of art. In reality, I think that is the discussion more Christians are hinting at when they object to horror.

Furthermore, an argument could be made that Christians should not turn away from looking at evil and darkness. Iâve always loved the quote attributed to famed Japanese director Akira Kurosawa who said, âThe role of the artist is to not look away.â

Our world is full of real-life horrors that Christians should not look away from. This doesnât mean that we should delight in evil, be captivated by the macabre, or celebrate darkness, but that our perspective of the world and the human condition should be unflinching. Watching an exorcism is disturbing. It should be! But if we really believe demons can possess someone and Christ has the power to free them, enduring the horror of the event may be necessary. Abortion, genocide, sex slavery, ritual murder, or serial killings are horrific. But refusal to look upon and think about evil may itself be evil.

In this sense, thinking about âwhatever is trueâ (Phil. 4:8) can serve as a proof text for thinking about horror, not turning away from the vile and depraved. A âtrueâ picture of our world must include its horrors.

ESB: What are the best or most poignant Scriptural examples of horror genre(s) in action?

Mike: Where to begin? Why not at the beginning where a perfect Man and Woman turned from their Creator, unleashing an evil force (sin) upon the earth. Sounds like the basis for a good horror flick, huh? (Man defies warning and darkness falls.) The Fall of Man may be the most horrific of all biblical concepts.

Mike: Where to begin? Why not at the beginning where a perfect Man and Woman turned from their Creator, unleashing an evil force (sin) upon the earth. Sounds like the basis for a good horror flick, huh? (Man defies warning and darkness falls.) The Fall of Man may be the most horrific of all biblical concepts.

On a personal level, Iâve always found Gustave Doreâs âAdam and Eve Driven Out of Edenâ deeply disturbing. The cherubim with âa flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life (Gen. 3:24, NIV) must have been a terrible, majestic thing.

So many biblical âterrorsâ can be traced back this event, namely the Crucifixion where an infinitely holy God, the Last Adam, suffered a torturous death and bore the sin of the world. (Knowing what we now know about Roman crucifixion, itâs not a surprise that Mel Gibsonâs The Passion of the Christ has been labeled âhorrorâ by some.)

In fact, many of our âstandardâ Bible stories contain disturbing and horrific elements. Noahâs Flood, the plagues of Egypt and the Passover (especially the angel of death slaughtering Egyptâs firstborn), Elisha and the prophets of Baal, Saul and the Witch of Endor, the Slaughter of the Innocents, and perhaps the greatest of all, the Book of Revelation with its depiction of cosmological upheaval, plagues, the antichrist, and the Great White Throne Judgment. Perhaps this is why the Horror Writers of America includes the Bible in its canon of horror literature.

ESB: Iâd like to set this one up a little more. Again, on your own site you explored more of this topic. You also dealt with a âshutdownâ verse I often hear: Ephesians 5:12, which says, âFor it is shameful even to speak of the things that they [unfruitful works of darkness] do in secret.â

The skeptic says: âThere you go â you should not even be speaking of works of darkness.â

Again, apologists reply with, âBut the Bible speaks of dark things in a way.â But I think this could reinforce the criticâs false assumption: that weâre bound to write for exactly the same reasons and in the same way the biblical authors write. Instead shouldnât we be challenging that assumption? âWhere in the Bible does it say we are limited to its stylistic choices? Where in the Bible are you getting the idea that merely hearing/seeing a sin described is the same thing as committing the same sin?â And of course, âIf itâs always wrong to see/hear about sin, why make the Bible the exception â and arenât we always singling out specific sins anyway?â

Mike: I agree with you, Stephen. Those who object to horror often import arguments based on a dangerously narrow view of art and culture.

In Christian Horror, I suggest that this traces back to an ultra-conservative Fundamentalist view of the world, one which has led to the creation of a Christian sub-culture. In this circle, holiness is viewed as abstinence from certain images or cultural commodities. Itâs a âtouch not, taste notâ ethic (Col. 2:20-23) that defines holiness in terms of the types of films, television, music, and books we enjoy. Itâs led to an entire class of âprofessional weaker brothers,â those who object to films and fiction based on the number of curse words or sexual innuendoes. Which is why âclean,â âfamily-friendlyâ fare is advocated.

This perspective is unique to evangelicals, as opposed to Catholics who have been historically much more active in and less restrictive of the arts. To me, this entire discussion comes back to our theology and how it influences our perspective of art and culture.

ESB: What do you hope Christian Horror will do for fans, readers, and the Church as a whole?

Mike: All I’m really hoping to do is continue a conversation thatâs been going on for a while about the Church and culture. As an evangelical, and as someone who traffics in evangelical fiction circles, I think weâre missing some great opportunities to grow and employ cultural mediums with more savvy and effectiveness; to expand our vision for artists and the arts. My entire thesis in Christian Horror is that not only is the horror genre compatible with a biblical worldview, but that I believe Christian artists should be at the forefront of reclaiming it.

Sure, thereâs a lot of junk in the horror genre. But that same critique could be said of other genres. What we should acknowledge is that horror can also be a powerful medium. For me, this is the conversation I hope to continue.

Godspeed, Mike. You can read a preview of Christian Horror or purchase the book on Amazon.

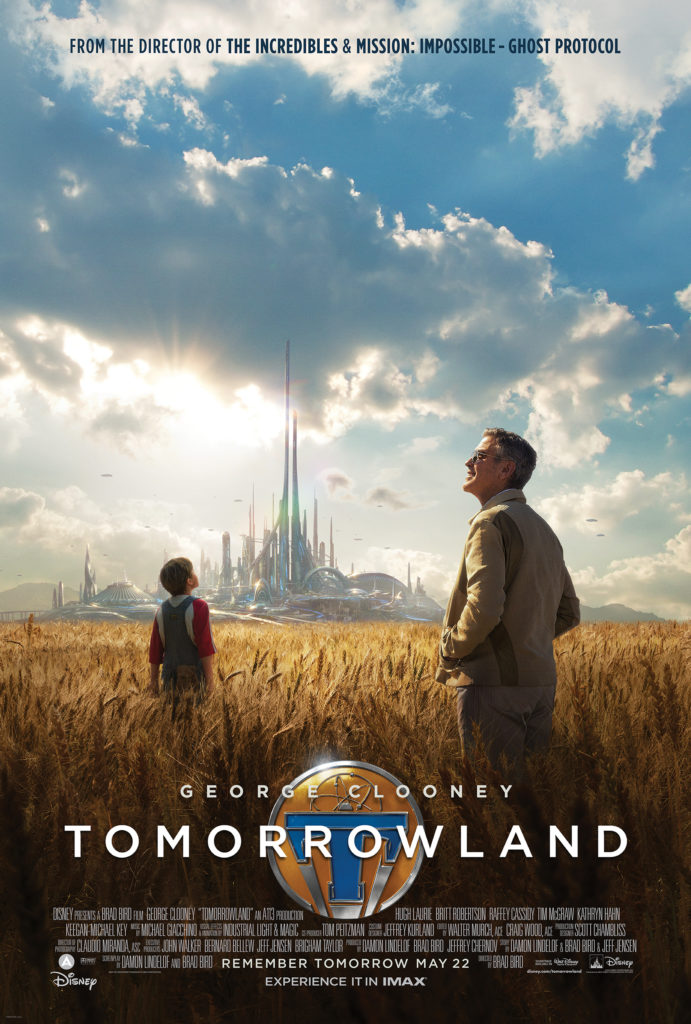

A mysterious pin. Being suddenly transported to an open field, a shining city of the future rising up in the distance. And of course, the promise of a hopeful message derived from the legacy of the man who sparked that famous quote, âWe keep moving forward, opening new doors, and doing new things, because we’re curious and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.â

A mysterious pin. Being suddenly transported to an open field, a shining city of the future rising up in the distance. And of course, the promise of a hopeful message derived from the legacy of the man who sparked that famous quote, âWe keep moving forward, opening new doors, and doing new things, because we’re curious and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.â I know why the critics dislike it. I know what it is theyâre referring to when they call it âjudgmental.â From the very start,

I know why the critics dislike it. I know what it is theyâre referring to when they call it âjudgmental.â From the very start,

![[Citation required.]](http://www.speculativefaith.lorehaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/excerpt_nervouswitch.jpg)

In reality, horror elements occur in many fantasy novels and films. Peter Jacksonâs Lord of the Rings trilogy contains many horrific images: the Ring Wraiths, the Dead Army, and Saruman (portrayed fittingly by horror film veteran Christopher Lee), just to name a few.

In reality, horror elements occur in many fantasy novels and films. Peter Jacksonâs Lord of the Rings trilogy contains many horrific images: the Ring Wraiths, the Dead Army, and Saruman (portrayed fittingly by horror film veteran Christopher Lee), just to name a few.

A shadowy force is manipulating the neighborhood’s underworld, and until he finds a way to stop them, all of his efforts are in vain. The main person controlling these elements is ruthless crime lord Wilson Fisk.

A shadowy force is manipulating the neighborhood’s underworld, and until he finds a way to stop them, all of his efforts are in vain. The main person controlling these elements is ruthless crime lord Wilson Fisk.