Iconoclasm, Part 1

What’s right with the Reformation?

With all the imagery saturating the Scriptures, I had to ask myself, why is there such lack of aesthetic understanding and development in the Evangelical Church? I found a partial answer in the iconoclasm of the historical period called the Reformation (16th century). The Reformation simultaneously freed art from its captivity to the religious dogma of immanence, but also constrained it to a new dogma of transcendence that would influence Protestant theories of art and beauty until the present day.

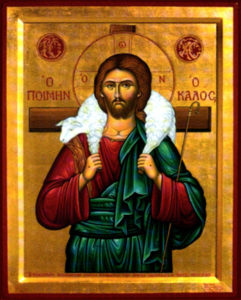

By the time of the late Middle Ages (1300-1500), the Roman Catholic Church was the dominant religious force of the Western world. Around it’s heart and soul of worship had developed a very immanent visual culture. That is, spiritual relationship with God was mediated through physical objects and the senses of the worshipper. This immanence stressed God within the created order, not in a pantheistic sense, but certainly in a sense of imparting grace or redemption through visible objects. Relics of alleged pieces of saint’s bodies or fragments of the holy cross were housed in shrines with altars which the faithful would make pilgrimages to see because, as William Dyrness notes, “these objects not only reminded worshipers of supernatural reality but actually became a detached fragment of God’s power.”1 Images of Christ and the saints, called “icons,” became important theological tools of teaching the illiterate as well as objects of veneration.2

By the time of the late Middle Ages (1300-1500), the Roman Catholic Church was the dominant religious force of the Western world. Around it’s heart and soul of worship had developed a very immanent visual culture. That is, spiritual relationship with God was mediated through physical objects and the senses of the worshipper. This immanence stressed God within the created order, not in a pantheistic sense, but certainly in a sense of imparting grace or redemption through visible objects. Relics of alleged pieces of saint’s bodies or fragments of the holy cross were housed in shrines with altars which the faithful would make pilgrimages to see because, as William Dyrness notes, “these objects not only reminded worshipers of supernatural reality but actually became a detached fragment of God’s power.”1 Images of Christ and the saints, called “icons,” became important theological tools of teaching the illiterate as well as objects of veneration.2

Medieval mystery plays, passion plays and miracle plays were also commonly used to instruct the peasants and celebrate feasts, festivals, and holy days through liturgical drama. Churches were huge, glorious edifices full of wood and stone statues of the Virgin, saints, prophets and martyrs; paintings of everything from the birth of Christ to his resurrection adorned the walls; stained glass windows depicted the “stations of the cross.” Dyrness concludes, “The medieval believer before 1500 took it for granted that the human relationship to God and the supernatural world was visually reflected and mediated through this visible order of things.”3

But like the brazen serpent, this mediatorial art became more than engaging, it became enslaving in the eyes of a new breed of Christian, the Reformer. Men like Martin Luther, Huldreich Zwingli and John Calvin saw this visual culture as distractive at best, and idolatry at worst. Zwingli described the slavish devotion that parishioners would engage in before these images:

Men kneel, bow, and remove their hats before them; candles and incense are burned before them; men name them after the saints whom they represent; men kiss them; men adorn them with gold and jewels; men designate them with the appellation merciful or gracious; men seek consolation merely from touching them, or even hope to acquire remission of their sins thereby.4

The cult of relics and images was vehemently preached against by the Reformers, and the people repented – with acts of vandalism and destruction of these images in churches throughout the land. Even though the Reformation leaders condemned this vigilante iconoclasm as illegal and immoral they could not control it as it got out of hand.5 But iconoclasm, rather than being an elimination of visual culture, was really more of a replacement of one visual culture of immanence with another visual culture of transcendence.6

If immanence stresses God within the created order, transcendence stresses God’s otherness or separation from the created order. If immanence is more physical or sensate, transcendence is more abstract or mental. So it was transcendence that was the new focus of Reformers like Calvin, who “privileged the ear over the eye” by elevating the written and preached word over the visual image as God’s superior means of communication.7

In all this logocentric zeal, leaders like Zwingli and Calvin never disparaged visual art used for “secular” purposes. Their focus was on images used in worship, not all art whatsoever.8 In fact, what occurred was a liberation of the arts from the religious stranglehold it had on people. As Michalski puts it, until the Reformation, “art had been imprisoned in grand ideological and religious systems.”9 Because of the Reformed belief in the priesthood of believers rather than a priesthood of elite religious authorities, all of life, not merely church life, became sacred. And that included the arts. The distinction between secular life (family, work, leisure) and sacred life (Church, prayer, Scripture) dissolved.

Martin Luther was strong in his denunciation of the secular/sacred dichotomy:

The idea that the service to God should have only to do with a church altar, singing, reading, sacrifice, and the like is without doubt but the worst trick of the devil…The whole world could abound with the services to the Lord, not only in churches but also in the home, kitchen, workshop, field.10

The Reformed concept of nature being God’s “second book of truth” through which his glory is reflected led to the origin and development of the famous 17th century landscape art of the Dutch Netherlands.11 Reformed artists like Albrecht Dürer are credited with being major influences on the origin of landscape painting, something that was considered without much merit until this paradigm change.12 After all, creation itself glorifies God as his handiwork of beauty, so why wouldn’t a simple landscape do so as well as an altar piece of the Last Supper?

In a sense, Protestant iconoclasm gave sacred significance to “secular” subjects and experience. It made the whole of life religious, not merely church life. Conversely, it also “secularized” art, that is, it brought art out of the parameters of religious cult objects and transferred it into the domain of aesthetic beauty apart from ecclesiastical use. It was the theological foundation of the liberation of the arts.

(Next Friday, part 2: The Bible is full of fantastic imagery; how do Reformation-minded Christians often ignore this?)

- William A. Dyrness, Visual Faith: Art, Theology and Worship in Dialogue (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Baker Books, 2001), p. 34. ↩

- William A. Dyrness, Reformed Theology and Visual Culture: The Protestant Imagination from Calvin to Edwards (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 21. ↩

- Dyrness, Reformed Theology, 26. ↩

- As quoted in Margaret R. Miles, Image as Insight, p. 99. ↩

- Sergiusz Michalski, The Reformation and the Visual Arts: The Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe (New York, Ny.: Routledge, 193, 2005), p. 74. ↩

- Dyrness, Reformed Theology, 6. See also, Margaret Miles, Image as Insight, pp. 122-123. ↩

- Ibid., 6. ↩

- John Calvin Commentary on Genesis, Vol 1, Genesis 4:20. (Albany, OR: Ages Software, Version 1.0, 1998); Michalski, The Reformation and the Visual Arts, p. 71. ↩

- Michalski, The Reformation and the Visual Arts, p. 194. ↩

- Martin Luther, accessed February 5, 2008, at <http://www.xristos.com/Pages/Quotes_page.htm>. ↩

- Reindert L. Falkenburg, “Calvinism and the Emergence of Dutch Seventeenth-Century Landscape At” in Paul Corby Finney, Seeing Beyond the Word, pp. 343-351. ↩

- Gene Edward Veith, Painters of Faith: The Spiritual Landscape in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2001), p. 21. ↩

When I was in London, our tour guide stopped by several cathedrals, including Westminster. My first response was “God is great and we are tiny,”–one thing that I think is communicated better by massive artwork than statistics. But I hadn’t considered the differing emphasizes–God’s presence versus transcendence.

Thanks for your insightful article. It is strange to me that we, though hundreds of years removed, continue to use terms like “reformed.” I suppose it is helpful as a heuristic. But I also wonder what word we will use for the Christians who ultimately decide to depart from the modern reformed church?

“Reformed” today tends to be a more educated-sounding word for “Calvinist.” Modern Calvinists, of which I am one (though I have some Lutheran theology too) take Calvin himself, and the other Reformers of 450 years ago, very seriously, and read and study them more than they do modern theologians–since everything since the Protestant Reformation is more or less dirivative, or, in the case of critical theologians (who don’t accept the Bible as divinely inspired) destructive, of biblical faith. The Protestant Reformation is seen as a major hinge point in Christian history–hence a thorough understanding of its progenitors is seen as very important…even though it is hundreds of years ago.

Lest you think we are incredibly anachronistic, just as any modern philosopher who doesn’t grasp the major contributions of Plato or Aristotle (who lived thousands of years ago)…is considered 2nd rate at best, so too amidst scholars who hold a high view of scripture–knowlege of our roots in the Reformation 450 years ago–is considered vital.

Fascinating!

My first time in continental Europe was in Bern Switzerland. The medieval cathedral there was–in Zwingli’s day–converted to a Reformed Protestant Church, and has beautiful architecture, but, inside and outside is more blank and sad than a tomb. The main museum in Bern has the original pre-reformation images in it (unearthed, literally, in the 1980s), and admittedly they are ridiculously gaudy (and poorly executed art too–Bern was kind of backwoods in 1520). I understand the Reformers’ reaction to the corruption of Renaissance Roman Catholicism, which with images sometimes did ammount to idolatry, but the wholesale iconoclasm–particularly by the Reformed Calvinists, was tragic.

The Luthern approach, though not perfect, I believe was MUCH more balanced and biblical, when it came to the arts. I think it is no coincidence, that the great 18th Century Classical composers came out of the Lutheran and Roman Catholic world, NOT that of the Reformed/Calvinists. Even though music in worship was not sanctioned by Calvinism like the visual arts–still, disparagement of one area of human creativity effects the whole.