Tony Breeden on Story Evangelism

Should Christian stories evangelize?

Since I’m both a preacher and apologist on the one hand and a sci-fi author on the other, I get asked this question a lot. Typically, it’s a young Christian struggling to do the right thing with the gifts and talents God has given them. We’ve been given the Great Commission. The Bible also says to do everything we do as unto God Himself,1 after all, which would certainly include how we enjoy our fiction as Christians. On this, we can all agree.

How exactly we carry out these Scriptural mandates as readers (and writers) is where we start to differ.

First and foremost, we have to decide what we mean by Christian fiction. This matter alone is hotly debated.

Christian fiction or fiction by Christians?

There are those that believe that there should be something distinctly Christian about our fiction (what we might call overt Christian fiction) and others who affirm that Christian fiction is simply fiction written by Christians (passive Christian fiction, if you will).

There are those that believe that there should be something distinctly Christian about our fiction (what we might call overt Christian fiction) and others who affirm that Christian fiction is simply fiction written by Christians (passive Christian fiction, if you will).

Some of those who hold to a passive view of Christian fiction claim that anything a Christian writes will necessarily be written from that Christian’s worldview; that is, the Christian’s worldview will necessarily shine through even if that material is not overtly Christian. After all, in the realm of nonfiction Christian literature, the book of Esther never once mentions God and yet it manages to convey His providence, right?

But in my experience, the idea of an intrinsic worldview in our fiction is more truism than truth. The person who holds to this view of Christian fiction tends to craft his writing in such a way that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy; however, Christians can be utterly inconsistent and we’ve all read fiction that was so secular that we were surprised to later discover that the author was a Christian.

This brings up an important point: Christian fiction is as Christian as we make it to be. The Christian element is intentional. If we wish our fiction to be recognizably Christian in any sense of the word, we will have to want authors to write it so on purpose.

One the other hand, if your view of Christian fiction is simply a synonym for excellent craftsmanship, so be it. As a preacher, I would remiss if I didn’t point out that you certainly have a Biblical precedent for your position and, more importantly, the Bible says absolutely nothing about how to outline, write and edit fiction.

To draw a parallel, Christian comedian Tim Hawkins says that when he’s asked about Christian comedy, he responds, “I mean I’m a Christian and I do comedy, but Christian comedy doesn’t really make much sense to me. I mean, there’s no Christian plumbing.” This resonates with what Martin Luther said about Christian shoemakers: “The Christian shoemaker does his duty not by putting little crosses on the shoes, but by making good shoes, because God is interested in good craftsmanship.” John the Baptist gave similar advice to Roman soldiers and tax collectors.2

Prescriptive vs. descriptive

For those who wish to read overtly Christian fiction, we have the further question, also hotly debated, as to whether we ought to enjoy fiction that accurately describes Christians and the world we live in or fiction that is prescriptive of how things should be. Questions like, Should characters cuss? Should sex scenes be explicit or off-camera, so to speak? These days, the lines are generally drawn between authors adhering to CBA/EPCA publishing standards and those who don’t think authors should sanitize things quite to that extent.

The latter camp may safely point out that the Song of Solomon contains pretty graphic sexual references and the Bible is full of graphic violence throughout, particularly in the Old Testament. They can also support their bid for edgier Christian fiction by the fact that the Bible includes the gross character flaws of its human heroes. Granted, we’re dealing with fiction versus nonfiction here, but if Christians do not look to the Bible for a precedent, whence shall we look? Descriptive Christian fiction has the added benefit of telling stories of real people with real problems that a real Savior can remedy rather than what often comes across as a sanitized alternate universe where non-Christians live in a society where Christian morals are observed almost without fail.

Goober, Barney and Floyd conduct a seance in “The Andy Griffith Show.”

If I may be frank, we live in a reality where even Christians often fail to live that way. We certainly don’t live on “The Andy Griffith Show,” yet Christian books of the prescriptive type are written as if the Hayes Code were a requirement for Christian fiction. The protagonist tends to be a believer or gets saved somewhere in the book, typically with no learning curve. They also tend to include what I call plastics: characters who are role models or paragons of an ideal type of Christianity in much the same way and extent that Barbie dolls reflect an ideal type of the female physique. Real people have problems. Real Christians aren’t always able to quote exactly the right Scripture or give exactly the right argument at exactly the right moment. Real Bible believers have doubts from time to time. Even the most zealous Christians can have pet sins and vices. Bad things happen to good people. Even our best evangelistic efforts may be met with indifference rather than acceptance or rejection. The Psalms testify that the bad guys don’t always get their earthly comeuppance.

The reason for the plastic alternate Earths of prescriptive fiction is that Christian fiction of the CBA/EPCS stripe is intended for a Christian audience AT LEAST; that is, they hope that non-Christians read their books, but their primary audience are the folks who make up the bulk of their sales: Christians. Safe plastic worlds filled with plastic role model Christians are the least likely to offend Christians and relate experiences that might cause them to sin vicariously, as it were. That Aslan (as a type of Christ) was good but not safe is oft-quoted; what is not often discussed is that safe fiction does not necessarily equal good fiction, especially since good fiction challenges us in some way rather than catering to our ghettoism. Likewise, we may write Christian fiction that isn’t safe that is nonetheless good. God is not safe; why would He ask us to write safe fiction?

Evangelical vs. edifying

I’ve said all of that to say this:

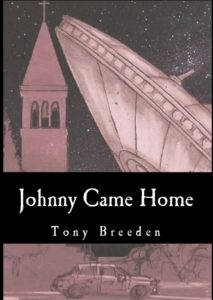

The trouble with storytelling, as far as Christian fiction is concerned, is that all stories have a message. If an author has written a book well, there is a message or moral that every reader is supposed to come away with. For example, the message of Johnny Came Home is that who we are is not determined by our genetics or our upbringing but rather by our actions. Christians realize that stories have messages and morals so a lot of us insist that Christian fiction should deliver a Christian message. There’s a lot of Biblical precedent for this. Nathaniel told a story to illustrate King David’s guilt. Jesus taught in parables, which are essentially teaching stories.

The trouble with storytelling, as far as Christian fiction is concerned, is that all stories have a message. If an author has written a book well, there is a message or moral that every reader is supposed to come away with. For example, the message of Johnny Came Home is that who we are is not determined by our genetics or our upbringing but rather by our actions. Christians realize that stories have messages and morals so a lot of us insist that Christian fiction should deliver a Christian message. There’s a lot of Biblical precedent for this. Nathaniel told a story to illustrate King David’s guilt. Jesus taught in parables, which are essentially teaching stories.

The question then becomes whether these stories should deliver the Gospel or whether it’s OK to simply edify. I find it ironic that those who write prescriptive CBA/EPCA fiction tend to be the ones who insist that we need to use Christian fiction to evangelize. I find it ironic because plastics and CBA/EPCA fiction are better suited to edify the Church than to evangelize the lost. Follow me here: Prescriptive Christian fiction offers us an ideal of Christianity. It says, Look, here’s what a Christian ought to look like. Here’s how a Christian could effectively live and share their faith. See? You can do it too! The trouble with it is that it delivers role models in an unrealistic alternate Earth, making us wonder just how effective it is as a tool for edification. At best, it seems a better tool for the reinforcement of USAmerican evangelical cultural expectations. Propaganda for the stained-glass Sunday school version of Christianity that supposes Jesus turned water into grape juice and that the Song of Solomon is about our relationship with Christ.

Which brings up my biggest objection to prescriptive Christian fiction: If CBA/EPCA standards were applied to all Christian literature, it would condemn huge sections of the Bible. Think I’m overreacting? Read the last chapter of Judges and get back to me. Shouldn’t the moral standards of our Christian fiction at least be consistent with the revelation of the Christian Sourcebook? Granted, we wouldn’t read such passages to children, but we aren’t supposed to remain children. Prescriptive fiction is meant to provide Christian audiences with a safe alternative to secular fare so that they don’t have to exercise discernment much, if any at all. How is this a good thing for a church that exists amidst an increasingly non-Christian world?

Descriptive Christian fiction is potentially better suited to evangelize. It presents the world as it is, warts and all, just as the Bible does. When such a story connects those problems to the Solution, it has the chance to more effectively resonate with unbelievers. A real solution for real problems. The questions, I suppose, is whether non-Christians ever really read Christian fiction. In other words, are we just wasting our time? I’m really not sure how we can know that. One plants, another waters, but God gives the increase. One thing we can be sure of is that descriptive fiction is a better tool for edifying believers who live in the real world with all its real problems.

To preach or not to preach?

Of course, the question is not whether Christian fiction should edify, but whether it should evangelize?

We all have a mandate to evangelize; we are ambassadors for Christ. We are commanded to do everything as unto God. These points are indisputable fact. Nevertheless, we also realize that we do not overtly proselytize in everything we do. We do not feel compelled to spell out “Jesus Saves” in our alphabet soup. Despite all claims to the contrary, a cross or fish on your car does not evangelize so much as it advertises your brand: you’re a Christian. Don’t get me started on Christian breath mints.

As I noted at the beginning of this essay, there is a legitimate Biblical precedent in just doing a great job in your profession. Some folks think that’s not Christian enough. My response to that as a preacher is, “Who are you to judge another man’s servant? To God alone is a man justified.” This position is perfectly fine from a Biblical standpoint. Luckbane, the first book in my Otherworld series, follows this philosophy.

There is also a Biblical precedent for message-driven Christian fiction. Jesus did it, as did prophets of old. I did it in Johnny Came Home, which is essentially an action-packed book of descriptive apologetics fiction about superheroes trying to figure out where they came from while they save the world. The choice to write message-driven evangelistic fiction does not give us an excuse to produce inferior literature. Ephesians 6:7 and Colossians 3:23 still apply to authors who wish to evangelize through their fiction. If we’re going to read well-written Christian fiction, we need to eschew the CBA/EPCA model of prescriptive fiction in favor of a more realistic descriptive storytelling that accurately describes the world with all its problems, so that we can enjoy fiction that resonates with more readers and shows how the Gospel is relevant to those problems.

So should Christian fiction evangelize? It’s not Biblically imperative, but if you do, do it right.

Should Christian stories evangelize?

This is a crucial issue for anyone who loves stories but loves Jesus more, and wants to glorify Jesus through our enjoyment of stories or our making of stories.

During October our new SpecFaith series explores this issue.

On Thursdays, reviewer Austin Gunderson and writer E. Stephen Burnett host the conversation with interactive articles. On Fridays and Tuesdays, guest writers such as novelists and publishers offer their responses to the question.

We invite you to give your own answers to the #StoryEvangelism conversation.

Excellent stuff here!! I loved your point about how our Christian fiction will be as Christian as we make it, and it has to be intentional, but it’s also fine to just focus on the quality of our craft, just like any other artist or worker in the world should as Christians. We’re not preachers, after all – we’re writers. We called to evangelize, because we’re Christians…but we aren’t called to any kind of special evangelism above and beyond the call to Christians who don’t write books. “Who are you to judge another man’s servant?” is definitely the right verse for this topic.

I also loved this: “I find it ironic that those who write prescriptive CBA/EPCA fiction tend to be the ones who insist that we need to use Christian fiction to evangelize. I find it ironic because plastics and CBA/EPCA fiction are better suited to edify the Church than to evangelize the lost.”

So true.

Thank you for sharing. I appreciated your insights and your engagement with the topic. It really is complicated at times to define and explain, and, often, as a Christian writer, I feel as if I am torn in two directions in terms of telling a good expectations and the expectations/restrictions within the CBA market.

But, in my opinion, the best point is that if we do it, we are to do it right. Because otherwise, we turn Christianity into a punchline and give people even more reasons to steer clear. Which is sad and unfortunate.

Thank you again. Have a wonderful day!

“If we’re going to read well-written Christian fiction, we need to eschew the CBA/EPCA model of prescriptive fiction in favor of a more realistic descriptive storytelling that accurately describes the world with all its problems, so that we can enjoy fiction that resonates with more readers and shows how the Gospel is relevant to those problems.” I agree and disagree with this in the space of a breath. Maybe I take to task the “need to eschew,” rather than then entire statement because the CBA provides a central place for readers (or buyers) to choose “safe” materials to read.

At the same time, I agree. It is a hard task to find quality books/novellas which appeal to my genre in the CBA. As my teenager usually says (after I search and find a CBA book she may like), “It was okay.”

I found this quote on the ACFW forums and I have it saved to remind myself that I’m not the only one who feels this way. It’s directed towards YA, but it applies here:

“I think the perception of today’s kids is that Christian Fiction is their great-grandmas’ reading material. We need YA that can excite youth, and most of them go to public schools. They have required reading for English that may be shocking, depending on the agenda of the teacher and/or English dept.” – Nike Chillemi

While I write overtly Christian in my current WIP, I see the flip side of the coin. I’ve read poorly written “this character represents Jesus” books, and I suspect I will read more in the future. This post was a fabulous read and I’ve shared it with my writers group. Nothing like a hot topic to get the synapses firing!

Sarah,

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. My first novel was overtly Christian, as I mentioned. I set out to write the sort of books I would like to read. Unfortunately, I wasn’t really finding this in my local Christian bookstore, which is CBA for the most part. Bear in mind, I’m a guy. My favorite Christmas movie is Die Hard [no lie]. I’m pretty easy to please, but as a fan of Firefly, LOTR, Jackie Chan, Star Wars, Sherlock Holmes and the MCU, you can imagine what sort of fiction interests me… and how precious little of it gets published by the CBA industry. Alas!

I strongly feel that an industry dominated by CBA standards have produced and even encouraged poorer quality storytelling so long as the book is [more or less] doctrinally sound. That criticism spills over into Christian film, which holds itself to a similar standard. Not all of it. But the trend seems to be increasing. Your teens recognize the difference in quality; however, to be clear about my “eschew” comment, I’m not advocating an abandonment of appropriate material for appropriate ages. I just think the CBA standards aren’t the way to go about it.

Regards,

Tony Breeden

“you can imagine what sort of fiction interests me… and how precious little of it gets published by the CBA industry. Alas!” Ah…my type of statement!

Funny that this blog hit last week and Steve Laube has a post today about fiction proposals which mentions “unique story” hooks. He goes on to say: “The editor then said, ‘Where is the originality? They all start sounding the same.”

I couldn’t help but think of this blog post and your points. I haven’t written something similar and haven’t been able to turn a head in my general direction because of it. I’ve been asked if I can make it more contemporary (no) or romantic (no).

Your comment about recognizing quality? Spot on. Lord willing, more quality AND diverse books will grace the CBA.

On a practical level, a good evaluative question to ask is, “Does this make the story suck (or whatever your preferred synonym)?” (Bonus, it can be applied to almost every other choice you could make about writing.)

If the evangelism slows down the pacing and/or makes your characters seem like pod-people, it’s most likely a bad decision. But if your pace was already slow and your characters already like pod-people, do not pass GO, do not collect $200.