When Christians Vacate An Industry

“Roy Rogers was a Christian who was not ashamed to witness for his Lord.”

At some point, Christian involvement in the film industry, in government, in speculative fiction, at least in the general market, faded into near non-existence. I suspect there are a number of other industries we could name that have followed the same pattern. The point here is that when Christians vacate a profession, it necessarily takes on qualities that contradict a Christian worldview.

How could it be otherwise?

The Christian worldview is built on grace and forgiveness. People who have not experienced God’s grace and forgiveness have a different paradigm under which they operate. Sin still enslaves those without Christ, and sin will surface.

As I may have mentioned in an earlier post, I’m watching the H&! All Star Trek reruns of all the Star Trek spin-offs. I love those shows. I love to compare the different Vulcans and different “evil races” and the different captains. I love the character development and the plot twists and the heroic, self-sacrificial attitudes and actions. But missing from the Star Trek universe is Jesus Christ.

Yes, there is a kind of Buddhist pantheism and there is a Hindu like religion, but the primary god of the Star Trek productions is human kind. Sentient beings are revered above all else, as is the right of each to choose for him or herself what he or she is to be and do.

None of this surprises me, and it doesn’t dissuade me from watching the programs. I don’t expect to find Christianity in Star Trek. Don’t misunderstand. I do find truth in Star Trek, so there are times when these different programs say something perfectly in sync with the Bible. But those are more apt to be the exception than the rule.

The point is, for the most part, Christians didn’t write the Star Trek episodes. As a result, Christianity simply isn’t present in the stories. I don’t recall a single reference to a church, to the Bible, or to the cross, and not to Jesus. It’s as if the future world the the Federation the Star Trek creators imagined had outgrown Christianity as it had violence.

The absence of violence is quite funny, actually—the star ship Enterprise roams the galaxy ferreting out new life and new civilizations, all in the name of peaceful exploration, though they’re armed to the teeth with photon torpedoes and phase cannons and all kinds of other weaponry.

So no violence and no Christianity. But weapons and other religions.

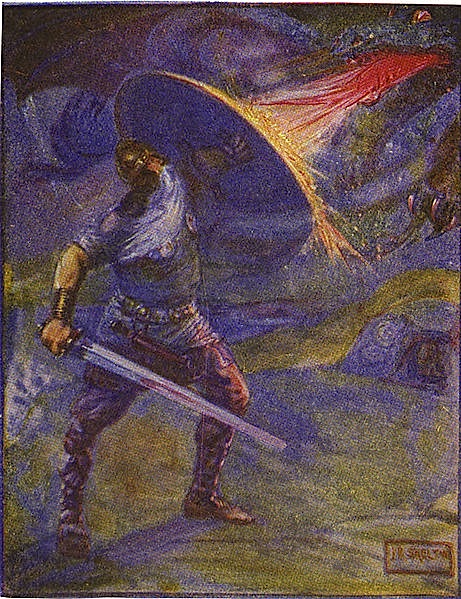

The same is true of literature. After C. S. Lewis we have Phillip Pullman, and after J. R. R. Tolkien we have Gorge R. R. Martin. Why? What happened to the “spiritual atmosphere” of an ancient story such as Beowulf?

The same is true of literature. After C. S. Lewis we have Phillip Pullman, and after J. R. R. Tolkien we have Gorge R. R. Martin. Why? What happened to the “spiritual atmosphere” of an ancient story such as Beowulf?

I suspect scholars argue over why, but I don’t think there’s any denying the fact that Christians moved out of the storytelling industry, and more specifically, out of the speculative fiction industry. But when Christians vacate, that leaves non-Christians.

All this to say, it’s time believers make a concerted effort to reenter the speculative fiction industry. Christian writers have made great inroads. Enclave Publishing specializes in Christian speculative fiction, for instance, and Bethany House continues to be traditional Christian publisher that produces quality fantasy. Many Christian authors have gone the route of independent publishing, and a few have dipped their toes into the general market.

In other words, believers are pushing open the door to speculative fiction (just as others are trying to push open the door to the film industry). But I think it’s worth asking: what do we hope to accomplish?

Are Christians entering the realm of speculative fiction for no other reason than we like to stretch our imagination?

“Values he embraced throughout his life – hard work, love of country, love of family, love of community and most of all love of God.”

Clearly, in life, the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian isn’t sinlessness. So why should sinlessness drive our fiction?

But the opposite, which seems to be gaining traction—show the world as it is—brings us back to the question: what is the distinctive of a speculative story told by a Christian? Is there a difference? Should there be a difference? If so, what is that difference? If not, isn’t that simply just another way of vacating the industry of Christian influence?

Love this!! I was just telling someone the other day that Christianity is largely absent from the artistic/literary world…the church is not involved with those things and doesn’t care about them much. I would love to see more and more people pushing into the mainstream arts as Christians…not just hanging out in the Christian artistic sub-culture.

I agree. The problem is that the church doesn’t support the arts as we once did. My church is (thank God) different in this matter, but the problem still exists. I want to write books like C.S.Lewis did which entice non-Christians as well as shore up believers, I have a church that has joined me on this mission and in every mission that I have brought to them and I pray that other churches will change to reflect that the arts matter.

Technically, the brick and mortar church never did. It was up to individual believers to act according to their gifts.

Not sure you are entirely correct there. The Pope sponsored Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine Chapel, for example. Much of medieval art would not exist without the sponsorship of the church.

Tamra said, “As they once did.” That would include art from Europe in the Middle Ages where almost everything was religious.

I do think it’s one thing to say we need more Christians to be involved in the general market and it’s entirely another thing to see it happen. Ah, for the days of patronage.

And the question remains: what is the distinctive we want from our creative endeavors? Would readers be surprised to learn that a particular novel was written by a Christian? What sets our work apart from that of someone who is not part of the family of God?

Becky

I hear a lot more talk about the need for Christians to be involved in the arts in a meaningful way, but often the idea is that church should include more artistic expression. I think Christians need to enter the public arena with our art, but the problem is that many are afraid their Christian worldview will not be accepted, so they hide their candle under a basket.

Becky

I think it was CS Lewis who once said that what the world needs is not more Christian writers but writes who are Christian. I tend to agree.

Uhhh, that’s “writers”.

I also agree with that quote. But it’s often used to argue against enjoying stories or artworks within a distinctly “Christian” culture. If so, then I would disagree with that. As a Christian, what I need is often a “Christian writer,” not just a Christian who writes. Sometimes “the world” also needs this.

I agree, Stephen. If a Christian writes the same story that a non-Christian writes, I don’t think it matters if we are or are not in the publishing arena. The point is, our stories should communicate, and in some way they should communicate something different from the stories everyone else is writing.

Becky

–I suspect scholars argue over why, but I don’t think there’s any denying the fact that Christians moved out of the storytelling industry, and more specifically, out of the speculative fiction industry. But when Christians vacate, that leaves non-Christians.

I’ve come across this type of thinking before, but this time I want to kick against it a little.

I’m simply not prepared yet to accept the notion that “Christians moved out of the storytelling industry”, at least until some kind of solid evidence of this moving out can be given.

Since Jimmy Stewart’s picture is prominent at the end, what about looking at what is likely his most famous movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life”. True, the movie has angels, it has a star-like being that could have been God talking to another star-like being called Joseph, it had some praying.

I would say that “It’s a Wonderful Life” is a movie that was strongly influence by religious and even Christian views and ethics, but I’d have a harder time accepting the notion that it is a Christian movie, no matter how loosely one used the word Christian.

Other examples could be given. What about a much-beloved TV series like “Little House on the Prairie”? A series that had a lot of religious stuff in it, but can it really be called Christian? To put that question in a few other ways to try to clarify what I mean, what was shown to be mankind’s problem in LHotP? What was the solution? When God is mentioned, or Christ is named, how does that happen? Is Christ portrayed as our savior who sacrificed Himself for our sins, or our friend who gets us through difficult times?

Audie, you seem to be making the case. If these are not Christian, then doesn’t that prove the point that Christians moved out of the storytelling industry?

More later.

Becky

If they moved out, they first had to be in.

And I am trying to note a difference between “Christian” and “Christian-like”.Entertainment has had a good bit of “Christian-like” stories, as noted above. These stories may have had fairly good and uplifting messages, taught good morals and ethic, but didn’t exactly represent orthodox Christianity or added strange or cute things to it (“Every time a bell rings, an angel gets its wing”).

OK, I understand your point now. I guess I was thinking further back. I think what you’re describing is what I consider to be part of the leaving process. Instead of telling stories with truth about the spiritual, we accepted myth as if that was the same thing! Then the myth even faded, and there was little more than cultural behavior that resembled Christianity. Pretty soon that was gone too, and I think that’s were we are now.

But how do we change things? I don’t think we can go from no Christianity in stories to stories infused with the gospel—sort of zero to sixty in zero seconds. It can’t work.

But what would work?

I think about R. J. Anderson’s second middle grade book about a boy whose parents were missionaries. It’s actually a story about fairies, but the protagonist brings his background with him. And his doubts. It’s a great example, I think, of a writer bringing spiritual questions, or a “spiritual atmosphere” into the story. I think that might be the best way to start.

Well, I guess I would first have to ask, what do we mean by these types of stories working?

If by “working” we mean getting lots of people to read them and agree with them, then we may be asking a lot, even too much.

If anything today is epidemic in the church, it is the changing of the message of the church to draw people in, to essential make the church’s message a big “bait and switch”, to talk about all kind of things that are suppose to be considered “relevant” and then sneak in some Jesus-talk along the way.

And it would be naive to think that the message has not change. Evangelism has been replaced with notions like changing the world and even taking over the world, conversion has become life change and improving your life now, and there are so many versions of the gospel–prosperity gospel, health and wealth gospel, dream destiny gospel–that we might wonder what most people in churches really believe.

Here is one support for the notion that the church is far more of a mess then even professional nay-sayers might think.

http://lifewayresearch.com/2016/09/27/americans-love-god-and-the-bible-are-fuzzy-on-the-details/

This is the fruit of the church’s attempts to entice the world with a nice-sounding message.

So, if we want to go into spiritual messages and spiritual atmospheres in stories, we need to think about it in a much firmer way then we have so far. Perhaps it could work, but has this done such a good job so far? If it can work, how should it be done? Is referring to God is oblique and indirect ways good enough, or will it lead to a confusing message? If it can work, what kind of storytelling skills does a writer need to develop in order to make it work?

Audie, to avoid the content space shrinking further, I’m going to try replying to my last comment, in hopes that it will still be positioned properly. We’ll see. 😉

By “work” I mean that our stories can again be infused with gospel truth. Right now such stories are simply not acceptable to general market publishers (according to one agent). I don’t think we can get lots of people to agree with them necessarily. But if we write well, people should be willing to read them. Christians read all about the the force and loved the world of Avatar with its false god. People will read or watch good stories, and if done well, they might even think about the world we present, and the gospel that is present.

But I think that’s a long way off. People are becoming more and more openly hostile to Christianity.

I agree with you that the gospel has become confused and confusing. There is much that passes itself off as Christian that simply is not.

I agree that we should not try to entice the world with nice sounding messages—just choose Jesus and all your problems will go away. It isn’t true to experience, and yet people become quite angry at God or the church when their lives involve suffering or disease or the loss of a loved one.

I also agree that we should go down deeper, is how I think about it, rather than presenting a surface Christianity that doesn’t answer the big questions.

So I guess that’s what I think should be our starting place. Rather than creating a story that presents the gospel (especially one that presents it in a superficial way or, worse, in a false way), perhaps we should be writing stories that counter the lies our society is believing today. Lies such as, Man is good. Or there’s nothing after this life. Or this life is meaningless (apart from the pleasure and happiness each person derives from it). Or, here’s the big one, life didn’t just happen.

These are such fundamental issues, and I suspect most Christians don’t realize how radically different the average person apart from Christ views these things when contrasted with the person who has been redeemed by the blood of Christ.

I think this kind of story is “tilling the soil” so that the gospel can one day take root. Because if someone believes that humans are all good, then clearly there’s no need of a Savior. There’s no belief in a who God punishes sin, because that’s Just Wrong to punish innocent people who just make mistakes unintentionally.

I could go on, but I think you get the idea. Those are the types of stories I think Christians can write, that the general market publishers might be open to publish (because the “you can do it, just look inside yourself for strength” stories are becoming cliched), and that readers will read without being offended by someone’s “preachy message.”

Becky

American churches attract one Type of person and don’t seem to know what to do with others when they darken the doors.

They attract predominately extroverts, high in conscientiousness, low in openness, low in sensitivity to painful emotions. Most artists are the exact opposite of this Type. (Like me. Only I’m an ambivert.) No wonder there are so few Christian writers and artists.

When you fail to fit the mold going to church can be lonely. C.S. Lewis disliked going but forced himself to attend. I do the same.

Well, there was a point where there were two really prominent Christian writers in fantasy, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien. That might allow us to imagine that Christians once dominated the genre of fantasy, but that’s not true. There were plenty of other writers of fantasy who were not particularly Christian or who were even anti-Christian.

And in science fiction, the situation was even worse. Jules Verne was not especially Christian and H.G. Wells was very clearly an atheist. While there have been some Christian writers in science fiction for a long time, the genre was almost completely dominated by non-Christians from day one.

So yes, I think Christians should be more involved in writing, but the idea that Christians vacated speculative fiction is simply false. We were never that much involved with speculative fiction in the first place–though we can and should be.