Two Kinds of Heroes

What if someone had done a scientific study on real-world heroes and tried to define what their essential characteristics are? Would it be useful to you as an author to know how heroes actually act–real heroes? That’s what this post is about, a study that found two distinct personality types among soldiers who performed heroic actions during wartime (note this post is significantly edited and adapted from a something I wrote for my personal blog over a year ago, travissbigidea.blogspot.com).

The study I read was based on surveys of World War II veterans, including both “ordinary” vets and those who had been highly decorated for valor. The purpose was specifically to determine what the relationship was between leadership traits and heroism, with the presumption that the WWII survey results would be broadly applicable to heroes in all wars. It may not in fact be true that a study based on WWII would apply to all wars–but I don’t see why it wouldn’t. (Note also this study was based on interviews with United States WWII vets only). The study did find, as I imagined the people who created it expected, that veterans who described themselves as “strong leaders” were more likely to have received a reward for valor than those who did not describe themselves that way. This could be explained in a number of ways, but perhaps the simplest way would be to observe that a certain measure of risk-taking is required to be awarded a medal for valor and that military leaders probably engage in risk-taking more often than people who feel now particular inclination to lead. So this result of the study didn’t really surprise me at all or catch my interest.

What did catch my eye is the fact that among those who won awards for valor, while they in general shared in common a self-description as being good leaders, they otherwise were of two distinct personality types.

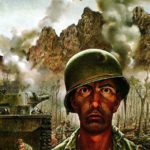

Russian Army WWII heroes. Image credit: Russia Beyond

Note again that both eager enlistees and reluctant enlistees were better leaders than average according to this study. Yet one was eager to fight and kill and the other was not.

These types of heroes appear again and again in fiction in various ways. Achilles was the eager enlistee as a warrior, even though his enthusiasm for war with Troy wasn’t high–while Hector better matches the reluctant warrior, who is forced to fight because of actions of others. While Tony Stark went through various hardships and does in fact show some empathy and self-sacrifice, Iron Man is much more the risk-taking eager enlistee than the other way around. Steve Rodgers was eager to enlist, but he was motivated by self-sacrifice primarily, therefore Captain America is not really a risk-taking personality.

Image credit: Business Insider

So when looking at this study, don’t get hung up so much on the labels of “eager enlistee” and “reluctant enlistee.” I suggest the more important difference is concerning inner motivations. The “eager” hero isn’t any more empathetic than average–but is much more risk-taking. The “reluctant” hero isn’t more risk-taking than average–but is much more empathetic and self-sacrificing. It’s in fact possible to be a reluctant risk-taker (though that isn’t normal) and an eager self-sacrificer (again, not normal, but happens).

For the readers of this post, have you seen any similar studies? Do you know of other motivations for heroes other than the two I’ve mentioned in this article? Have other examples you’d like to add? If so, please mention them in the comments below.

Frodo Baggins would definitely be a reluctant enlistee.

Not your typical hero.

Agreed!

Actually I somewhat disagree about Captain America. He’s still highly empathetic, but he’s more of a risk-taker than otherwise. Even when he was skinny, tiny Steve, he still picked fights he knew he would lose to defend other people rather than, like, call the cops or talk it down or something less risky. And defying governmental authority and the Slovenia accords is pretty darn risky.

I’m curious if risk-taking and empathy don’t occur together as much as (your summary of that) study implies. Do we have Soras who are empathetic risk takers (optional: critical-thinking skills of a bag of wet yarn), or is real life split between vainglorious douches and good but uninspiring eggs?

PS: This is also why I don’t think soldiers or cops deserve an automatic respectability card. They’re not good people just because they’re soldiers or cops, like that Coast Guard guy who was making plans for a mass shooting. Or the large, nonzero number of cops who are white supremacists.

My rule for people is that I give all of them at least a teeny tiny drop of love and respect, but I also am not willing to let them hurt me. Like, I have boundaries, don’t trust anyone entirely and take everything they say with a grain of salt. Most people don’t like it, but it’s better than frolicking through life getting hurt because I was trying too hard to make them feel trusted.

I wish that attitude wasn’t as unusual as you make it sound. But authoritarian culture doesn’t believe in boundaries, and authoritarian culture isn’t as dead as I’d like it to be.

Well, I know people don’t understand boundaries and violate them a lot. That’s precisely why I talk about enforcing boundaries in the first place (and mention that people hate it when I do.)

I think the Captain America movie shows Steve Rodgers fighting out of principle rather than for the thrill of it.

But yeah, it’s certainly possible to combine risk-seeking and selfless empathy, at least I think so. I could perhaps be a little like that myself.

Well, there would probably be the chars that were sort of born into combat, like a lot of Naruto chars. Not all of those chars were reluctant about fighting, because to some learning to be a ninja was just the natural course of their life. Shikamaru, for example, was super lazy and chose to be a ninja partly because his father was a ninja and it was probably just the normal course, but partly also because it seemed like the easiest option for him to make money. But, as time goes on, he grows closer to his teammates and becomes passionate about protecting Konoha, especially after certain events in his life (like losing his sensei).

Chars like Kiritsugu are kind of a blend of both heroes you mentioned. His childhood dream was to be a hero of some sort. But, he was still a happy, carefree kid and didn’t seem to be anywhere near jumping into a battlefield until his entire town perished. After that, he apprenticed himself to an assassin partly because he was an orphan, and partly because he saw it as an opportunity to be strong and prevent further tragedies in the world. After that…he remains an assassin for a mix of reasons. He hates the atrocities he commits, but sees it as his only way to help people at the time. It’s also the main thing he’s good at, so it probably felt only natural for him to continue on that course.

Something seen a lot, especially in anime, are chars that endure something horrible and thus choose to enter combat to deal with it. They weren’t an eager enlistee from the standpoint that they didn’t ask for horrific circumstances to push them toward fighting. But, they are eager from the standpoint that they choose to fight to get revenge, fulfill their personal morals, reobtain something they lost, etc. Often enough, their heroism might be unintentional along the way. Like, they might end up with a close friend and look out for that person throughout the story.

One aspect of heroism which fascinates me is how, among military veterans as well as the ‘everyday’ heroes such as police, fire, emergency responders, and the like, is that when asked about their ‘heroic’ deeds, they so often respond with “I didn’t do anything special, just what needed to be done” (or similar words).

Yeah the study I mentioned judged heroism by medals for valor awarded. I imagine plenty of those guys didn’t consider themselves heroes.

What about heroic actions outside of war?

I am presuming the same personality types would apply.

I think another way to look at ‘risk-taker’ Tony and ‘reluctant recruit’ Cap is that Cap does what is good for the sake of good- no matter what; his story arc is learning just how high a cost ‘no matter what’ is- but sticks to it. Tony does what is good at first for the risk- and becomes good doing it; his story arc is learning to do good even as he starts to hate the risks.

Team Cap all the way, though.

Yeah I definitely like Captain America better myself…