Stop Hating on Christian Popular Culture

Tacky shirts, unbiblical “clean” rules, ripoffs: Christian popular culture can be annoying.

After all, Christian popular culture (or subculture) may not be creative or original. Instead it may sound like the generic brand at your grocery: “If you like Kraft® Macaroni, try me!”

But you know what’s more annoying? A counter-culture against Christian popular culture.

From podcasts to articles to books to comments, you can sense the annoyance: Christian culture is lame. Derivative. Worthless. Out-of-date. We feel a need to counter it all the time.

In fact, that’s the reason I’ve come to dislike constant criticism of Christian popular culture: it’s one counter too many. In order: 1) We have “secular” culture. 2) Some Christians dislike it, and make counter-culture to counter it. 3) Then other (often younger) Christians dislike that, and sort of make a new counter-culture to counter the Christian counter-culture.

That’s too many counters and too much stuff that is made not as much for a purpose, but against a purpose. This doesn’t help, especially when the point of culture is to cultivate: using our God-given talents to make new things, reflecting His beauty, goodness, and truth.

So why do many Christian critics dislike Christian popular culture?

- Unbiblical rules. They find fault with the culture’s unbiblical notions, such as absolute rules against violent content, bad words, escapism, or certain theological beliefs.

- Associations. They associate Christian subculture with the unlikeable or even abusive personality of a particular individual or organization, or with some real harm.

- Bad quality. They grow older, find many praiseworthy things about other popular cultures, and can’t help seeing how much “their own” culture lacks by comparison.

- Bad evangelism. They don’t believe Christian subculture has done much good to show Christ to the world, or to show the world a better picture of Jesus and/or His Church.

Many readers (and contributors) of SpecFaith would agree with some of these criticisms. That’s why, when we see that the Family Christian Stores chain of retail locations is closing down, we feel mixed emotions. We regret to see part of a Christian culture end, while also lamenting what could have been—or hoping for the rebirth of better Christian fiction.

However, if you don’t like the subculture you’re given, shouldn’t you be trying to make a better alternative—just as the Christian counter-culture makers have been trying?

Among Christian culture critics, I don’t see that happening. Instead I see:

- Unbiblical rules. Critics develop an unwritten “code” against, say, Thomas Kinkade paintings or Amish romances. Technically, this isn’t legalism. But if we hear about a person who likes these things, the instant we judge that person, yes, that is legalism. Meanwhile, Christian culture critics can also develop “legalism” for the stories they do enjoy: e.g. the story must have diverse casting, must deal with this social issue in this way, must be well-reviewed by proper critics, must be a cultural thing that is trendy.1

- Disassociation. Critics reject their cultural-fundamentalist belief that you must cut off and separate from worldly friends. But the critics may then turn around and practice a similar separation from their (older?) Christian friends “trapped” in the subculture.

Bad denials. Critics ignore or reject even the truly good elements of the subcultures and stories and music they once enjoyed. But in fact, Christians got very good at many things, including original popular music (especially in the ‘90s) and audio dramas. Some of our animated series were quite good too. Remember the “Adventures in Odyssey” animated videos? Remember “VeggieTales” (which broke creative ground in all sorts of ways)?2

Bad denials. Critics ignore or reject even the truly good elements of the subcultures and stories and music they once enjoyed. But in fact, Christians got very good at many things, including original popular music (especially in the ‘90s) and audio dramas. Some of our animated series were quite good too. Remember the “Adventures in Odyssey” animated videos? Remember “VeggieTales” (which broke creative ground in all sorts of ways)?2- Bad evangelism. Critics accept a false premise of some Christian culture creators themselves: that “all this stuff ought to evangelize (or morally improve) people.” Instead of questioning this false premise, they expect the T-shirts and derivative bands to have helped save their friends (or at least kept us from feeling weird near those friends).

All that aside, the severest challenge to Christian subculture critics is this:

I don’t see them really trying to make better Christian popular-culture themselves.

Many Christian culture makers have at least tried to construct something.

Many Christian culture makers have at least tried to construct something.

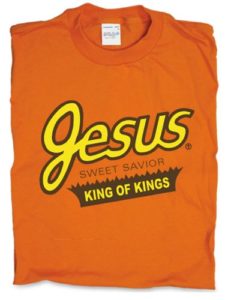

Even the Christian movie-makers construct something. Even the makers of the orange T-shirts with letters spelling “Jesus” instead of “Reese’s” construct something.

Meanwhile the constant Christian-culture critics may prefer deconstructing things.

Or they spend their time only analyzing secular films and finding reflections of Jesus in them, or at least reflections of good family values such as anti-racism/diversity/community in these stories. (And aren’t these “family values” the same as Christianity anyway?)3

Ultimately, Christian-culture critics miss what should be the point of that popular culture.

We shouldn’t have expected it to make Christians look awesome. (Brothers and sisters, we are already worshiping a dead Jewish man with superpowers. Get used to the strangeness.)

We shouldn’t have expected it to save our non-Christian friends or preserve America.

We shouldn’t have expected it to always be creatively excellent, or to always avoid any kind of derivation (however shallow and lame) from the real world of logos and brands.

And we shouldn’t have expected it to be free of the silliest ideas Christians come up with—though often for well-meant reasons—such as codes against certain words or themes.

What we should have and still should expect of Christian subculture is this: to reflect the creativity of the people who make and enjoy it, for the glory of God.

Again, that’s what God wants us to do by making culture in the first place.

God gave us the ability to make things so we could cultivate and construct, not deconstruct.

And many Christian culture-makers, despite some products’ lameness, often did just that. In fact, some of them did the very thing we keep saying we want to do: instead of cursing the darkness, they lit candles. Now, in response to some of their less-bright ideas, are we capable of attempting the same? Or can we only curse in the dark at their dripping wax?

- For some Christians who pursue culture, and/or popular culture, this approach can become a sort of “gluttony of delicacy” or vanity. Lewis’s demon Screwtape suggests this as a way to disguise the sin of gluttony: Screwtape thinks humans assume gluttony is only about excess, but in fact we can also be gluttonous by insisting on tiny portions, or else by only wanting the most elitist kinds of foods. I wonder if some Christians who fancy themselves, say, above commercially successful cartoons or superhero movies, may act like vanity-gluttons in a way geeky fans may act like excess-gluttons. ↩

- A few internet listicles prove Christian-subculture nostalgia is alive and well, such as this one and this one at Buzzfeed and this one at Relevant. ↩

- Or else the stories the critics do create aren’t popular. Even today a cheesy movie like God’s Not Dead 2 can still own church audiences. Meanwhile, a “hipster” sort of Christian movie that employs novelties, such as bad words, barely makes it to a streaming service. ↩

Sometimes it feels like there’s nothing better out there, though. If standard pop culture is a cheese tray and Christian pop culture is a fruit tray, but all the fruit is small or not ripe or just off (like someone putting apples next to oranges, ugh), then I’m gonna still complain if I wanted a desert bar…

man that’s a weird image but I’m going for it anyway.

Yeah. Gimme cheesecake!

I dislike much of the Christian sub-culture, but I do hear what you are saying. Sometimes I think that those who rail against the tacky Christian culture are doing it because it’s just not “cool”…but somehow I don’t think that Jesus meant us to be “cool”. Something about “if the world hated me it’s going to hate you too.” I’m not just pointing the finger outwards, it’s pointing back at me, too. I have to fight against that desire to “fit in” and be accepted. But bottom line is that Christianity IS weird to popular culture, and if it isn’t, we’re just not doing it right. I just wish we could be “weird” for all the right reasons.

Amen to that. I grew up in the heyday of Christian Pop Culture and while I loved some parts of it (Odyssey, Veggietales, Early Bibleman) I was never crazy about the rest. I could never put my finger on why a lot of Christian stuff drove me nuts, but it’s as you and Julie said: something was off (sometimes it was theology related, though). I can’t stand a lot of Christian kids media in particular, for the reason that I feel like our kids deserve better than what scholcky, cheesey, badly animated fare is available today and in the past. I am not maligning the creators, though. I know they are doing their best, but I feel like something is missing. No, Jesus didn’t put us here to be “cool” but he did put us here to tell his story. And sometimes that story is obscured by the fact that everyone wants “quality Christian entertainment” but nobody’s willing to put the time, love, care, and money into doing it. My brother and I and some of our friends are trying to change that. We’re just a bunch of kids, but I know we can kick things into high gear eventually.

I appreciate the blog criticizing the critics. I also appreciate one distinction that you make. The idea of a lifestyle that glorifies God as opposed evangelism as a work (I do hope I haven’t misconstrued your article). Taking the good news of the Gospel of Christ to the world is not a suggestion, it is a command, but using guilt to goad people into action is never good. Evangelism is the natural outcome of putting the goodness of God on display for anyone that is interested to see.

Jon Acuff, I believe, had on his “Stuff Christians Like” list this sad truth: “Christians like to throw other Christians under the bus.” That Buzzfeed video last year was the epitome of this: “I’m a Christian, but not…” I’ve certainly been guilty of this. It all goes back to Jesus’ parable of the Pharisee and Tax Collector. We’re so desperate at times to reach culture that we think we have to apologize for everyone or everything else in Christian culture that doesn’t meet our standards. Whether that’s a standard of excellence, particular theology, moral codes, social sensitivity, I think the rut we get stuck in is thinking there’s only one way to engage and reach people.

There was a great interview with Alex Kendrick where he said, “I don’t know that we’ll be able to hit every target audience,” and explained how Sherwood Pictures primarily focuses on a churched audience vs. a secular audience. Importantly, he owned their style without criticizing that of other Christian filmmakers. I’m reminded of Jesus’ disciples, who in Mark 9 told of their encounter with a different kind of follower: “We told him to stop, because he was not one of us.” And so Jesus sets the record straight: “Whoever is not against us is for us.”