‘Enoch Primordial’ Soup

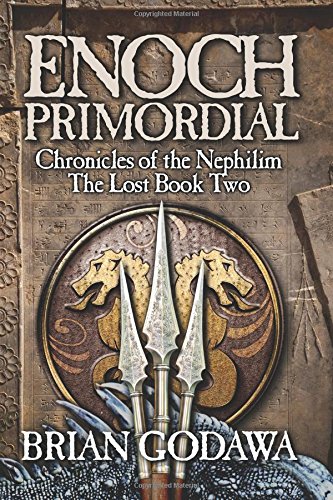

Enoch Primordial — the first installment, chronologically speaking, in the Chronicles of the Nephilim series — is an embellished retelling of the Book of Enoch, that apocryphal document which purports to describe the antediluvian world and is quoted briefly by Jude in his epistle (Jude 1:14-15). As a basis for a speculative take on an era glossed over by a few maddeningly-opaque verses in Genesis, the Book of Enoch is perfect: it fairly bursts with colorful characters and names both familiar and strange, and gets totally explicit about things the Bible leaves vague.

As told by novelist and screenwriter Brian Godawa, the story of Enoch begins with the titular hero serving as counselor to a Mesopotamian puppet-king beholden to the despotic Nephilim — gigantic offspring of human women and a cohort of fallen angels, or Watchers, now posing as gods on earth. At this time, the knowledge of the One True God has seemingly deserted creation: men worship a false pantheon, unaware that the historical monuments which could point them to the truth — the remote Garden of Eden and Tree of Life — have been counterfeited to reflect a revisionist narrative. But when messengers of Elohim appear to Enoch in a vision, the course of his life — and that of his son, Methuselah — is forever altered. What ensues is a lot of running and fighting and encountering of strange beasties.

So far, so good. Cool concept, cool setting. But now we come to the execution.

The structure of the plot is largely episodic. This by itself isn’t bad; what’s annoying is the repetitiveness of the episodes. Enoch, like Abraham his eventual descendant, is called by God to desert Mesopotamia and head off into the wilderness. But his flight from tyranny is fraught with so many “certain death” situations that the phrase itself is stripped of all meaning. Dei ex machina — whether river-current reversals or blade-wielding, wisecrack-attempting angels from heaven — never fail to come through in a pinch. The characters are even reduced to joking about it, Methuselah promising his crush that the next time they face “certain death,” he’ll declare to the world his true feelings for her. I simply can’t think of a more efficient method for deflating all anticipatory tension while heading into the next purportedly-terrifying encounter.

And while we’re on the subject of romance, it must be noted that the novel has much to say in that regard — most of it seemingly distilled from James Bond flicks. The adolescent eagerness, the sheer availability of the novel’s women is breathtaking. You can almost hear them panting after their men, who seem positively frigid by comparison. And it’s enabled by the rest of the cast! When Methuselah and his lady-love first lock lips, “everyone [around them] moan[s] with romantic longing.” When Methuselah and his wife get it on after escaping yet another monster-of-the-week, his son and daughter-in-law take the lusty noises emanating from the bushes as a cue to start swapping their own cringe-worthy innuendos, complete with baby-talk nicknames. After all, what better way to dispel the gravity of a harrowing abductee-rescue than a heartfelt exclamation of “I will never take you for granted again, my dear, dear Pednapoodiums”?

While I respect Godawa’s attempt to portray sexual oneness in marriage as a thing to be desired, the results are less than attractive and often laughable. This is largely due to what I believe is a failure on the part of the novel to realistically portray women.

Now, I’m no feminist, nor do I have much use for critical feminist theory. But I am capable of peering around the edge of a two-dimensional character, and it does strike me as non-coincidental that, of the three women featured in the story (the wives of Enoch, Methuselah, and Lamech), all are drop-dead gorgeous, unswervingly supportive of their husbands, and (apparently) astonishing in the sack. As if to drive home this stereotype, two of them even share the same name! The younger two are tenacious warriors — a trait that, while supposedly unusual for women in-world, comes across as a given.

Sure, Lamech’s lady Betenos is initially distinguished (apart from her name) by her skepticism of Elohim’s sovereignty, but that potentially-interesting roadbump gets predictably leveled within a few short chapters: “[Methuselah’s wife Edna] could hear Betenos breaking down in her protestations … [and] knew it was only a matter of time before Betenos rejected her pagan upbringing and embraced Elohim.” After this, the sole remaining barrier to Betenos’ total conformity — a tragic-backstory-fueled distaste for marriage — is soon overcome by the revelation, through a sorcerous misadventure, that feminism is of the devil. Fortunately, Lamech is on-site to provide an intoxicatingly potent dose of male-headship-philosophy and everything turns out okay. Whew.

And without getting overly spoilerific, I’d like to observe that the ratio of female-to-male protagonist deaths in this novel is astronomically high. As far as the plot’s concerned, the women really are expendable. Take that as you will; I take it as evidence that the women were plot-extraneous characters to begin with — necessary only inasmuch as they provided for genealogical continuity.

But those are relatively minor concerns. Stylistically, the novel has more pervasive issues, at the root of which is its tendency to tell, not show.

This is apparent within the first few pages. Surprised at the depth of exposition to which I was exposed in the novel’s prologue, I tried to console myself with the vain assurance that, well, it was a prologue, after all. Sometimes prologues are like that — sometimes they’re appropriated as landfills for numbing-yet-necessary data that’d otherwise encumber a brisk narrative. But surely, I thought, when we got into the real meat of the thing this kind of arbitrarily-POV-hopping, no-context-left-behind omniscience would get phased out.

Alas, it was not to be.

At its least awkward moments, Enoch Primordial aspires to a Silmarillion-like faux-historicity. At its low points, however, it feels like a textbook that obsesses religiously over the old educational adage “Tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em, then tell ‘em, then tell ‘em what you told ‘em.” You know how authors will often rehash basic plot and character details in each installment of a series for the benefit of those readers who can’t be bothered to start with Book One? Well, to me it felt like this novel was employing that tactic in every single chapter — not just with places and plot-points, but with characterization as well. I lost track of how often, whether through blocks of text or prepositional asides, I was re-informed of things as basic as a character’s history, abilities, or state of mind.

To be fair, some of the characterization was fairly complex. The central protagonists — Enoch and Methuselah — embody, respectively, the seemingly-contradictory ideals of holiness and passion. This intergenerational conflict between heavenly-minded father and earthly-minded son is probably the most interesting element of the story, which is to say that it has the most potential to squander. We learn nothing about either character through observation or experience; instead, we are told what to think about each by an insufferable pedant of a narrator. Their traits, thoughts, dreams, and personal histories get repetitively declared to the reader, who, if he’s like me, struggles mightily to care.

Worst of all, the dichotomous perspectives on life held respectively by Enoch and Methuselah contribute nothing of import to the larger plot. Had their character profiles been surreptitiously switched by some well-meaning miscreant during the writing process, not much would’ve changed in an external sense (in fact, it might’ve been more interesting to watch an earthly-minded Enoch struggle to accept the reality of heavenly visions). What these characters believe, while obviously important to them, has but little effect on the bigger picture.

But back to storytelling technique. How do we know that Methuselah’s a hedonist? Why, we’re told as much in a matter-of-fact tone. Do we get to watch him appreciate nature, gorge on good food, crack dirty jokes, or lech after beautiful women? No. But we are told that he does all those things. Well … okay. If the narrator says so. I guess.

Conversely, how do we know that Enoch’s an ascetic? Not through any actions on his part, that’s for sure. The closest we come is by watching an argument he has with his son over dinner (during which both conveniently perceive their relative excesses and easily repent). But how do we know? Do we spend long hours with Enoch in prayer? Are we made to feel his revulsion at the base impulses sated by those around him? Does his yearning for paradise seem to us as close and constant as the blood in his veins? Are we alarmed at the widening distance between himself and his son? Not in the slightest.

As a general rule, we do not witness events; we are advised that they occur. The cumulative effect is that of a story delivered second-hand. It’s a narrative distance that discourages the reader’s emotional involvement.

One of the casualties of this tell-don’t-show approach is description. Now, I’ll confess here to being a bit of a description-junkie. Nothing attracts me more to a fantastic story than a carefully-cultivated atmosphere and vivid word-painting deft enough to avoid bogging things down. I want full sensory engagement when reading speculative fiction, and that’s often an unreasonable demand. But, even taking my prejudices into account, it remains a fact that adequate description encompasses more than mere place-names. The reader must be able to inhabit a fictional world; anything less and the work might as well be delegated to the map in the front.

So when a crucial new item is introduced, I expect to be given enough clues to at least visualize it on my own. Describing it as “a multi-bladed weapon called a sword, which did not just cut but spliced [sic], diced, and shredded” is simply inadequate. It leaves me floundering for the remainder of the story to conceptualize what on earth this thing looks like and how it could possibly function as an element of the protagonists’ “spinning, twisting, flipping,” Hollywood-standard-issue combat style.

Ironically, the novel’s descriptiveness flags despite prolific modifiers. Adjectives and adverbs accumulate in drifts, presenting the reader with an appearance of solidity while consigning him to sink in abstraction. The modifiers, not being concrete, don’t lend themselves well to visualization. Take this sentence for example: “Enoch and Methuselah, with gaping mouths, watched the two girlish bodies undulate in an ebb and flow of lascivious sensuality.” It’s a sentence that contains a lot of words, some of them fairly large, but little actual description. Bear in mind that the male characters here, being under the influence of a seduction spell, aren’t capable of assigning negative value judgements to the female characters’ antics. So adjectives like “lascivious” exist solely in the purview of the narrator. What’s happening is that the reader’s being told how to think about what’s happening without first being told what’s actually happening.

The vast bulk of the novel’s descriptions are non-concrete. Consider another example. During a scene in which Methuselah is literally tracking his wife via scent, we are informed that “Edna’s husband loved her so madly that he adored her through every one of his senses: visual, audible, tactile, taste, and olfactory. The perfume of spices she used to please him made him wild with desire.” But which spices go into this perfume? Where does Edna apply it? What does it actually smell like? We’re not told. The story is once more being relayed to us second-hand, through summations and abstractions and the filter of opinion. We know that Methuselah likes the perfume, but that’s all we know. The thing itself has not been described. The upshot of all this abstraction is vagueness, not precision.

Enoch Primordial does contain some brighter spots. In the novel’s final third, the episodic narrative finally gives way to something far more engaging: a heavenly trial litigated by some big names that I’ll refrain from revealing, intercut with scenes of earthly carnage as the forces of evil launch a long-gestated assault upon the world of men. While the warfare below struck me as tepid and predictable (and nonsensical — a horde of Nephilim is able to “piece together” twenty-five thousand improvisatory cloth-and-skin parachutes, each five times the size of a giant, all in the space of a few hours, in the middle of a desert, after a forced march, with no apparent source of materials), the heavenly trial constitutes a significant change of pace and a real effort to engage the reader intellectually as well as emotionally. It posits a scenario in which Satan brings a lawsuit against God for the violation of His own law.

Unfortunately, what might’ve been a deliciously disturbing challenge to the reader’s theological complacency is marred by narrator bias. Satan’s well-constructed and potentially persuasive appeals are treated with disdain by POV onlookers. Of course, his is a futile cause from the outset, seeing as he’s presenting oral arguments before the very throne of his Almighty Creator, but futility’s never functioned as much of a deterrent to the Evil One. I expect Satan to put up a bit more of a fight when confronted with First Cause arguments from moral order à la Mere Christianity. The trial could’ve been so much more intellectually terrifying had the Father of Lies actually managed to plant seeds of doubt in the minds of his hearers. Alas, they’re all too perfectly steadfast for that. Oh, and all those on-the-nose references to socialism, feminism, abortion, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama? Yeah, those come off as cheap, forced, and dated. So there’s that, too.

Enoch Primordial dumps a lot of cool ingredients into its antediluvian cauldron. It’s not every story that can accommodate gods, angels, giants, dinosaurs, chimeras, werewolves, vampires, and sorcerers without feeling ridiculously bloated. But, unfortunately, no amount of stirring imbues the sum of those parts with a cohesion or savor greater than that of non-biogenetic soup.

Reviewer’s postscript: Fortunately, no series stands or falls based on the merits of a single title. I am very pleased to announce that ‘David Ascendant,’ the latest installment in Brian Godawa’s ‘Chronicles of the Nephilim’ saga, received a much-more-favorable review on SpecFaith.

I recommend Christians to sit down and read the book of Enoch. Reading it helps to show why we consider some books canonical and some not. Like one thing a lot of books on Nephilim seem to skate over is that they are described as being 3000 ells (roughly 4500 feet!) tall. Another thing is that God refuses the petition of the Watchers by Enoch, which really doesn’t jell with how He tends to accept people who repent in both old and new testaments.

If you are a gamer, surprisingly there is a game that also deals with the Book of Enoch and the Nephilim. It’s called El Shaddai: Ascent of the Metatron, and it’s good, if trippy. On PS3 and Xbox 360.

I’d still like to read Brian’s book in spite of the review. The romance thing is interesting; usually there’s literally no concept of anything but the most chaste romantic love in any Christian books, and “I kissed dating goodbye” still informs too much of our thinking. I think it’s better that Christian writers try to tackle subjects and make mistakes than not.

Oh, the subject of sexuality gets tackled, alright. If you know what I mean. *tee hee!* And, boy howdy, has the pendulum swung!

More on that front with my forthcoming David Ascendant review.