Mixed Messages and Thin Themes

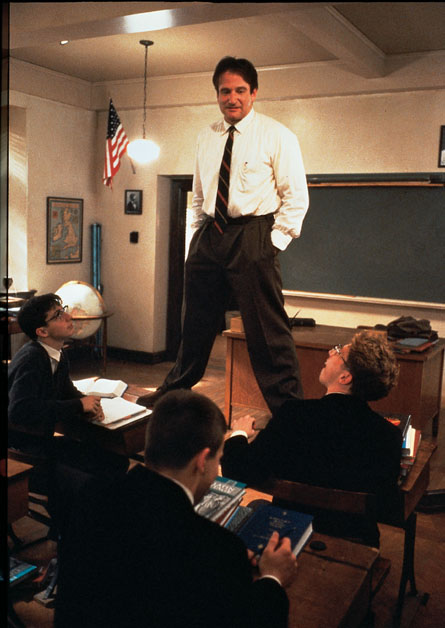

A couple of weeks ago, something reminded me (I don’t recall what) of the movie Dead Poets Society. I could not stop thinking about the movie, and finally checked it out from the library. It had been years since I watched it, long before I started writing. Now, as a writer, I found even more meaning in the story.

Also, I suppose, being older, having kids, and many other life experiences have all combined and changed the things that stood out to me in that movie. One small scene in particular popped out this time. Keating had his students do an exercise to teach them about the dangers of conformity. The headmaster, Mr. Nolan, saw the exercise and asked Keating about it—or more correctly, reprimanded him.

Also, I suppose, being older, having kids, and many other life experiences have all combined and changed the things that stood out to me in that movie. One small scene in particular popped out this time. Keating had his students do an exercise to teach them about the dangers of conformity. The headmaster, Mr. Nolan, saw the exercise and asked Keating about it—or more correctly, reprimanded him.

Keating responds by saying, “I always thought the purpose of education was to learn to think for yourself.”

Nolan says, “At these boys’ age? Not on your life. Tradition, John. Discipline.”

As the movie watchers, we are expected to scoff at that. I’m sure I did when watching years ago. We’re on Keating’s side, right? The whole movie is about nonconformity, after all, not just the one exercise he asks of his class.

Isn’t it?

I found it interesting that very close to this scene is a clip where a rowing crew cruises by. Something I can’t write off as unintentional. Sculling is a sport that requires complete conformity. Every crew member moves exactly the same—must move exactly the same. What would happen if one of the members decided to row at a different rhythm? There are times where conformity is the only way.

The message of the movie is centered around not conforming. And here I say the contradictory message of necessary conformity is sent simultaneously. How can that be?

Simple. Both are true.

(On a side note–Is agreeing that we should not conform in its own way a form of conformity?)

Anyway, my point actually has nothing to do with conformity. My point is that two opposing ideas can be, and are quite often, true simultaneously.

Fiction is the perfect place to illustrate that, as I’ve shown you in the example from Dead Poets Society. Not every story contains a single message, and many times the messages within a story can contradict each other—or at least seem to.

Another example that comes to mind is Jurassic Park, in which the main message is clearly that scientists shouldn’t muck around in what they don’t understand. That playing God, or at least Mother Nature, isn’t meant for us. Bring back dinosaurs when you don’t know enough about them, they will eat you ;). But it’s also shown that the only way to truly learn about dinosaurs is to bring them back. Science, to be utilized fully, cannot be based on conjecture—it must be based on experience.

I recently took a writing class on Fluency in Story led by CathiLyn Dyck that focused a lot on theme, which is broad-spectrum compared to message. In the above examples, I pointed out multiple messages in each movie. However, those messages fall under a broader theme.

In Dead Poets Society, that theme is not specific to conformity or non-conformity, but, I believe, has to do with the idea that trouble brews when one tries to completely stamp out the other. In Jurassic Park, the message is nearly stated outright when Dr. Ian Malcolm says, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” The theme is broader, more along the lines that the “could” and “should” are both necessary.

In Dead Poets Society, that theme is not specific to conformity or non-conformity, but, I believe, has to do with the idea that trouble brews when one tries to completely stamp out the other. In Jurassic Park, the message is nearly stated outright when Dr. Ian Malcolm says, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” The theme is broader, more along the lines that the “could” and “should” are both necessary.

Stories like these make us think. They don’t just present a single, linear message. They allow bits of opposing ideas to struggle on-screen, or on-page, and make us grapple with our beliefs.

Christian fiction often, however, seems to miss the boat on this. Theme is something that runs through an entire novel, something that all the elements point to. Think of it as the roof of the story structure. But messages are support beams. If theme is replaced by a single message, you get a one-dimensional structure. Many Christian novels contain only message, mistakenly included as theme, and the result is that the story feels preachy.

Don’t get me wrong. I see nothing wrong with Christian books having messages, even strong ones. The problem is when a book wraps the entire story around that single message. Everything in the story points in one direction, and the reader finds themselves being told what to think.

The overriding messages in Dead Poets Society and Jurassic Park, and many other stories, come through plenty strong, but they never feel preachy because they are presented under the umbrella of theme. There is no wall blocking the story from all other options.

The importance of non-conformity is clear in Dead Poets Society without making all the conformists look like Nazis. We may think certain characters, like the Headmaster and Neil Perry’s overbearing father, take things too far, but they’re not presented as beasts. Both characters, at their hearts, have the best interest of the boys as their motivations. In Jurassic Park, scientific advancement is not portrayed as evil incarnate, nor is John Hammond—he is a loving grandfather who wants to build an amusement park, after all. And the dinosaurs, well, they just want to survive.

Christians shouldn’t be afraid of stories that hint at other ways of thinking. If the main message has merit (and we know it does) and it is presented properly, it will be seen clearly among the other opposing and/or complementary ideas.

Winter by Keven Newsome is a good example of this. It is the story of a Goth girl who is chosen by God to be a prophetess. His message is clear: God chooses the unexpected to do His work. But it falls under an over-arching theme: We can’t judge based on appearance. There is reference to the theme everywhere. Not just in how Winter is judged by other students and teachers because of her Goth appearance, but also how she judges them. Outward appearance vs. heart is something that shows up over and over.

Winter by Keven Newsome is a good example of this. It is the story of a Goth girl who is chosen by God to be a prophetess. His message is clear: God chooses the unexpected to do His work. But it falls under an over-arching theme: We can’t judge based on appearance. There is reference to the theme everywhere. Not just in how Winter is judged by other students and teachers because of her Goth appearance, but also how she judges them. Outward appearance vs. heart is something that shows up over and over.

But even though theme runs throughout, Keven doesn’t preach his message with every move. Other, more “expected” characters are also used for God’s plan—Winter isn’t always in the spotlight. And Keven uses the story to point out that not every unexpected person gets to do big things. As one character says, “We’re all freaks. It’s just a matter of perspective.” Winter is chosen as a prophetess because of and despite the fact that she’s a “freak.” But the opposing idea that being a freak doesn’t guarantee you’ll get chosen is also there.

Admittedly, none of this would have occurred to me years ago, the first time I saw Dead Poets Society. And maybe you don’t at all agree about my assessment of the messages and themes of the stories I mentioned. They are, after all, my own personal observations, but please take them in context.

What have you noticed about theme and message? Do you see them as different? Do you find a message easier to swallow when it’s not presented as the sole driving force behind a story? Or is one message enough to support a story?

Kat, I believe Scripture affirms that “two opposing ideas can be, and are quite often, true simultaneously.” Like Christ being both fully Man and fully God, like God existing both within Time and outside time, and like destiny being both fixed and fluid. However, this is also, I believe, where Christian fiction stumbles. When / If we place too strict of a doctrinal grid over our stories, we expect BOTH ideas to be neatly framed and explained, and disappointed if they don’t. Which is why Christian fiction so often demands clean resolutions and little ambiguity. We simply cannot tolerate too much paradox.

P.S,, don’t feel obligated to respond to this. 😉

Hah–I gonna reply just ’cause ya told me not to :P.

You say “we”–and yet I wonder, knowing you, Mike, if you’re really including yourself in that term?

And why, as Christians, should we not be able to handle paradox? God Himself is a paradox.

This reminds me of something David Gerrold said when he spoke at a sf/f/h convention I attended a couple years ago. He said that Christians shouldn’t write sci-fi because it goes against sci-fi’s nature, which is to question. He said Christianity claims to give all the answers and therefore Christian thinking is to not question, as though that’s the antithesis of faith.

But I see it the other way–Christianity is about there being *more* than what is seen, and atheism is about saying this is all there is. Therefore, Christian fiction should be less packaged, and should make us think beyond, make us see that there is no way our little human minds can wrap around the complexity that is God and the universe He created.

I remember hearing an excellent explanation of why questioning is not the opposite of faith: A small child is always asking ‘why?’, because they believe that the grown-ups know the answers. So it is with us: we are the children; God is the grown-up.

Love that explanation, Kirsty!

That’s insightful. I wish I understood the difference between message and theme better myself.

For a story containing multiple complicated themes and messages, I highly recommend “Tears of the Cat” by Jarkko Pylvas from Issue 12 of The Cross and the Cosmos. I reviewed a pre-release version yesterday. Everyone will get to read the story sometime around July 1st. I think you should all keep an eye out for it.

Here’s a link to my review, posted on the Anomaly:

http://wherethemapends.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=spacebar&action=display&thread=2230

Hmmm. I must admit, I don’t consider this often, but one trait that annoys me immensely in writing classes is absolute rules. My theory of writing is

“There are three rules to writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

“A writer needs three things, experience, observation, and imagination, any two of which, at times any one of which, can supply the lack of the others”

William Faulkne

Of course, that’s about the craft itself, not the stories, but I think it still holds true.

Paul, it’s been a foggy concept for me, too. But the class I just took really helped clear it up some. I also find it WAY easier to figure this stuff out in someone else’s work :).

Galadriel, thanks for sharing the quote!

Kat,

Thanks for the mention, m’dear.

What’s interesting is how many atheist sci-fi works invoke mystery and a feel of transcendence, in spite of their worldview. I remember being awed by Asimov’s worldbuilding and the sheer scope of his universe. It seems to be a mark of humanity that we can’t escape the more-than-what’s-seen, no matter how much we say we’d like to.

Paul,

I wouldn’t worry. You have an instinct for theme that’s better than any technical description.

Interestingly, a recent WD article on common mistakes cited overdone theme as a recurrent no-no. It’s one area where I think it’s better to just write than to think about it a lot. Perhaps being too intentional about it is what gives rise to the problem Kat points out with message getting in the way.

Galadriel,

Absolute rules are something I can’t stand in writing classes either. 🙂

~Cat

Good post, even if lots of it goes over my head! But then, isn’t that kind of the point of theme? It gets to you without you knowing it. And I guess that’s the trouble with fiction that makes its messages too obvious. In doing so, it robs its own theme of most of its subconscious power.

Cat, I believe Bainespal is different to Paul Baines. Confused the heck out of me at first, too! But when Bainespal posted a review of Paul on the Anomaly, I became fairly certain they’re not the same person.

Eep–I got them mixed up, too! How odd.

And Grace, I like that! Subconscious power. Yes, theme has that. Message is much more direct.

Oh! Like Kat, I just assumed. Yes, I can hardly see Paul reviewing himself. 🙂

Thanks for using Winter as an example! Honestly, and you know this about me already, I write with theme and message as my focus where some people focus on character or plot first. I know it’s a little gray, but honestly that’s my philosophy.

You’re welcome, Keven! And while you may always have your theme in mind while writing, your story is pretty plot-driven–which is good, because then the theme doesn’t override the story.

Thanks so much for your provocative and in-depth thoughts, Kat. I hope we can host your work on Speculative Faith again. Only when we keep evaluating such topics as these from the perspective of readers first (not as writers first!), will we be able to move toward spreading the love of God-glorifying speculative stories.

One can make logical or rightfully pragmatic arguments against this (as Mike and others have done). Yet I feel the best method of opposing shallow themes like that is to appeal to Scripture itself. Does the Bible have a single message? In one way, it does — the Hero, God, defeats the villains / saves the victims, us, in a fantastic story-world. Yet is that a “simple” theme? Not at all. It informs and inspires and spins off so many other truths and beauties and wonders. The Story contains other subplots and themes.

The book of Ecclesiastes alone proves that within the context of the Epic Story of Scripture — as any good story by a Christian author would be — creators are free, and even encouraged by God, to “flesh out” other beliefs and show consequences.

Moreover, not everything is neatly tied up, not because God sets an example of not guaranteeing the victory, but because He has. It is not because God is uncertain in His Story, but because He is certain, that His people have freedom to express some uncertainty and take risks, both in their real lives and in their storytelling.

Thanks, Stephen, for letting me guest post! And agreed–the Bible is a great example of complexity. It is unified, but it is anything but one-dimensional.

Also agreed that analyzing things from the reader’s perspective is so important.

Love this statement, btw: “It is not because God is uncertain in His Story, but because He is certain, that His people have freedom to express some uncertainty and take risks, both in their real lives and in their storytelling.”

See, I’m not so sure we’re using “theme” in the way it’s commonly used. What you’ve given about the Bible, Stephen, is really it’s premise, I think. But I also think the Bible does have a central message that grows out of that main story line, something like The sovereign, transcendent Creator-King is also the redeemer and friend of those who trust in Him. This is the idea that pervades Scripture, I think.

That’s what a theme does. It’s not one of many ideas running through a story without cohesion. Yet, I agree that there may be secondary themes, just as there are in Scripture. But they don’t contradict or detract from that one main point.

Fiction, of course, being written by fallible humans, may have contradictory themes, though I don’t believe those would be particularly strong stories.

The idea that theme and message are different seems to me to be similar to saying children and kids are different: it has more to do with context than it does with meaning.

Becky

Kat, thanks so much for putting into words something that I’ve had on my heart and am working into my storytelling. The world is multi-faceted. There are many things out there, and only because we have the Bible as “Truth” to give us a plumb line and the help of the Spirit of God to reveal it to us can we sort through it all.

So I love the idea of presenting a more realistic story, one where several opposing ideas collide without one trouncing all the others with such finality that there’s no room for people to make their own decisions. I say, let the Holy Spirit lead them. Show it like it is: sometimes the wicked prosper. Sometimes the good guy fails. Sometimes the righteous fall down. Sometimes the bad guy does the right thing. Sometimes nobody is sure who won the battle, because everybody lost a loved one and everyone has wounds when all is said and done. But then you just take your pen and highlight a few things here and there in the story’s flow, just a little, just a hint — just enough that the Spirit can flip the switch and they can see for themselves that maybe the Way is the best way…

Anyway, I love this. And thanks for the tip on the Winter story. I’m going to check it out!

Thanks so much, Teddi. The term multi-faceted is perfect for what I’m talking about :). And yes, it’s that gentle guiding that is a result of letting theme form the story rather than a one-sided message.

I appreciate the comments!

Great post. I’m going to have to wrestle a bit with the difference between message and theme. But I love the part about the opposite propositions being true in the same the story.

Another biblical thing like that: God’s sovereignty/man’s responsibility.

Very good example, Sally. Yes, there are plenty of biblical examples. It was actually somewhat of an epiphany for me not long ago to realize that the Bible is full of things that seem to contradict each other, but do not because both are true. God is not linear.

By presenting two opposing sides of equal merit the reader, or viewer is challenged to think, and draw their own conclusions. I think that sometimes authors of Christian fiction are timid when it comes to this. What if the reader thinks about it, and then draws the wrong conclusions. Therefore, the author feels it’s their duty to say what those conclusions should be. In other words, preach.

But honestly, is someone’s belief system even their own if they are told what to think. Does this really even work? It wasn’t Christ’s approach. He presented scenarios to contemplate: “If any one of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone at her.” “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.” — talk about two opposing truths, at least in the Pharisee’s mind.

I personally love stories that make me think. They’re the ones that stay with me and challenge me to grow.

Ooh, great examples, Shawna! And Christians aren’t the only ones “timid” about this. Think of all the atheist dogma being spouted in public schools–with demands that Christian worldview not be allowed. Why do atheists do that? They are afraid that if just the facts are presented, kids will choose Christianity. If classes include evolution as a theory and Creation as a theory, kids might have to actually decide for themselves, and atheists don’t want that–but if they truly trusted in their beliefs, then they would have no fear that those beliefs would be seen as inferior. We should be the same way–trust that Christianity will hold up in the face of opposition.

You are exactly right, Kat. You see it in politics, too.

Kat, thanks so much for putting into words something that I’ve had on my heart and am working into my storytelling. The world is multi-faceted. There are many things out there, and only because we have the Bible as “Truth” to give us a plumb line and the help of the Spirit of God to reveal it to us can we sort through it all.