Yes, C. S. Lewis Actually Did Want His Fairy Stories to Teach Christian Truth

C. S. Lewis once called a certain method of creating stories “pure moonshine.” He insisted this mechanical process wasn’t how he created his stories—and strongly implied that other Christians ought not use such a method either.1 But in response to this mechanistic method, some Christian creators err on the side of what they might regard as full creative freedom.

“We get to use our liberated imaginations!” they claim. “So let’s not have any of this stuff about how our stories should teach readers.”

Lewis, however, actually did not favor this approach. And I think sometimes we get wrong his description of how he created his own fairy stories. As a result, we might accidentally believe Lewis believed only in imagination and not also in creating stories to teach Christian truth! But first, we must recall the original quote from Lewis, and the very real truth it reflects even apart from Lewis’s original context.

How not to write a Christian fairy story

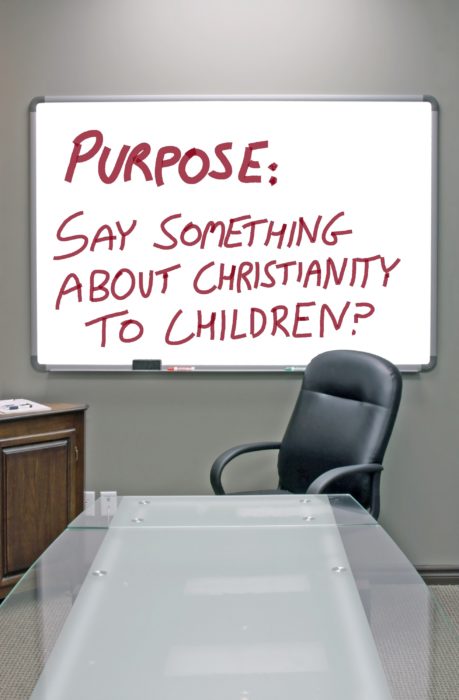

Imagine a board room of frowning and likely monocled elder nonprofit board members, sitting about a table. They are respectable. They are ministerial. On the wall hangs a large wooden cross, right beside the painted-on logo of the nonprofit ministry. Their leader rises to his feet.

“Gentlemen!” he proclaims. “We must find a way to say something about Christianity to children. Now, what shall we do?”

A spiritual hush falls over the room as the men confer in various subgroups. At the meeting’s end, they present their proposals.

“Continued presentation of slow, methodical Sunday-school lessons as before,” says group one.

“More sports celebrities and tastier treats in gatherings for teen-agers,” says group two.

Group three appoints its regent, who shyly raises his hand. “Well,” says he. “I hear that fairy tales might be coming back into vogue …”

Silverware clatters. Heads turn. And the ministerial chieftain pert near loses his monocle.

“Fairy-tales!” he exclaims. “Why—why, Johnson, that’s—that’s brilliant!”

Johnson is taken aback.

The chief minister flushes with excitement, jowls a-twitching. “Why, yes. This is the perfect chance to say something about Christianity to children. We shall use, as our instrument: the fairy tale! Now, what must be done about it? Ah, yes! Of course, we must collect information about child-psychology. We must have a subcommittee. Hire ghost-writers, as we decide what age-group to write for. Then for this tale’s outline, we must draw up a list of basic Christian truths. Ah, yes, and allegory! We must of course fill this tale with ‘allegories’ …”

Lewis: ‘I couldn’t write in that way at all’

Lewis: ‘I couldn’t write in that way at all’

Of course, at the last I’m paraphrasing the very approach that C. S. Lewis specifically disavowed. In his essay, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said,”2 Lewis is making a larger point about a story-creator’s different identities. (More on this in a moment.) To illustrate, he refers to his own creation:

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child-psychology and decided what age-group I’d write for; drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out ‘allegories’ to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way at all. Everything began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t even anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.3

Keep in mind that last sentence’s first two words (“At first …”) as we note Lewis’s real rebuke to this mechanical, ministerial “teaching tools” approach. Even when he limits these phrases to a hypothetical view of his own creative process, it seems clear he views this as “pure moonshine” that is not just about himself. We might wonder what kind of letters Lewis received, or reviews he read, to result in this odd theory about his creative process.

That’s a lesson for Christians who might be tempted to view fairy tales with this kind of pragmatism. It’s not an approach I would ever endorse. If you try it, you might get a not-terrible story. But you won’t get a good or great story—and you won’t even get a very truthful story.

But Lewis doesn’t stop with the raw imagination

But Lewis doesn’t stop with the raw imagination

As I’ve said, however, some Christians repeat Lewis’s quote with a host of assumptions. I haven’t seen any of these very recently, and so I’m not singling out anyone. This is more of a meme I see shared about Christian-creative circles. It might be joined by assumptions like these:

- “Lewis didn’t try to insert Christianity in his books, so neither should we.”

- “We need creative freedom! Making stories is all about imagination, not teaching.”

- “We shouldn’t try to be Christian creators, only creators who happen to be Christians.”

- “If we let down our guard and consider any direct Christian purpose to our stories, we’ll end up becoming (gasp) preachy.”

- “So let’s just focus on creating good things and let anything ‘deeper’ just happen on its own.”

If the pragmatic teach-first-then-fake-“imagine” approach is “pure moonshine,” as Lewis said, then we might call this response a weaker, watered-down moonshine. In fact, it represents another notion that Lewis specifically disavows in his “Sometimes Fairy-Stories” essay.

Three main reasons make this clear:

First, Lewis isn’t writing this essay solely to explain his Narnian behind-the-scenes. He’s exploring a larger theme about the creative process.

Second, Lewis is speaking about how a creator, including himself, starts a healthy creative process—but says the process doesn’t finish there!

Third, Lewis speaks not just of using one’s imagination, but explores the story-creator’s role at three overlapping stages: Author (imagining), Author (giving Form), and Author as Man/citizen/Christian.

Even C. S. Lewis’s phrase for an author’s first imagined images, “the bubbling,” gives form to this concept by describing it with a vivid image (and Lewis keeps building on this helpful metaphor).

Story stage 1: ‘The Author’

Lewis starts his essay by dismissing “the renaissance ideas of ‘pleasing’ and ‘instructing.'” That is, he isn’t interested here in the related question of whether the created work is meant to entertain or to teach. Instead he says:

All I want to use is the distinction between the author as author and the author as man, citizen, or Christian. What this comes to for me is that there are usually two reasons for writing an imaginative work, which may be called Author’s reason and the Man’s. If only one of these is present, then, so far as I am concerned, the book will not be written. If the first is lacking, it can’t; if the second is lacking, it shouldn’t.4

This sets the tone. Lewis is clear that he does want Christian creators to think not just as “the author as author” but also “the author as man, citizen, or Christian.” He’s calling the serious creator to consider not only the imaginative life, that is, the part where you get pictures and start giving them form. Lewis wants us to explore the author’s responsibility as a person. Lewis calls this Man, and loads into the label a biblical definition of a human being who has been redeemed by Christ for a higher purpose.

From here he talks about “the author as author.” This is the fun part.

As an author (or creator), you’re inspired to create something. You get images, usually unbidden, by using your imagination. Lewis speaks of “the bubbling,” what he calls this disorganized array of ideas and pictures. He says this initial creative rush is like the feeling of being in love.

Only then does he give a personal example about his own images: the faun in the wood, a witch on a sleigh.

Yet Lewis does not stop there!

Story stage 2: ‘The Form’

Story stage 2: ‘The Form’

Lewis says of the initial outpouring of images and ideas:

This ferment leads to nothing unless it is accompanied with a longing for a Form: verse or prose, short story, novel, play, or what not. When these two things click you have the Author’s impulse complete.5

Story-making doesn’t end with the images alone; otherwise you would have no story that others could enjoy. The form starts to organize these images and give them purpose. For the first story in Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series, he said the fairy tale was a perfect form for “what’s to be said”:

As these images sorted themselves into events (i.e. became a story) they seemed to demand no love interest and no close psychology. But the Form which excludes these things is the fairy tale. And the moment I thought of that I fell in love with the Form itself: its brevity, its severe restraints on description, its flexible traditionalism, its inflexible hostility to all analysis, digression, reflections, and ‘gas’. . . . The fairy tale seemed the ideal Form for the stuff I had to say.6

Lewis doesn’t explore this here, but this idea of “the form” fits perfectly with God’s original creation of the world.

Genesis 1:2 says “the earth was without form and void.” Then God intervened. Over six days, he gave his new world its form. Finally, on day six, he breathed into a living, physical form that would reflect back his own image, the imago Dei.

Then God calls his created humans to imitate his behavior by stewarding the Earth’s resources (Genesis 1:28). That is, men and women will act as God’s royal regents in God’s world, using God’s stuff to make stuff. They must take a luscious garden, and cultivate soils and plants and spaces. They take raw minerals and polish them into gems (the same kinds of human-shaped gems that later feature in biblical descriptions of heavenly cities). Later, they take true-life stories, and re-sort their elements into imaginary stories.

Such a concept long predates Lewis: the idea of cultivating our world. We take God’s gifts, and we train one another, share knowledge, and reshape these resources. For a story’s author, we don’t leave our images “raw” and hidden to ourselves. Otherwise we would have no story! We polish them, reshape them, turn them into stories proper—stories that can be shared for the benefit of many other people.

This is no sacrifice of creative freedom. It is an embrace of creative freedom. In Lewis’s case, he found his chosen form, the fairy tale, a great liberation for the potential of his images. It is through discipline, organization, and limits that any story finally breathes the breath of life.

Story stage 3: ‘The Man’

Story stage 3: ‘The Man’

Finally we come to the moment that may surprise some Christian creators. Yes, C. S. Lewis does believe in expressing faith through imagination by intention. Yes, he does believe in “saying something about Christianity to children” on purpose. And yes, he does believe that in his creative case, while “at first there wasn’t even anything Christian about [his images], later “that element pushed itself in of its own accord”—and by his willful design as a Christian person!

Remember, Lewis has spoken of two earlier creative stages: the imagining of images, and then the cultivation of these images into a Form. These are the tasks of the “author as author.” Now comes the author’s final identity. Lewis calls this “the Man,” and associates this label with the terms “citizen, or Christian.” The first term represents a Christian creator as member of the community (or city, or country, or humanity altogether). The second term indicates the creator’s position as a new man—a person redeemed for Kingdom mission by Christ.

For Lewis, this identity of human/citizen/Christian is just as essential to making the story:

Then of course the Man in me began to have his turn. I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could. . . .

That was the Man’s motive. But of course he could have done nothing if the Author had not been on the boil first.7

Yes, Virginia, Lewis did want to create stories to “say something about Christianity to children.”

Lewis did eventually want his images, given the fairy tale form, to teach Christian truth.

You can affirm that fact about his stated motives, and yet reject the “Sunday school associations” that stifle our imaginations, or ruin authentic emotional response to the gospel. Lewis didn’t insist on some artificial, inhuman divide between imagination and truth. He stated that his own stories started with images and grew into a form, and then Lewis found these stories’ human/citizen/Christian purpose in helping “all these things,” biblical truth, “appear in their real potency.”

How does Lewis’s creative structure help Christian fans?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

In this podcast episode, Zackary Russell and I suggest some specific lessons this teaches Christian story creators. Yet these truths apply far more broadly to Christian fans of amazing Christian-made stories. Lewis’s creative structure may help us grow beyond some cliches about creativity. He can also help us find, enjoy, and support the stories by Christian authors who don’t get stuck in false imagination/truth divides.

First, we need to grow beyond the impulse to apologize for enjoying stories that have overtly human/citizen/Christian purpose.

Second, we need to expect that Christian creators are not just split-apart imagination-machines, but are also Christian, human citizens.

Third, let’s expect great Christian-made stories to begin as embryonic images. Then we must also expect them to walk as upright “forms,” then mature into “adults” with clear Christian purpose. Neither Lewis nor Jesus Christ expects some false either-or purpose. It’s both/and.

Finally, let’s review and clarify Lewis’s quote near the essay’s beginning:

. . . There are usually two reasons for writing an imaginative work, which may be called Author’s reason and the Man’s [reason]. If only one of these [reasons] is present, then, so far as I am concerned, the book will not be written. If the first [Author’s reason] is lacking, it can’t [be written]; if the second [Man’s reason] is lacking, it shouldn’t [be written].8

God the Author created his people. Jesus Christ the Son of Man saves his people.9 As Christians made in God’s image, we reflect all these identities. Therefore, in all our creative pursuits, we must reflect the Author as Creator and the Savior as Man, practicing our form-cultivated imaginations to share his beautiful truth with one another by design!

- This article is inspired by our recent Fantastical Truth podcast episode 35: Did C. S. Lewis Say It’s ‘Pure Moonshine’ to Create Stories that Teach Christian Truth? ↩

- My copy of this essay comes from a collection called Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories. You can likely find this essay itself printed online, even in full form (of questionable legality). Just search for a distinct phrase, like C. S. Lewis “pure moonshine.” ↩

- C. S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said,” collected in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, edited by Walter Hooper. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- And of course, the Trinity’s third Person, the Holy Spirit, works “behind the scenes” to accomplish God’s purpose. ↩

Thanks for this.

I’ve been a lurker and occasional commentator on Speculative Faith for several years.

I’m so glad you’re in the public square, publishing Spec Faith and Lorehaven and bringing great stories to the world’s attention.

I enjoyed your recent article “Yes, C.S. Lewis Actually Did Want His Fairy Stories to Teach Children”, and your and Zach’s podcast. I completely agree, images and imagination written out with purpose, or rather, expanded and polished purposefully, are the foundations of creating great stories and imaginative fiction.

Because great fantasy and speculative fiction has had such an impact on my life, I’ve recently completed a non-fiction book on magic and meaning in imaginative fiction, from a Christian perspective.

“Fantastic Journey – The Soul of Speculative Fiction and Fantasy Adventure.”

Being a Christian writer is challenging, let alone working to succeed at it. Your encouragement means a lot to me and other authors.

I admire what you and so many authors are doing inside Spec Faith.

Thank you so much!

THREE MONTHS LATER …

Azalea, I’d like to think I was just very occupied at the time, and that is why I didn’t see your highly encouraging comment until just now. Thank you very much!