Wizards, Witches, and The Bible

Speaking of King Manasseh of Judah, the Bible counts him as an evil king because:

Speaking of King Manasseh of Judah, the Bible counts him as an evil king because:

And he caused his children to pass through the fire in the valley of the son of Hinnom: also he observed times, and used enchantments, and used witchcraft, and dealt with a familiar spirit, and with wizards: he wrought much evil in the sight of the LORD, to provoke him to anger.

(2Chron 33:6)

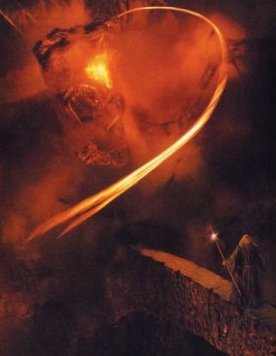

Such verses, there are several, never have a positive thing to say about these common fantasy tropes. It is also why some Christians have a hard time accepting Christian fantasy that uses these same names for the abilities of characters in their novels. So some condemn J. R. Tolkien for using a wizard as one of the primary hero-protagonists in his story, Lord of the Rings, as a “good guy.”

Most people of sane mind get that in a fictional novel the world will not work like ours. Indeed, when is the last time you saw a wizard in a long, pointy hat casting a spell? Much less a spell that worked? My last time may have been while watching a magic show, which everyone knew wasn’t real. Middle-Earth—full of wizards, elves, dwarves, and hobbits among other fine folk—our world is not.

Likewise, often magic in the fictional world doesn’t work by the same rules as it does in ours. It can range from being sourced by God, God’s creation, use of creation, deception (trickery), and accessed through actions, words, thoughts, or will. As is often used in time travel stories, much of our technology and knowledge today would earn us the title of wizard, which literally means one with knowledge or a wise one, if we were transported back even 100 years ago.

Still, some will choke on the use of such titles in a Christian fantasy novel. They might also choke when King Nebeccanezer gives Daniel the title of “master of all magicians.” (Daniel 4:9)

Could it be that such titles are context sensitive? What is the real-world usage and meaning of the Bible’s denunciation of those titles?

Based upon Biblical examples like Moses and Elijah, the issue isn’t about the ability to do seemingly magical miracles. Moses even gets into a contest with Pharaoh’s magicians in order to prove whose god is greater. A contest which Moses handily won. (Exodus 8)

Rather it is the perceived source of the ability where the Bible makes a distinction. When it condemns things like sorcery, enchantments, astrology, and magic, it does so because those doing them don’t acknowledge that these abilities come from God. They are the names used by pagan nations often pointing to their gods as its source, rather than the God of Israel. Such people are like Simon who wanted to buy the power of God so he could own it rather than become a servant of God. (Acts 8:18-19)

Those who acknowledge God as the source of any “magical” abilities and are humbly submitted to Him, using it for His purposes and will, are instead called holy ones, prophets, servants of God.

One group of pagan magicians the Bible does paint a positive picture of, are the wise men who come to see the baby Jesus. All indications are they came from the Babylonian region and were part of the “magicians” of that land. Based on the writings of the “Master of Magicians,” Daniel, they interpreted the unusual star in the night sky to indicate the birth of the Christ. These pagan wise men—that is, wizards—are praised because they recognized who God was and paid homage to Him.

Likewise abilities inherent in God’s creation are not considered evil. Instead how we use them might be.

Having the knowledge to know when to plant a crop and the best conditions for its growth isn’t frowned on in the Bible. Indeed, Jesus uses such examples in his teachings. (Matt 13) We are not considered to have evil powers because we have the knowledge of how to make plants grow.

Nor would we consider the harnessing of radio waves in order to talk to one another over great distances to be evil. Transport cell phones to Biblical times and you would have magic. But it has nothing to do with a power inherent in the person, only the knowledge of how to use the power God created around us.

In most fictional universes, such “amazing” abilities are sourced from one of these three fountains: power inherent in the created world, power inherent in a person or group of people, and power derived from an outside source or person.

For each of those categories, what makes it compatible with Christianity, no matter the term applied to it or the persons involved, is whether it is sourced from God or not. If God created the world or people with those powers, then it is a Christian-compatible form of “magic.” If God is ultimately the source of any wizard’s/enchanter’s abilities, as opposed to demonic or pagan beliefs, there is no contradiction between it and the Bible’s denunciation of such secular and pagan practices.

For a Christian fantasy, my line has always been that the good guys, whether they be called wizards or prophets, are those who use their power in the service of God, knowing it comes from Him, while the bad ones are those who believe it is a power they control apart from God. This fits with the dividing line drawn in the Bible more so than mere titles attached to persons.

What is your dividing line and why do you draw it there?

This is a useful explanation, I think. Too many people see the word “wizard” and immediately assume “evil”. This is a good article to point to the next time I come across that mindset. Thanks, R.L.!

I don’t have a hard-and-fast dividing line, I guess. If the “magic” in the storyworld is actually more of a science, that negates it as magic to me, and a lot of stories are like that. In most cases fantasy magic is an innate ability of the user or a scientific part of their world. I haven’t read many books where it wasn’t, but I’d probably not be comfortable with those books and put them down, unless the good guys were – as you said – clearly using these powers as gifts of God and in His service.

I’ll keep this in mind for my mom sometime. It reminds me of how the Noldar in the Silmarillion were called “Nomin,” (The Wise) by the early Men.

magic is etymologically synonymous to might, thus source matters, not name