Why Materialist Magicians and Sour Stepmothers Are Cruel To ‘Cinderella’

Occasionally at SpecFaith we discuss why Christians condemn fantastical stories, and may forget that secular authorities hold even worse views about fairy tales or science fiction.

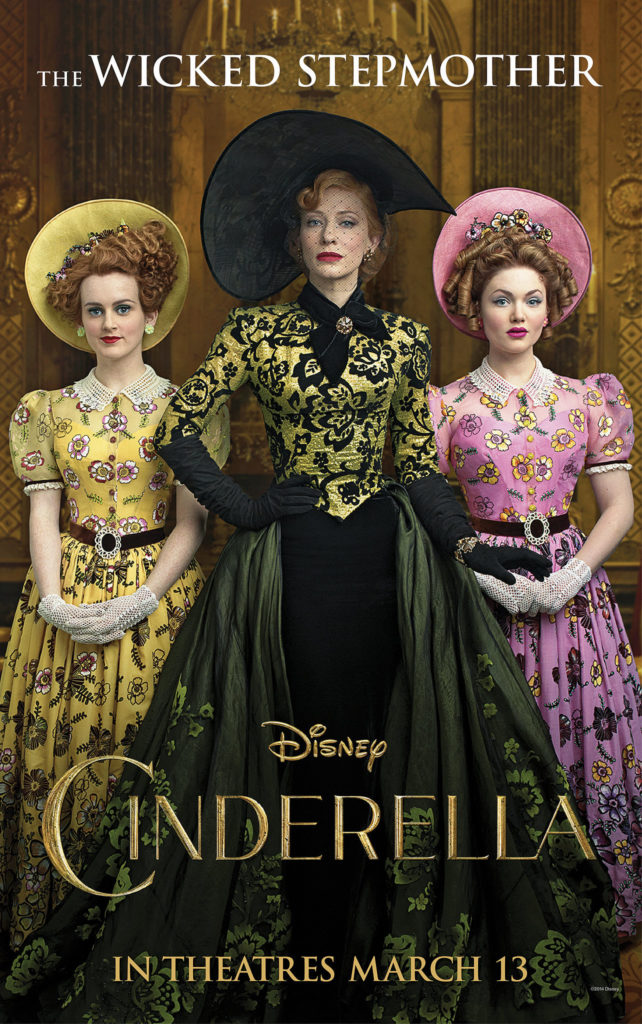

This month’s fantasy controversy is inspired by Cinderella, director Kenneth Branagh’s live-action adaptation of the classic fairy tale (adapted from the original Disney animated film). I loved the film, because thanks to positive reviews I expected a classic, fantastical, and fun yet thoughtful version of the fairy-tale story that respects the source materials.

But that wasn’t good enough for some reviewers and high-falutin’ Child Specialists who expected the film to be something more, something More Important than silly fairy tales.

Where have we heard that before?

One reviewer1 said she wanted Cinderella somehow to marry her childhood princess dreams with secular-feminist empowerment fantasy. She concluded the new Cinderella just doesn’t have a waspishly narrow social-justice waistline as it should. Also in her view the movie is not nearly as amazing and progressive as Frozen.2

Second we hear the “be careful little eyes what you see” response, courtesy of someone who probably never heard the catchy yet arguably moralistic Sunday-school song:

“Depicting a female who appears utterly helpless until a male swoops in and rescues her from all of her troubles sends a troubling message,” [psychotherapist and author Amy Morin] tells Yahoo Parenting. “Girls may learn, ‘I can’t solve my problems, but a boy could.’ It’s much healthier for girls to recognize their own problem-solving skills, rather than look to boys as the solution.” 3

And finally, the “mind of metal and wheels” response, courtesy of this chap:

“It’s a misguided notion that these stories are going to have lasting significance to a child,” David Elkind, a professor and department chairman of the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Development at Tufts University, tells Yahoo Parenting. “Cinderella doesn’t do any harm. It’s just a charming story. Kids enjoy fairy tales and these stories fulfill fantasies.”4

I don’t know these speakers’ motives or personal backgrounds. But I do know that some who condemn fairy stories, or who hold themselves above stories, end up effectively cast in the story. Professing to be very important real-world heroes, they become something else.

Materialist magicians

Three materialist magicians from three different stories come to mind — Uncle Andrew from C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, the formerly white wizard Saruman from The Lord of the Rings, and Lord Voldemort from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Three materialist magicians from three different stories come to mind — Uncle Andrew from C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, the formerly white wizard Saruman from The Lord of the Rings, and Lord Voldemort from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Uncle Andrew is likely Lewis’s personification of a phrase Lewis used in The Screwtape Letters.5 Andrew is not a true magician (whether good or corrupt), but a dabbler and a fool. In the new land of Narnia, with magic blossoming all around him, he only thinks how impossible it is. The man who made magical rings refuses to believe a Lion can sing. And his sense of “wonder” is only aroused when he wrongly concludes he can use Narnia’s magic to get rich.

Saruman is similar but far more sinister and ambitious. A member of the magical Ishtari charged with helping Middle-earth, he becomes ensnared by misdirected pragmatism— use any means necessary to “help” the land. Finally his goal is corrupted. He does not enjoy or help the land, only uses it. As Treebeard says, Saruman “has a mind of metal and wheels and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.”

Saruman is similar but far more sinister and ambitious. A member of the magical Ishtari charged with helping Middle-earth, he becomes ensnared by misdirected pragmatism— use any means necessary to “help” the land. Finally his goal is corrupted. He does not enjoy or help the land, only uses it. As Treebeard says, Saruman “has a mind of metal and wheels and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.”

Lord Voldemort was literally conceived under the effects of a spell that replaces true love with illusory infatuation. The wizard grows to use magic not in the standard, daily-life scenarios normal witches and wizards use it, but for his own selfish and loveless ends.

If you see a film like Cinderella (or only hear about it, as some critical voices seem to have done) you may have two responses. The first is like mine: happiness that a team of creators got it right and made such a splendid spectacle filled with pictures of restored humanity. The second is not like my response but is close enough: you don’t like those kinds of stories but at least recognize what the creators wanted to do for those who do like these stories.

But the response of the materialist magician is like this: “That sort of story is of no practical value. It doesn’t help with my own work. It won’t be Useful to help people be educated, or find jobs, or spend their lives enslaved to my joyless struggle for some kind of Social Justice. And there’s no way this story could inspire my (vaguely defined) view of better humanity.”

The materialist magician dabbles with beauty and truth but refuses to embrace its wonder and its Maker, uses magic as a machine to achieve selfish political ends, and even replaces a vision of restored “normal” humanity with into a life of loveless and naked ambition.

Sour stepmothers

The “materialist magician” motif explains the aloof and patronizing responses to Cinderella and other fantastical stories. That doesn’t yet explain the bitter and hostile responses.

One reason may come from Cinderella itself, at the moment when the film’s supposedly weak and helpless princess confronts her stepmother. Lady Tremaine, having subjected her stepdaughter to verbal and other ill treatment, now brings her abuse to a whole new level. She even shares her tragic backstory, the kind that often gets some villains off the hook, but this story will have none of that: Tragic backstory does not excuse abusive behavior.

One reason may come from Cinderella itself, at the moment when the film’s supposedly weak and helpless princess confronts her stepmother. Lady Tremaine, having subjected her stepdaughter to verbal and other ill treatment, now brings her abuse to a whole new level. She even shares her tragic backstory, the kind that often gets some villains off the hook, but this story will have none of that: Tragic backstory does not excuse abusive behavior.

“Why are you so cruel?” Cinderella asks her, genuinely struggling to understand

“Because you are young, and innocent, and good,” stepmother spits back. “And I …”

Brilliantly for the film, Lady Tremaine leaves it unfinished before locking Cinderella away.

In my interpretation, even the sour stepmother can’t admit the fact: She simply wants to destroy goodness because she herself is not good and can’t stand the reminder.

In this story version, Cinderella has not been merely a suffer-in-silence figure. She is a true heroine who strives for impossible ideals — an attitude of servanthood and love for others, despite their wickedness. Her outlook reflects Christ (who does take human crap on himself but only for so long). And Cinderella’s outlook happens to balances dual biblical truths near-perfectly: that yes, people must turn the other cheek in response to some attacks; but also that we must wisely discern between such surface attacks and worse attacks on our very humanity, when we must defend not merely ourselves but the image-of-God within us.

That balance of suffering-servanthood and human-rights-defense makes no sense to some activists. Their lives, too, are often driven by of metal and wheels and not love of growing things: No, everything must serve The Cause, and The Cause must serve My Rights (under the guise of improving mankind and such). And when someone opposes you — or seems to — why, that’s an attack and you must strike them down or else get hurt or abused again!

Is this why some reviewers can’t stand Cinderella and make their opposition so personal?

Is this why some recoil from the story’s picture of a more-biblical response to injustice?

If so, then we definitely need more fairy tales like Cinderella. We also need a certain other Story that is even more beautiful, bursting with color and good conquering evil, and that refuses to go away or serve our lesser goals of materialist-magic or sour-stepmothering.

- Jaclyn Friedman, Why Disney’s New Cinderella Is the Anti-Frozen, Time, March 15, 2015. ↩

- E.g., that over-praised film that doesn’t earn its surprise villain reveal, doesn’t do much else that’s new, and in which the self-centered “Let It Go” song that everyone loves and praises is actually subverted by the story’s own predictable yet biblical picture of self-sacrifice. ↩

- New ‘Cinderella’ Film Sparks Backlash, Jennifer O’Neil at Yahoo.com, March 17, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Senior demon Screwtape muses, “I have great hopes that we shall learn in due time how to emotionalize and mythologize their science to such an extent that what is, in effect, a belief in us (though not under that name) will creep in while the human mind remains closed to belief in the Enemy. … If once we can produce our perfect work—the Materialist Magician, the man, not using, but veritably worshipping, what he vaguely calls ‘Forces’ while denying the existence of spirits—then the end of our war will be in sight.” ↩

Fairy tales often have inescapable creepy subtext. No matter how you try to spin it, Beauty and the Beast reads like glorification of Stockholm Syndrome. I still like it because I think it has great things to say about the power of kindness and lurrrrve, but that doesn’t make the situation of “Imma isolate you till you love me” any less super-duper creepy at all. Nothing can really be done to make Sleeping Beauty any less functionally identical to a shiny rock. How’s that for existential nihilism, if your existence can be easily replaced with a shiny rock?

We’re kinda stuck with it, but that doesn’t mean we have to accept it uncritically. Trying to make the good justify the existence of the creepy is pretty creepy itself.

Perhaps the original fairy tale can be creepy — you did not also mention the recently infamous stepsisters cutting off toes to fit their feet into the glass slipper, etc. — but that doesn’t explain or excuse this most recent mind-of-metal-and-wheels criticism of the recent film version of Cinderella.

I haven’t seen the recent movie, but the recurring complaint about traditional fairy tale princesses like Cinderella is that they’re hella passive characters. Most of them don’t do shizz; they wait around until fate drops a prince in their laps (which is a really backhanded way of motivating people to be good, isn’t it), or at least does all the work to pave a red-carpeted road to one. And the prince-dropping-process is apparently the only interesting thing to happen to them, since we hear fudge-all about anything else in their lives. They’re hella static characters, too. They don’t change, they don’t learn lessons, they don’t grow.

Maybe Brannagh brought some of that in: at least he made an effort for the romantic pairing to develop some chemistry, from what I’ve seen of the trailers (“You can’t marry a man you just met,” amiright?). But when you really get down to it, Cinderella is about the universe deciding that the nice, pretty girl should be rewarded with an upper-class hottie. That’s worth questioning.

Perhaps the most important line in the film was Cinderella’s “I forgive you,” to her wicked stepmother.

In “Pride and Prejudice” the problems of two of the main characters are also solved by marrying wealthy men. (Of course that story has certain moral advantages over “Cinderella” mainly being about learning to be self aware than about simply improving your situation.) I would never wish to encourage people to think that getting married will solve all their problems (it is more likely to create them) and I would never wish to return to a society where women couldn’t earn their own money. But there may have been times when that really was the only option for some people.

Also, for whatever it is worth, I, a boy, could be and am a pretty passive person. It isn’t necessarily the best character trait in some situations but passive people exist and it doesn’t seem fair to me that they should never have characters to whom they can relate.