What Does it Mean for a Story to be “Christian”?

Back early in 2017 I wrote a post for my personal blog that attempted to define what a makes a story Christian or not Christian. I made a chart and numbered categories that wound up being awkward and not necessarily helpful in terms of format. Yet I think I was on to something–something that’s worth simplifying and repeating here.

Note that Johne Cook, a Christian writer friend of mine years ago said something on the topic of Christian stories that I objected to at the time. I think what Johne said didn’t originate with him, but he’s the first person I heard ask the question, “Does a Christian bricklayer lay Christian bricks?” He applied that question specifically to the idea whether or not a story can be considered Christian.

The question of course points out that only a person can actually be Christian or not Christian–that no physical object has the power to believe or not believe, to have a religious life or not have a religious life. In this analogy a story is likened to what makes it up, the pixels on a screen, the printed ink on the pages of a novel, the sum total of all the letters, numbers, and punctuation marks in a tale. My objection at the time was that, “No, this isn’t fair. Stories are built out of ideas and ideas can very much either be Christian or not be Christian.”

For me, at the time, it seemed a very simple question to which I offered a clear and simple response. Yet Johne’s point has grown on me somewhat over the years. While it is true that the the words and letters in a story combine to constitute ideas, those ideas don’t occur in a vacuum. The reader brings to the story her or his preconceived notions and steers them in a highly personal way. Sometimes a reader is inspired to believe something that’s the complete opposite of what a writer intends in a story. A story about doubt may inspire belief while a tale full of references to faith can stir up religious skepticism.

One can make the point that since only the writer can be Christian (or not), Christian writers should follow the inspiration they receive and attempt to craft the best stories possible in terms of being entertaining and thought-provoking, without worrying whether or not their content is Christian. I actually see a point to this, to writers of personal faith following where inspiration leads them, focusing on the quality of the storytelling and letting whatever religious elements enter the tale to do so naturally (in fact, these are the kinds of speculative fiction stories from Christian authors I sought to collect in the Mythic Orbits 2016 and Mythic Orbits Vol. 2 anthologies I’ve published).

Yet from the reader’s point of view, I find this unsatisfying. We can in fact identify what kinds of ideas are the “bricks” of a story and say in a general sort of way if the story is Christian–that is, if a story’s ideas line up with notions in harmony with Christian thought. We can also say in general if the ideas that line up with Christian thought are portrayed in a positive or a negative light. It’s perhaps clearer to reference stories that are hostile to Christianity as a means to define a type of tale than it is to identify we might think of as “friendly,” so I’ll give examples of both.

I broke up stories into a number of different categories I considered Christian, which I’m going to list below (abandoning the numbering system and chart I created before that was more confusing than helpful). With each positive example, I will also list a negative example:

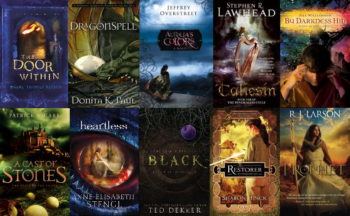

Top Ten Christian Fantasy Books according to theartistlibrarian.blogspot.com

- Christianity or Christian ideas overtly referenced in the story and the reference is central to the tale (as in without the religious reference, the story would disappear). Tosca Lee’s Demon, a Memoir would fall into this category. Scriptural demons are referenced and are the subject of the story in a way that reinforces what the Bible says about demons. The Da Vinci Code would be a negative example of this type–Christian ideas are central to the story, but the story goes out of its way to refute or marginalize those ideas.

- Christianity of Christian ideas are overtly referenced in the story but the references are not central to the story (as in, you could edit out the references to faith and still have a story left–which doesn’t necessarily make the references unimportant). Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s The Mote in God’s Eye or A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle qualify. A negative example, in which Christianity is overtly referenced but could be edited out (changed to a form of non-religious statism perhaps) would be Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale. Note that Handmaid’s Tale gives a great example of what I mean by the ideas of a story not occurring in a vacuum. I may see in the story an attack on all of Christianity based on the implication that all Christianity is inherently oppressive to women and naturally would lead to the type of dictatorship seen in the story–yet others might only see an attack on a false version of Christianity and find nothing to be concerned about with Handmaid’s Tale. (Note also someone might reasonably disagree with me on how central to the story the Christian references are in Handmaid’s Tale).

Polar Bears: Baddies in Narnia, Good guys in The Golden Compass. Image source: Patheos.com

- Christianity or Christian ideas are referenced in a story indirectly, but are clear, in a way central to the tale. The first and most important example of this would be The Chronicles of Narnia books by C.S. Lewis. A negative example stems from Phillip Pullman’s The Golden Compass.

- Christianity/Christian ideas are referenced indirectly, but are clear, in a way not central to the story. This probably happens more often than I think, but I find this to be a bit of a rare bird among the stories I read. Richard New’s short story “Escapee” has an indirect but-easy-to-deduce reference to Christianity that is not central to his plot (this story was published in Mythic Orbits 2016). Frank Herbert’s Dune novels make reference to religious institutions that are not Christian-but-are-like-Christian that could probably be removed from the story and which mostly reference those institutions negatively. Though Hebert also referenced Christian ideas of a messiah-figure in ways that are central to his story and they reveal that sometimes it’s difficult to say if a reference is positive or negative–but Hebert definitely was not interested in promoting traditional Christian ideas of the Messiah.

- Christianity/Christian ideas are referenced in a way that’s debatable, in a way central to the story. By “debatable” I mean that no effort is required to remove any Christian content when a book gets made into a movie (as L’Engle’s Wrinkle in Time had all its Christianity edited out). When made into a movie, the content is simply ignored or re-interpreted in a way other than Christian. I would say The Lord of the Rings is an example of this. Christian notions of good and evil and how the ring represents evil, the example of Frodo as a sort of suffering Messiah, Aragorn as a returning-Christ figure, Gandalf as a resurrected-Christ figure, are all central to the story, yet are routinely ignored by most people who view the screen version of Tolkien’s work. The best negative example I could come up for this is Robert Heinlein’s Revolt in 2100, in which a fundamentalist government takes over the United States (and is defeated by the “good guys” in the tale). What makes this debatable is Heinlein created a new, futuristic religion that runs his dictatorship that isn’t directly related to Christianity–so his shot at the Christian faith isn’t as overt as Margaret Atwood’s. Yet maybe this novel would be better listed with my #3 type of story above–while it’s possible to create a tale that criticizes Christianity in a way so indirect as to be debatable, most people writing anti-Christian allegories aren’t too subtle.

The religious cult leader in Conan the Barbarian–a shot at Christians? Eh, maybe…maybe not…Image source: Tumblr.com

- Christianity/Christian ideas are referenced in a way that’s debatable, in a way not central to the story. We could argue Tolkien’s The Hobbit contains Christian symbolism, though I’m not quite sure what that would be. Clearly story does not hinge around such symbolism. Negative examples might be found in Dune or other science fiction that portray quasi-similar to Christian figures not central to the story in a negative light. Perhaps though the James Earl Jones religious leader in the original Conan the Barbarian movie might qualify as a peripheral covert negative reference to Christian leadership. Maybe. 🙂

- Moral Message. A story without any clear references to Christianity, whether overt or allegorical. Even if someone tries to insert Christian references, they don’t quite fit. Yet the story shows a world of conflict between recognizable good and evil, in which we cheer for the good and fear the evil. The original Star Wars (i.e. Star Wars, A New Hope) was like this. The way to subvert a moral message is to have a story that promotes something as good in the tale that actually isn’t moral. Without giving a specific example, I think Christians would in general object to stories that promote a sexually immoral lifestyle as a good thing.

- Amoral Message. Sometimes a story is just a story and even when you look at it from all angles, not much in terms of moral content can be found. An event or series of events happen without any real discernible commentary on good or evil, right or wrong. When I made my original chart for this, I listed Kat Heckenbach’s short story “Clay’s Fire” as an example of this (from Mythic Orbits 2016). Yet as I discuss this topic, I find it’s rather hard to enjoy a story in which there is no morality at all. Sure, “Clay’s Fire” and a number of other stories that focus on events, in particular on survival, can be interesting without an sense of right or wrong appearing in the tale. But most stories have some form of morality, right? A truly moral-neutral story is a rarity. Though it’s true that a negative version of an amoral message would be to present characters in which everyone is totally a shade of gray to such a degree that the story questions if good and evil aren’t merely matters of opinion and are not in fact based on this people do.

- Immoral Message. The story flips the standards of right and wrong as Christians understand them. Killing enemies is good and enjoyable (as in Heinlein’s Starship Troopers) because our species needs to propagate. Or taking pride in oneself is good (Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged) even if at the expense of others. Satan is a good guy, angels are boring, witches are cool, Christians are sinister (all of us), etc, etc. Not too many Christians write this kind of tale. Though I suppose we could as a satire.

So anyway, I’ve shown it’s possible to look at the ideas in a story and pass it through some kind of a matrix. Note that it’s also possible to pass a story through a search for dirty words and sex scenes and have it come up clean but in other ways be anti-Christian. For example, I’ve only read part of the Da Vinci Code, but I don’t remember it cussing or being racy. Yet it clearly is intended to imply Christianity is false (a product of an ancient conspiracy) and always has been.

Which of course means on the other side a story could have foul language and suggestive themes but still have ideas that support Christianity. That’s not me suggesting I want to read stories with foul language (I don’t because I don’t want to say those words in my mind as I read) or that I want to read erotic scenes (I don’t because that will cause me to visualize the scene in a way not good for me), but that the question of what does it mean for a story to be “Christian” is more complex than a simple check for things people often find offensive. And it’s more complex than the categories I made.

Yet I hope my list of categories helps readers think about the kind of work worth their time to read–and the kind of stories authors want to craft. Gray, morally neutral stories do exist, but in fact, most stories are morality tales in one sense or the other. So as we lay our “Christian bricks” into stories, we should be aware of our moral content. Yes, we should follow what interests as readers and what inspires us as writers–yet we really should think about stories in terms of “Is this good? Is this right?”

What are your thoughts on story types? On what it means for a story to be Christian? Please share in the comments below:

A very good list, thank you, especially for weirdos like me who write Christian for a secular market, if that makes any sense.

I think, in general, when people talk about Christian works of art, they mean art made by Christians FOR Christians. It’s funny, because many Christian artists view their work as being evangelical in nature, but art is one of the worst ways to evangelize. Part of that is because the impact of the actual Gospel on a person’s life is so unbelievable that it strains credulity when put into fiction. It’s just not convincing. But eating dinner with someone who says, “Look, this changed my life. See me? It’s obvious, isn’t it?” is much different. In that way, I see many artists live under a delusion and make their stuff with an intent their art is poorly structured to achieve. Whereas the actual marketplace purchases their stuff for a completely different reason (“uplifting entertainment,” etc.).

A novel is not a sermon. It can cause cravings for holiness–like Lewis’s account of how the fantasy novel Phantastes led to his disillusion with atheism by making him love what was good.

If you read the novel Anna Karenina it actually is pro family and pro Christianity. A cautionary tale about letting warped eros take over. The movies mess it up. Tolstoy would have been horrified. (He was a prude.)

I highly recommend On Moral Fiction by John Gardner. A late life convert to Christianity. An English professor who chain smoked and rode motorcycles.

As far as “Christian novels” go C.S. Lewis had some fun comparing the notion to Christian cookbooks.

Ironic because he made a solid template for a type of Christian book…

To answer the question in a totally utilitarian way, a story is Christian when it is accepted by the Christian subculture. Of course, taking it that way, that would imply that Thomas Kinkade is Christian art even if it’s not religious art.

But is that even wrong, tho?

I think that’s good enough. . . the title itself (Christian art) is nothing but utilitarian, imo.

Christianity is so pervasive in our culture that people probably sometimes reference it because it feels natural (some people might feel like they are referencing old literature or something without feeling like they are actually referencing Christianity. Bits of the Bible have become common sayings, for instance) So they might be trying to sound cool, or make their story interesting, without knowing that they are writing a story in a way that could be interpreted as insulting/attacking. Though some people definitely do attack on purpose.

Whether or not a story is Christian fiction partly has to do with authorial intent. What is the story trying to say or reinforce? Does the author want to consider it Christian fiction? Sometimes, when plotting out a story, I feel tempted to call it Christian fiction even if the chars aren’t believers and don’t think about God much. But, that’s because it is part of a story world that has God in it and thus fits into an overall narrative. Or, maybe, there are other books in the series/story world that are more overtly Christian. Still, though, it can be hard to know what to do with those books, since plenty of other people reading them wouldn’t call them Christian.

Some people really hate it when a story/author is Christian, especially when people talk about it. I spoke to someone that love the Dragonkeeper Chronicles, but felt very annoyed to see so many discussions involving the book related to Christianity.

To reference something that probably just makes Christian references because it’s ‘cool’, let’s consider Death Note. There’s a few references in the first opening alone:

There are a few other Biblical references in the series itself. The main character, Light, (AKA Kira) also eventually says that he will become the god of the world, etc. It’s interesting since they are have Christian imagery, but still use Japanese ideas. In a lot of ways it subverts Christianity, since the only deity type things we see in the show are Shinigami(which are basically the Japanese version of grim reapers), and a lot of anime shows people becoming yokai, gods, etc as a result of actions they take during their lives, so when Light talks about becoming a god of sorts, it sounds (slightly) less far fetched and crazy than it would in a Western tale. In the end, the parallels are there and not always great, but it doesn’t feel like an actual attack on Christianity, just part of the story.

On the other hand, I haven’t read much of this comic series and find this particular one funny, but it’s far more likely that it was meant in a mocking way:

https://www.webtoons.com/en/comedy/adventures-of-god/ep-2-where-fossils-came-from/viewer?title_no=853&episode_no=2

My first book was never intended to be “Christian”. Yet, after years of struggling to write, then submitting my life to Christ, that’s exactly what it became. When I say it’s “Christian”, it’s primarily to warn would-be readers that the story contains a strong religious theme. It is overt–a depiction of the Christian struggle set in a fantasy world overrun with vampires–of coming to Christ and learning to trust Him. I’ve had Christians and non-Christians alike read the story. So far, I’ve only received one “bad” review (I say “bad” because it was two stars for being overly religious–otherwise, they enjoyed the story–so, in my mind, it’s not actually a bad review). Again, I attempt to clearly state that my story is Christian in an effort to spare those who might choose not to read an overly religious story. That said, I wrote the story I felt called to write for whoever God chooses to share it with. Can my story save the lost? No. Might it offer encouragement to struggling Christians and a clean read in a sea of filth? Yes. Can God us it to share Biblical truth and provide a stepping stone toward Him? I know that He can. I pray that He will.

Thank you for sharing that!