The Psychological Study Of Creativity – Or, You Experience What You Read

Stories matter. Any reader can tell you this. We cry because a beloved old yeller dog, which never actually existed, dies. We laugh at the pig’s tail applied to the imaginary greedy Dudley Dursley. We cheer when the fictitious Aslan returns alive.

Clearly stories affect us in powerful ways. We skip meals and stay awake late at night. We “forget to breathe” and find our muscles coiled tight until our heroine is out of danger, at least for now.

Such physical effects indicate that all this pretend is very real. But how can this be?

At long last, scientists are beginning to take note and study the power of fiction. One of those leading the way is Keith Oatley, professor emeritus in the Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology at the University of Toronto. He and his colleagues devised a way to measure the effects of literature on the human psyche. In summary

the central assumption Oatley developed to frame their research [is this]: “When people are reading literary fiction, they’re creating in their mind a simulation of experience. It’s a simulation that’s cognitive as well as emotional….” (“Toronto scientists determine that fiction can change personalities” By Natalie Samson, accessed August 12, 2011 – emphasis mine)

In essence, it seems, these scientists are saying we readers have our own little holodecks in our minds, and consequently we mentally experience the stories we read. And that changes us.

At least that’s the hypothesis.

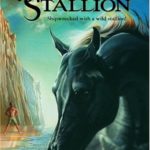

I get that. Growing up, I was a huge fan of the Walter Farley books (The Black Stallion, The Black Stallion Returns, The Black Stallion and Satan, The Black Stallion’s Filly, and many more, my favorite being The Black Stallion Mystery). Somewhere during that reading phase, I decided I wanted a horse. I knew I’d bond with a horse and that I could ride like the wind.

At that point, however, I’d done nothing with horses except ride an old nag at summer camp where we walked our mounts behind a guide for an hour.

I never did own a horse, but my confidence around them did not wane, despite my own lack of experience. You see, I didn’t feel inexperienced.

Years later when I visited a friend who did own a horse and we went riding, the particular mount I was on tried a clever trick to unseat me. My friend was somewhat amazed that I didn’t end up sprawled in the dirt.

Some time later I did a “rent-a-horse” ride in Colorado. After several return visits, the guide let me take my horse out on my own. Again I had the experience of a horse trying to deposit me on the ground, this one by rearing.

No problem. After all, I’d experienced much worse from the Black. Oh, wait. No, that wasn’t actually me. That was a character in a book. But it felt like me.

It felt as if those experiences had become part of my acquired knowledge. Not in a conscious way, to be sure, but as I look back, I find it easy to believe that I wasn’t fearful and didn’t overreact in the real life circumstances because of the simulated experiences of my childhood.

How many other experiences have I lived through behind the eyes of the characters in books I’ve loved? And how have those changed me?

Oatley, whose scholarly work Such Stuff As Dreams: The psychology of fiction (Wiley-Blackwell) is now available in North America, and his fellow scientists developed experiments to “examine what Oatley calls the ‘big five personality traits’ – extroversion, emotional stability, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness” (ibid).

I don’t know about those particulars, but here’s what Oatley’s publisher says:

Oatley richly illustrates how fiction represents, at its core, a model that readers construct in collaboration with the writer. This waking dream enables us to see ourselves, others, and the everyday world more clearly.

Yes, fiction matters, with readers and writers collaborating. And the end result is clearer vision.

Always? Or can fiction lead us to believe something about ourselves and the everyday world that is not true? Now that’s something else to explore.

Becky, this is a bit scary, actually. Already I was considering more after your recent writings that good Christian fiction should help us merely find truth, but is rather based on truth that we already know and works from there. Thus I was thinking about a new way to describe how fiction helps a Christian “simulate” truth in what-if scenarios — and based on the world simulation, the only comparison I was coming up with was the holodeck.

When people can say they learned how to save a life, or survive in the wilderness — or in your case, ride a horse better! — through reading fiction, we begin to see that it’s both more powerful than we give it credit for. It is also more realistic, which also gives the lie or even insult to the common line that “fiction is only entertainment.”

I enjoyed the article. I had often asked myself why I cared about people that didn’t really exist…

Here is proof that reading is better qualification that staying at a Holiday Inn Express the night before! 😉

This is why it’s so important for beginning writers to understand how important it is to maintain “the suspension of disbelief” in their readers.

In Waking the Dead, John Eldredge does a fabulous job of explaining why we are so passionate about fiction when he elaborates on the definition of “myth” as “a story that brings you a glimpse of the eternal” and ” any story that awakens your heart to the deep truths of life.” He goes on to make examples of Braveheart, The Lord of the Rings, The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, The Wizard of Oz, even The Matrix to draw connections between these and the human search for truth and our place in our life-story.

Later, he goes on to write: “There are stories you’ve loved; there are characters you’ve resonated deeply with down deep inside, maybe even dreamed you could be. Do you know why? Deep is calling unto deep. They spoke to you–they speak even now–because they contain some hint or glimpse into your true self.”

Yeah, I’d say that defines fiction as pretty important to the human experience. 😀

Seriously, the book is a wonderful tool for anyone needing growth in their walk with God, but also edifying for writers who also happen to be Christians. It helped me realize that what I do is important after all, and not just “entertainment” or contributing to “escapism.”

Great comments. I hadn’t thought of how clearly this refutes the “just entertainment” crowd. But I wonder how readers could ever hold that view. I mean, haven’t we all been changed at some level by what we’ve read? I know I’ve had my eyes opened to a lot of new places and experiences — from a peasant Chinese woman to a social scientist/adventurer sailing across the ocean in a boat made out of papyrus. From a Polish alchemist to a white wolf, from a Jewish freedom fighter to a selfish Civil War era Southern belle — I’ve “gone” places and “lived” in times that have expanded my horizons.

Is that not a common experience for readers?

Most definitely reading is entertaining, but only? Not by a long shot.

Becky

Very interesting stuff. And that last question bears thinking about. I hope you’ll post on it again. My quick answer would be that fiction can, indeed, lead us astray.

I think of characters in books acting upon impressionable minds the way living friends to. There is a kind of peer pressure, I think. It’s not like your character friends will dump you or get mad at you if you don’t go along with their crazy schemes, but if you think they are cool, you want to be like them.

Intriguing article, Becky! As a lifelong reader, I take the impact of story for granted, but it’s interesting to see a study that actually backs it up. I’ve experienced fiction educating on a factual level–places, eras, and events that I’ve learned so much about by “living” through–and I’ve also experienced the emotional impact of story as I’ve traveled with characters on journeys that spoke to my own life circumstances.

But just as it is possible for fiction to shape our thoughts and beliefs in positive ways, I think it can also have the opposite effect, because we respond emotionally to stories and what they portray. It’s something to consider as a writer, and also when exercising discernment as a reader.

Oh, by the way, I also loved the Black Stallion books when I was young. 🙂

Great stuff! Who says literary characters aren’t “real”? They impact the real world just as if they were real persons, real friends and loved ones.

It sounds like these scientists are exploring something similar to what James K. A. Smith calls “ritual desires.” A ritual is essentially a miniature story that shapes the loves and desires of the heart, and so he thinks recovering a solid worship liturgy is the only way Christians will be able to “form the heart” of the worshiper and counter the “liturgies of culture,” consumerism and materialism and all the rest.

Janet Yolen, in her book Touch Magic writes “The child reading the fairy tale takes it—and the writer (for the story is the writer)—into his heart. There is literary Eucharist: heart to heart, body to body, blood to blood. The writer is parent to all children who read what he or she writes” (25).

Combining this with what you wrote, it sounds like we experience fiction indeed, as a bonding like unto Holy Communion to author and to story.

Interesting post. I know from experience there is definite validity to this argument. I too loved Farley’s Black Stallion and read the books many times until I eventually felt like an expert. Then there was a time in my life that was very stressful and I had lost a lot of self-consciousness. I settled into the Wheel of Time series and, with its strong female characters, I found myself growing in confidence, standing up for myself when I needed to. I find it all quite fascinating.

Sally, I was thinking that question I ended on might need a post of its own, but I deleted the to be continued part of the final sentence. I thought instead I’d see if any visitors had any thing particular to say on the subject first.

Becky

As to your last question, I have no empirical evidence, but strongly suspect that, for example, reading romantic fiction and/or watching romances on TV or in the movies can lead to unrealistic expectations of how a spouse should act or perform, and, probably, occasionally even be the primary cause of a divorce.

Thanks for the post.

P. S. “What made the change in Lewis? In a word, fantasy. It is no stretch to say that Lewis’s faith journey began as a result of reading stories that were dripping with Christian truth — awakening within him a desire for something he didn’t possess.” Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware, _Finding God in the Land of Narnia_ (Tyndale House: 2005) The quotation is from p. xi. The stories referred to are those of George MacDonald.

We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness.

–On Faery Stories

A very good point. Stories are powerful.

I’ve been wondering for some time whether there is a difference in how we experience stories between reading words and viewing pictures.

If we read words we have to help create the image inside our heads. It’s a more participatory and deeper experience. Just seeing images is shallower and doesn’t involve us as much. Yet may people today communicate by copying speak from movies. So that’s a more communal experience, where reading is more private. Yet the private experience of reading the same books is often shared with others, as the comments show.

My childhood was based on reading, still pictures and radio. I find it hard to imagine how the mind of a person works when it grew up with such a volume of moving images as we have seen lately. Are we the same kind of people? Is it the same kind of experience. I need to check out the book mentioned to see if it has anything about the experience of watching fiction.

[…] Ken Rolph: I’ve been wondering for some time whether there is a difference in how we… 4:07 am, August 18, 2011 […]

[…] fiction is, as I quoted last time from the publisher’s blurb, a model for life which readers create in collaboration with […]

[…] as we saw last year (see “The Psychological Study Of Creativity – Or, You Experience What You Read”), recent studies of the brain have shown that reading fiction does far more than what scholars once […]

The concept of a “waking dream” that a writer and reader construct together as a novel is read is fascinating. One of my favorite sci-fi/fantasy authors, Lois McMaster Bujold has referenced this phenomenon before. She makes the point that our fiction (as writers) is not our own. It will be experienced in ways we never expected or intended because of what our readers each bring to the table as they read it.

What if we, as Christian authors partnering with the Holy Spirit of the Creator, wrote novels specifically with that collaboration in mind? What if we refrained from spelling everything out and allowed the reader to see the ‘scarlet thread of truth’ woven through the story only if the Spirit showed it to them?

When Jesus told parables, He said it was because He only wanted those who had “ears to hear” to understand them. He told the story and allowed the Holy Spirit to ignite understanding in the hearts of the hearers.

I’d like to write stories like that. Something that burns bright and engages people and draws them close enough that if the Spirit desires it, a spark jumps across the breath between them and the pages and ignites their souls with hunger for God, or passion for the helpless, or hope for a better future. Yeah… that’s how I wanna write.

[…] in a bunch of spiritual gobbledygook. Beyond the realm of Christendom, as we discussed here at Spec Faith some years ago, psychologists have done brain-imaging studies and have written books and articles […]