The Place Of Hope In Speculative Fiction

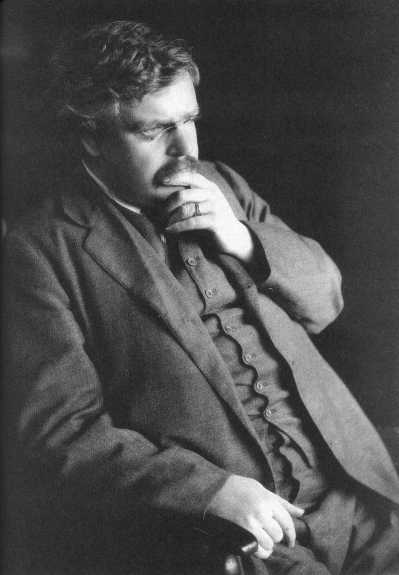

Modern literature takes insanity as its centre. Therefore, it loses the interest even of insanity. A lunatic is not startling to himself, because he is quite serious; that is what makes him a lunatic. A man who thinks he is a piece of glass is to himself as dull as a piece of glass. A man who thinks he is a chicken is to himself as common as a chicken. It is only sanity that can see even a wild poetry in insanity. Therefore, these wise old tales made the hero ordinary and the tale extraordinary. But you have made the hero extraordinary and the tale ordinary — so ordinary — oh, so very ordinary. (from Tremendous Trifles)

Only in fairy tales did hope ascend.

For the devils, alas, we have always believed in. The hopeful element in the universe has in modern times continually been denied and reasserted; but the hopeless element has never for a moment been denied…. The greatest of purely modern poets summed up the really modern attitude in that fine Agnostic line—

“There may be Heaven; there must be Hell.”

The gloomy view of the universe has been a continuous tradition; and the new types of spiritual investigation or conjecture all begin by being gloomy. A little while ago men believed in no spirits. Now they are beginning rather slowly to believe in rather slow spirits. (from Tremendous Trifles)

I find Chesterton’s perception of “modern fiction” — stories written in a realistic style nearly a hundred years ago — eerily similar to stories written in a realistic style today. When the imagination is separated from spiritual reality, it seems to stall on the bleak and the horrible.

It fits with what we know. Life is … not as exciting as we wish. And the consequences of our actions and choices are more dire than we expected. Then waiting at the end is … the end.

How different for the person who sees spiritual realities as more real than physical realities. The here and now is the prelude, not the main act, and most definitely not the final act.

What happens here is better because with it comes Promise. And Hope.

The one point I disagree with Chesterton on when it comes to story is his view of the protagonist of a fairy tale:

As I see it, a Biblical worldview says the soul is “sick and screaming” but that the world has also gone mad, though at times it may appear dull.Realism means that the world is dull and full of routine, but that the soul is sick and screaming. The problem of the fairy tale is — what will a healthy man do with a fantastic world? The problem of the modern novel is — what will a madman do with a dull world? In the fairy tales the cosmos goes mad; but the hero does not go mad. In the modern novels the hero is mad before the book begins, and suffers from the harsh steadiness and cruel sanity of the cosmos. (from Tremendous Trifles)

So the problem a fantasy deals with is — what does a soul sick and screaming do in a world gone mad? Certainly painting it in those terms, such a story does not appear to traffic in hope.

But I suggest the solution to the problem offers the truest hope — such a soul can do noting to right the world. He must trust in someone greater than himself.

The idea that the soul is healthy, I think, is perhaps the cruelest of concepts, one that leaves the reader, knowing himself to be less than whole, wanting.

As I see it, then, there are two kinds of stories that lead to hopelessness — ones that are realistic about the physical world but not the spiritual, and ones that falsely infuse hope in a healthy soul.

How do you see it?

There is a fascinating chapter in Chesterton’s ORTHODOXY called “The Ethics of Elfland” where he talks more about this.

Sherwood, thanks for the heads up. I happen to have Orthodoxy checked out of the library and immediately jumped over to that chapter.

Becky

Yes, I definately see that. Even in my favorite TV show “Doctor Who,” you really get the sense that the main charactter needs an answer to the world, but nothing will give it to him.

Galadriel, that’s how I see so much fiction. Either there is something temporary to which the characters cling for hope or there is bleakness and a sense that all a person can do is make things a little better for now. It’s not hope in the universal sense of the word.

Thanks for your comment.

Becky

Chesterston may prefer a hero who is a type of Christ. Not as perfect as Christ, of course; but one who, when plopped into the center of a universe gone mad, begins to bring order to it, tries to make sense of it, and by his journey, arrives at or creates peace. A better ideal would possibly be the first Adam, who was flawed and sinned, yet was at heart a fundamentally decent guy who desired to please God. Or Noah–

I don’t believe that every story has to begin with a crazed protagonist plopped into the middle of a world gone mad, and then going nuts searching for the meaning in it. I’ve read stories like that. I hate them. I especially hate the existentialist modern versions that insist on making the statement that “there is no meaning to the universe.” How horrid!

Actually; to be scrupulously fair: I’ve only read two like that. Vanity Fair, and another much more recently published novel that was so horrible, I promptly forgot the name. It was billed on the fly-leaf as something along the lines of a “strangely endearing story fraught with hope. Mostly, it was fraught with totally incomprehensible dreck. ICK.

I decided I didn’t care who reads junk like that; I wouldn’t be any more. When I realize I’m holding a book like that in my hands, I reshelve it and move on.

Krystie, I’ll admit I hadn’t thought of a type of Christ and how that character would fit into the two models Chesterton offered. But I’ll admit, I’m wary of a character that seems so “good” or so capable that he himself doesn’t need saving or that he can save himself. That story seems more humanistic than it does Christian. Adam is an example — a fallen person very much in need of rescue and incapable of providing it himself no matter how decent he may have appeared.

Now Noah presents an interesting contrast — considered by God righteous and rescued accordingly. He seems like an anomaly, as does Enoch who was so close to God, He took him to heaven, apparently bypassing death.

More common, it seems to me, was deceiver Jacob and fearful Gideon, self-willed Samson and “least among us” David.

By the way, something I didn’t address is that the soul “sick and screaming” doesn’t generally present as a “crazed protagonist.” The sick and screaming part is properly masked from the rest of the sick and screaming souls, some of whom have already been rescued. Consequently, part of the story is for the character to confront his own vacuous soul and to do what it takes to change his condition.

Therein lies real hope, I believe, not in the temporary fix of a set of circumstances. In some way, I suppose you can think of it as a conversion story, but it doesn’t have to be “just” a conversion story. There’s a whole lot of story that can be written about what rescued living might look like.

And perhaps Chesterton was thinking of that kind of story.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Krysti.

Becky

I suppose you’re right, if you’re telling a redemption story. It works fine in the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. But stopping there misses the rest of Chesterson’s thought, which was thus:

He’s talking about the hero having basic morals. Sure, we know the hero is a sinner, but we want to root for a Good Guy, and we expect the hero in a fantasy story to be a Good Guy. Or at least be some kind of anti-hero, where he’s dark and broody, but still does the right thing in the end.

Talking about sharing Hope, well, if we’re in the shoes of a Good Hero who has to confront evil and monsters, and overcomes them by sticking to his moral code, doesn’t that convey the hope that Good will win in the end? Very often in our corrupt world, Good doesn’t seem to ultimately triumph. That’s why we need stories with happy endings. To convey the hope and comfort that there is Justice and Good beyond this world, and someday everything will be put right.

Sure, we know the hero is a sinner. He won’t always follow his moral code. He’ll break it sometimes. But that’s what keeps us reading. We all fall in the mud, and we want to see the Hero get up and keep going, with the aid of Grace or magic or however else the story is set up.

Starting with a sick and screaming hero and introducing a sick and screaming world–well, you wind up with Thomas Covenant.

Kessie, it’s so interesting that you mentioned Thomas Covenant because I always thought Stephen Donaldson got it right except for the end. He showed the mess we are and the mess we make, but he had no solution, no redemption, no answer.

I suppose in some ways, I do think every story should be a redemption story, though I thought Krysti made a good point about creating a character who is a type of Christ. Gandalf didn’t need to be rescued because he himself was the rescuer, even when he went down to apparent defeat. Aragorn didn’t need rescuing either.

But I guess what I’m challenging is the notion that apart from grace — magic, perhaps — a character can be morally good enough, or in the case of an anti-hero, overcome his own natural bent to act in a moral way at the critical moment, to triumph over evil. To me those stories don’t seem Christian. They seem humanistic. Because the truth is, Man apart from Christ has no hope and will not conquer evil.

Now the part that you mentioned from Chesterton that may make all the difference is this: “it is assumed that the young man setting out on his travels will have all substantial truths in him” (emphasis mine). I think such an assumption could be made in Chesterton’s day, but in ours? I think most in our culture would think the substantial truths originated within the man himself, not from the God who made him and saved him. That’s why I think we need to write different stories than simply the hero conquering evil.

Becky

I know what you’re talking about, and I’ve seen those stories where the main character is just “good enough”.

But even Gandalf and Aragorn felt the temptation of the Ring. They resisted it, though, and that’s the difference between them and say, Denethor. Denethor succumbed to the lust for power and knowledge and eventually despair, making him an interesting and dangerous antagonist.

I think when we’re working with characters who are “good enough”, like the little boy in the Back of the North Wind, or the heroes in the Dragonlance books, we’re assuming that they’ve already had their redemption experience. They’ve been changed somewhere along the line, and now they’re aligned with the Good gods, or the North Wind herself. The heroes I keep thinking of, who have “goodness” in themselves, usually have some external force of Good for whom they are working.

It’s the characters who strive to be good in an ultimately meaningless world that are so heartbreaking. Like in The Positronic Man by Asimov. Andrew has the Three Laws to make him Good, sure, but at the end, the most human thing he can do is die. (And even then Asimov can’t quite abandon all hope of a Hereafter.) They leave you closing the book and going, “Wow, that was sad and hopeless.”

[…] Kessie: So the problem a fantasy deals with is — what does a soul sick and screaming do… 6:40 pm, September 5, 2011 […]

Yes, Kessie, I think perhaps Christian fantasy could have a character readers might assume is redeemed, that whatever goodness he displays is a result of a change that’s taken place as part of the backstory. I guess I’d hope, though, that would be shown.

I know I’m reacting to our current cultural trend that places Man in God’s stead. The spiritualism of the day looks within where a person is to find inner strength and goodness and whatever it takes to overcome.

My natural question, then, is whether or not our Christian stories look different. I think they should.

Since I fault this current cultural spiritualism with a wrong view of Man’s nature, I suppose I want to come out on the opposite end and say, Man by nature is a sinner, not good. Sure we were made good, but we have this little insurmountable problem that requires a miracle-working God.

Yet I realize we aren’t all called to write the same story. How boring that would be. But I think it’s important to keep our worldview in focus as we write. Who, after all, is Man? Where does courage and kindness and moral excellence come from?

Otherwise, I think we writers can easily be swept up by the spirit of the age, and once again we’ll find Christians mimicking the world rather than leading the way.

Becky