‘The Hobbit’ Story Group 9: Barrels Out Of Bond

If you happen to have any empty wine barrel lying about, pry off its lid, squeeze inside, and ask a handy hobbit to seal the lid on after you. Take a good look around. What do you see? I must admit, your sight is more faithful to this Tolkien chapter than Peter Jackson will be in the forthcoming The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (releasing Friday, Dec. 13 in the U.S.).

Some fans wouldn’t give any filmmaker a pass for adaptation deviation. I certainly don’t, when the adaptation is as severely bad as that of the third (but not last?) Narnia film, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010). But here I want to be wise about what stories work best in different forms of storytelling. That’s why I give Narnia’s second film Prince Caspian (2008) a pass when most criticize it: The book would always be difficult to film. Even the much-beloved BBC adaptation relegated Caspian to a short-film setup for the third story.

So consider chapter 9 of The Hobbit. Much of it focuses around characters whom you cannot see. First Bilbo is invisible, scampering about the Elven palace for days. Then, still sneaking about, the brave little hobbit (whom we all admire) packs the Dwarves inside Elven wine barrels — where, again, you can’t see them. Then Bilbo grabs onto a barrel and rides it out the palace’s secret entrance, still invisible and accompanied only by invisible Dwarves.

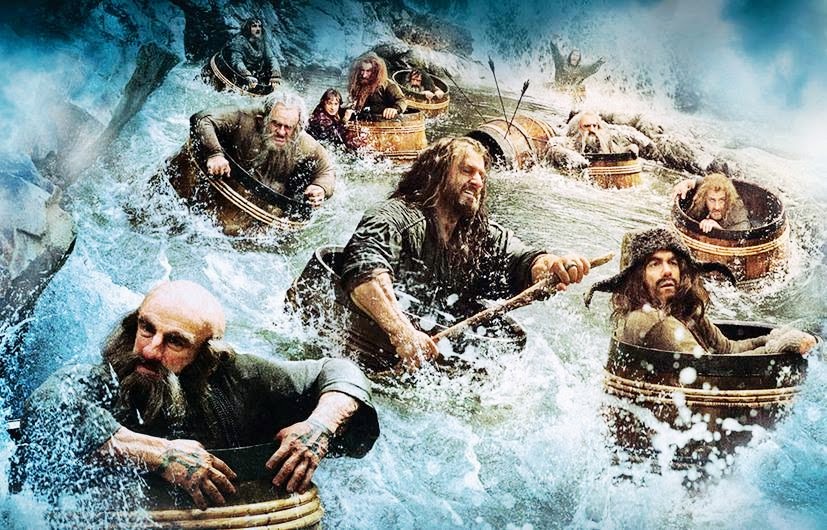

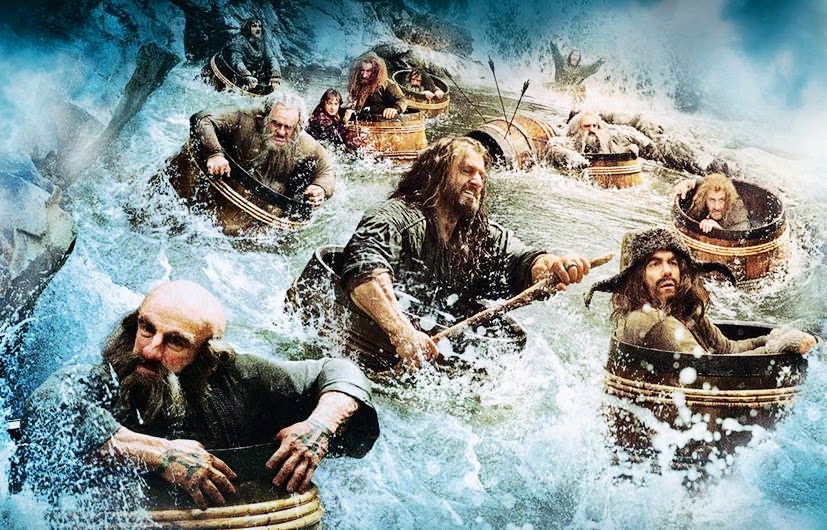

That’s why we’re seeing publicity photos of the Dwarves actually broken out of the barrel-tops to look around. Invisible folks just don’t translate well to film. We’ll need to see them.

Of course, none of that explains why Jackson has evidently inserted even more fight scenes.

Also, you just know Bilbo won’t be alone in his all (or mostly?) invisible quest to help the Dwarves. Surely he’ll have help from the added Wood-Elf Legolas (a fair addition, as his father appears in The Hobbit and Tolkien likely hadn’t thought of his son yet) and the new-for-the-film-only shooting-up-heroine Elf Tauriel (no woman I know is at all a fan of this).

Ergo, expect plenty of revisions at this part of the film. Hope this advance warning helps you paradoxically enjoy the film even more — and enjoy exploring this chapter of the book.

Chapter 9: Barrels Out of Bond

- Read chapter 9 in its entirety.

- Here the Dwarves are captured by the same Elves who are described as “good people” in the previous chapter. How can “good people” function almost like bad guys? Can two groups of people have a legitimate disagreement, but neither side be evil? How may this be different from views of heroes and villains? And why then are goblins clearly bad?

- If you were Bilbo, trapped in an overall good yet inescapable Elven palace, invisible but with a need to eat and stay out of others’ ways, how would you handle the situation?

- For the second time in the story, it’s up to Bilbo alone to rescue all the Dwarves. Does this seem redundant? Even if it does, does that make you want to stop reading the story? (If you don’t, then even a technical story redundancy is not a real problem, is it?)

- The Wood-elves, and especially their king, were very fond of wine. … Very soon [after drinking] the chief guard nodded his head, then he laid it on the table and feel fast asleep. (pages 165, 167) Is this a lucky coincidence? Or does it seem to say anything against the Wood-elves, or them enjoying wine, or even them drinking too much? In general, what are the views of classic fantasy authors about wine and drinking and getting drowsy?

- … Bilbo, before they went on, stole in and kindheartedly put the keys back on [the sleeping elf guard’s] belt. “That will save him some of the trouble he is in for. … He wasn’t a bad fellow …” (page 168) What does this tell us about Bilbo and his reaction to the Elves?

- It was just as this moment that Bilbo suddenly discovered the weak point in his plan. Most likely you saw it some time ago … (page 170) Did you? … And have been laughing at him (pages 170-171). Were you? … But I don’t suppose you would have done half as well yourselves in his place. (page 171) What do you think you could have done to escape? Is this one of those “why not just explain the whole thing to the good captors” incidents?

- Again we find Bilbo in a miserable situation. Can you think of a similar adventure? What made all that misery worthwhile later? Perhaps the joy of laughing about it to others?

- … Now we are drawing near the end of the eastward journey and coming to the last and greatest adventure, so we must hurry on. (page 175) Have you noticed the plot structure changing — from road-trip quest, to escape story, and now another type? What do you think about The Hobbit thus far, and (for new readers) where may the story go next?

The dwarves aren’t good people though. It’s Thorin’s pride that causes him to be imprisoned, because he refuses to tell why they are in the elf-king’s domain. In fact, Dwarf pride and greed are the forces behind everything that happens. The barrels are the last attempt to hammer home to Thorin that he shouldn’t have pride at all; Gandalf knew that without Bilbo they’d die horribly, and Thorin should have taken the hint then.

This is why it’s a little dangerous for the movie to keep trying to make the dwarves cool or alter the parts of the book where their pride or greed does them in. The book is establishing that Thorin is not a nice person, and his reactions aren’t due to byronic heroism, for when he winds up trying to become Smaug at the end of the book, replacing one dragon with a dwarf army. Buttering him up endangers this.

Oh, I’m certain that Thorin will quickly become an even more conflicted character. Dwarves can be cool in general, but Thorin’s greed is fortunately being shown as a staple of his motives and journey. It’s starkly revealed in the part 2 trailers.

Perhaps not, but I disagree with Tolkien’s assertion that the Wood-elves were genuinely “good people.” Tolkien evidently didn’t have the cynicism that I carry, which is mingled with my Christian beliefs about sin and depravity. And I’m guessing that Tolkien would have called the dwarves “good people” too, despite their greed. Thorin’s greed is a mortal flaw, but the mythologies that Tolkien drew from were filled with mortally flawed heroes.

Thorin was more in the wrong in this specific case than the Wood-elves were, but the elves have a long history of greed and pride, too. So, it’s pretty clear that Tolkien’s use of the term “good people” does not mean “sinless people” or even “basically well-intentioned people.” I guess it more-or-less means “flawed people who are fundamentally on the side of good.”

True, the invisible and dark scenes of that chapter would be difficult to film.