The Esther Syndrome

The story of Esther is often considered one of the Bible’s greatest love stories, which is too bad. Love – romantic love, anyway – doesn’t have a whole lot to do with it.

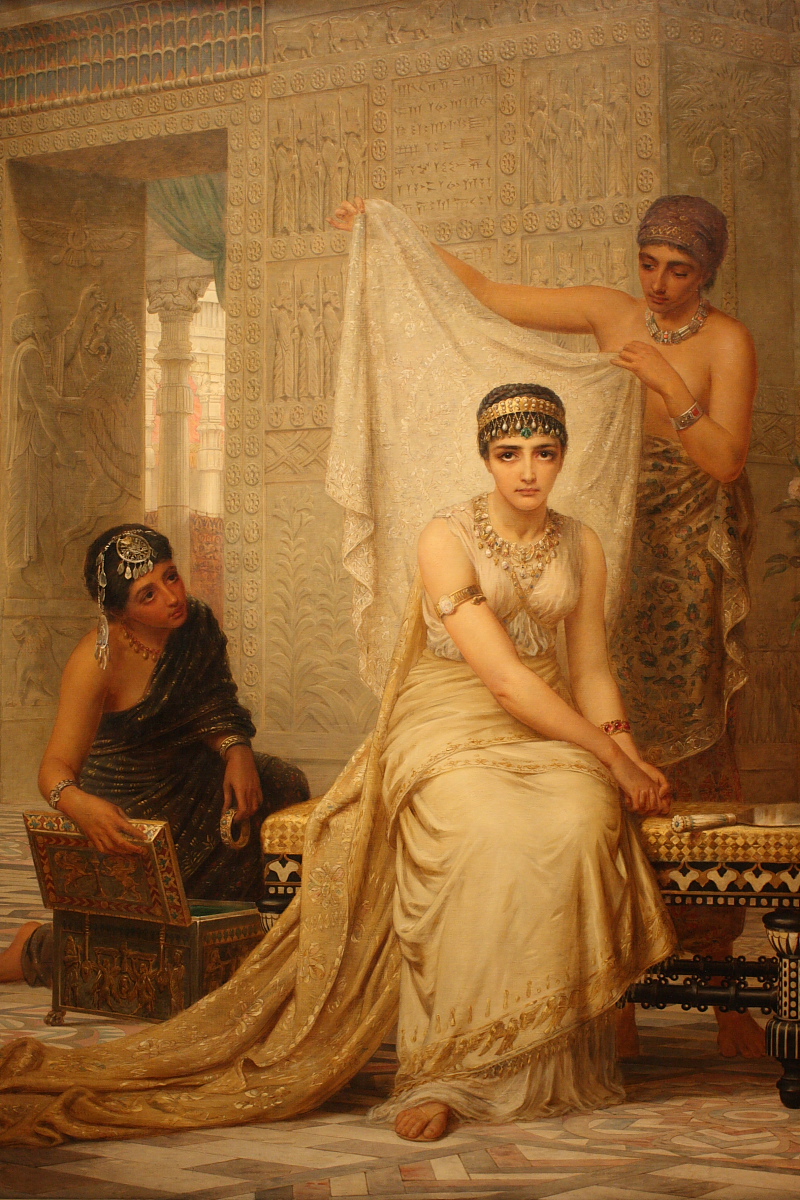

The odd thing about the Book of Esther is that it starts as if it’s going to be a love story. The relationship between Esther and Xerxes is at the center of the book, vital to everything that happens. And think of the story: A king, searching for a queen, chooses out of many women a girl  who is an orphan, a girl in exile from her conquered nation. It’s the sort of thing you’d find in a fairy tale.

who is an orphan, a girl in exile from her conquered nation. It’s the sort of thing you’d find in a fairy tale.

Except that it isn’t. Here is a fact all too easily overlooked: All those other girls – the ones who didn’t become queen – Xerxes kept them. This is how a girl went “in to King Xerxes”, and what happened to her afterward:

In the evening she would go there and in the morning return to another part of the harem to the care of Shaashgaz, the king’s eunuch who was in charge of the concubines. She would not return to the king unless he was pleased with her and summoned her by name. (Esther 2:14)

This passage establishes one of the key terms of the relationship between Esther and Xerxes: She was the only queen, but she would never be the only woman. He would always have his harem.

Another window is opened in chapter 4, when Esther answers Mordecai’s urging that she plead with the king for mercy on the Jews:

“All the king’s officials and the people of the royal provinces know that for any man or woman who approaches the king in the inner court without being summoned the king has but one law: that he be put to death. The only exception to this is for the king to extend the gold scepter to him and spare his life. But thirty days have passed since I was called to go to the king.” (Esther 4:11)

Much can be adduced from this. For one, Esther and Xerxes’ lives were so arranged that they would not touch unless he summoned her – or she went uninvited to him, which she did under risk of death.

Secondly, at this point it had been thirty days since Xerxes had summoned Esther – by the time she did go to see him, thirty-three days and counting. That’s how long Xerxes could go without deciding he wanted to see Esther. So she probably wasn’t his One True Love.

Thirdly, Esther believed so seriously that Xerxes might execute her that she didn’t want to go to him even with the lives of her family and all her people at stake. Again, not the stuff of true love.

I don’t want to be too much of a deconstructionist on the story of Esther. It’s a remarkable story, and Esther’s fate was not necessarily an unhappy one. Life has many satisfactions that have nothing to do with romance, and Esther enjoyed some choice ones. And, being acclimated to her own culture’s notions of marriage, she may have judged her marriage much differently than we would. We’ll never know what she thought of it, or how she felt about Xerxes.

Because the Book of Esther is not a love story.

So why is it taken for one? Because people don’t read it or, if they do, they can’t see what’s in it for what they think is in it. It’s not a matter of dishonesty; our perception of things is so easily colored by our expectations and assumptions. Call it the Esther Syndrome.

We humans are always being tripped up by this; we do it, not least of all, to each other. (How suspicious are the actions of people we don’t like!) We often do it in regard to stories – including biblical stories, as you can see with Esther.

The Esther Syn drome is at work in what gets labeled children’s stories; nothing else can explain the fact that “The Three Blind Mice” is considered a childhood staple. (Do parents even listen while they recite that ditty to their children?)

drome is at work in what gets labeled children’s stories; nothing else can explain the fact that “The Three Blind Mice” is considered a childhood staple. (Do parents even listen while they recite that ditty to their children?)

It’s at work in the stereotype of fairy tales as happy fantasies. The older fairy tales, the kind the Brothers Grimm published, are often cruel and occasionally so dark you can only wonder what demented imagination conceived them. Even the more modern versions, mercifully lightened, have their heavy moments.

I emphatically include Disney movies among those modern versions (emphatically = new paragraph). Disney is also stereotyped as being just too happy, by people who are apparently too caught up in the “Happily Ever After” ending to notice the unhappiness that came first.

Are there any famous stories, biblical or otherwise, that you think are misunderstood?

Excellent points. I once read Gladys Malvern’s novelization of the book of Esther called Behold Your Queen! Malvern puts a very innocent construction on the scenario of Xerxes trying out each new potential wife: he merely interviews the girls, and if he doesn’t think much of their intelligence or character he has nothing further to do with them. And I think the thirty days’ hiatus is put down to him being very busy. But, yeah, Occam’s Razor and all that. I think your interpretation is the more credible one.

Concerning darkish original fairy tales, I think we err in believing that young children ought to be the primary audience. They’re really more young adult fare.

Wow. That’s not completely offensive. (sarcasm) It’s been many moons since I’ve heard that much shallowness concentrated into the space of 17 seconds. Pha-reeking nominal.

Stephen — Oh my goodness. That made me laugh so hard.

About Esther – the book “Hadassah: One night with the King” does a really good job at capturing the reality of the situation, the characters, and the story.

…and then the movie “One Night with the King” messed up every plot in that book. >_<

I’ve never heard Esther called a great love story, only Ruth. Esther is said to contain “the greatest literary ironies”. Which it does.

Nursery rhymes contain some horrible things! Little Bo Peep’s sheep are all killed in the end (she finds their tails hanging in a tree). Ring around the Rosy was about dying of the Black Plague. What about grabbing the old man by the left leg and throwing him down the stairs? I mean, sheesh! (Goosy goosy gander, whither shall I wander…)

Oh, when I was in Sunday school the other day, they used A Christmas Carol as an example of “storing up treasures in heaven.” (We were using Alcorn’s Treasure Principle material). And it made me so mad, because you can only define Scourge’s transformation as “seeing things in light of eternity” if you water down the definition to the point where “horrible reputation”= eternal consequences.

A lot of people mistake the point of David and Goliath, thinking it a fable about bravely facing difficult odds. That’s not what the author intended to communicate, though. 1 Samuel 17 mentions multiple times that Goliath is “from Gath.” We see in Joshua 11:22 that the Anakim were left in Gath when the Israelites failed to obey God and fully conquer the land which He promised to give them. David’s act is less about bravery than in trusting God’s covenant promises.

Slow. Clap.

The “David faced his giant and now it’s time to face yours!” rhetoric is exactly what came to mind when I read this. Now it seems like a trope to put the David-and-Goliath account in a Biblical covenant context. But I still recall when I first heard of this seeming radical notion — in fact, I was in a Sunday school-type gathering in the large single room of my then-startup church, and happened to overhear the other group in the corner listening to a sermon-on-CD in which the pastor mentioned that the David and Goliath account isn’t primarily a how-to about you, but a how-did about God.

I guess the problem is that so often these are the stories that we learn first as children. And the plot of Esther is exciting, and the theme is a good one for children – if it wasn’t for the slightly less appropriate details… So as children we are told that the king held a ‘beauty contest’ to choose the queen, and this bowdlerised version becomes stuck in our heads.

But you don’t need to be inaccurate to be child-friendly. For example, when we did the story recently at Sunday School I said that the girls took turns to go and see the king, and he chose the one he liked best. That’s perfectly true – I just didn’t mention what they did when they were with the king! So there’s nothing false to unlearn.

Other misunderstood stories:

The Sunday School material I use persists in making the story of David sparing Saul’s life about loving your enemies. Really? In that case why did he kill Goliath? The reason David himself gives is that he must not kill the Lord’s anointed.

Another one is the virgin birth. I know this is controversial. But surely the main point of the virgin birth was that it showed that Jesus’ Father was God. Not that sex is sinful and therefore his mother had to be a pure virgin and remain so (pointlessly) for the rest of her life despite being married.

Speaking of which – telling kids that ‘Mary wondered how she could have a baby when she wasn’t married’ is just plain silly. The children are likely to be very aware you don’t to be married to have a baby – in fact it may be genuinely confusing for some, especially if their own parents are unmarried. When a leader in our club said something similar, the kids scornfully said, “You don’t need to be married to have a baby!” For my young Sunday School kids I just omit that bit altogether – The angel says she will have a special baby who will be God’s Son; Mary wonders how this can happen; the angel says by the power of the Holy Spirit. For older kids I’d probably say something like “Mary was very surprised. She knew a woman can’t have a baby on her own – it needs a father. But it wasn’t Joseph’s baby. How could this happen?” They can then interpret this according to the knowledge they have.

I would dispute much of what you wrote, but your heart is in the right place. If I had to think of misunderstood (whether by laziness or reading too much of self into it or simply not entering into the text fully for other reasons) stories, I’d go with the gospels. Though in this case my surmise is they are misunderstood because bits and pieces are taken out and magnified, and the troubling parts forgotten. If they’re read at all.

I can add from my own experience if I do not understand what an author is doing, I may not value it. I wrote Jhumpa Lahiri off until I read an article suggesting the story collection of hers I’d read was putting forward the experiences of immigrants and the (in many cases) hybridized first generation Indians in the U.S. Then I got it. At least, one aspect of what she was going for.

I’ve answered your question. My question to you would be, “What do you make of Esther?” If it’s not about romantic love (I’ll give you that), what’s it about?