Speculative Faith Reading Group 2: Meeting Mr. Tumnus

Community reading. Many Christians have forgotten this lost art. Instead they presume we show up at church to sing, listen, mingle, eat, and toss cash and checks into oddly shaped baskets — but reading the Bible? That’s something you do by yourself, in your Quiet Time, presumably just before Coloring Time and after Apple Juice and Goldfish Crackers Time.

Community reading. Many Christians have forgotten this lost art. Instead they presume we show up at church to sing, listen, mingle, eat, and toss cash and checks into oddly shaped baskets — but reading the Bible? That’s something you do by yourself, in your Quiet Time, presumably just before Coloring Time and after Apple Juice and Goldfish Crackers Time.

Thank God it seems we’re recovering the lost art of reading God’s Story together, as church congregations (I hope without also losing the art of personal Scripture study). Yet what about other books? Should other storytelling, inspired by His Story, be only individual?

I think not. For Christian fiction, which is intended to challenge, entertain, encourage and flesh out the Gospel for readers, we need to recover community reading and discussion. We’re not “Lone Ranger” Christians here (a bad comparison, by the way, because the Lone Ranger had Tonto). So why grab a book like the classic fantasy The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, retreat to a bedroom, and then only talk about it briefly or on the internet?

If we truly believe such a story glorifies God, and that reading and enjoying it is an act of worshiping Him, then we shouldn’t keep that to ourselves. Enough of “hipster”-like niche mindsets. Enough saying “we’re weird.” And enough defensiveness. People love this stuff!

Last Saturday I was able to host my church’s first reading group for a Christian speculative story — and, as far as I know, the first event under the Speculative Faith name. Nine people, ranging in ages from 10 to older adults, discussed why Christians even read stories instead of doing good deeds or evangelism 24/7. Then, best of all, we took turns reading chapter 1.

Notes from Week 1

If you like, catch up on my chapter 1 discussion notes. And if you weren’t able to attend yourself, here are some quick observations. I hope they, along with the free study notes, help if you’re are considering starting a similar reading group at your own church.

If you like, catch up on my chapter 1 discussion notes. And if you weren’t able to attend yourself, here are some quick observations. I hope they, along with the free study notes, help if you’re are considering starting a similar reading group at your own church.

- All four younger readers, ages 10 to 13, grouped themselves in chairs on one side of the circle in my church’s cafeteria/fellowship area. As my wife later told me, at first they were into their sketchbooks. Not 15 minutes later, suddenly those were boring. C.S. Lewis: over-hyped among Christians, but for good reason. His appeal is timeless.

- After summarizing a Gospel-driven view of story enjoyment, we held a “casting call” to read the book aloud. Together we ended up reading all of chapter 1. Edmund: a 13-year-old boy. Lucy: a female college student. Susan: a mom. Tumnus (in his last line of the chapter, and first line of the book): a male college student, whose exasperated delivery of Tumnus’s “Goodness gracious me!” sent the room into laughter and then applause.

- (I personally have dibs on Aslan when he arrives, and there will be a Patrick Stewart impression. Why Sir Stewart did not voice the Lion in the recent films, I have no idea.)

- We’d forgotten that in one edition of LWW, when the children are discussing outdoor exploring, Edmund exclaims that they might find “foxes!” and Susan exclaims “rabbits!” But in a later and American edition, Edmund says “snakes!” and Susan says “foxes!” (New copies have since reverted to the original British edition.) I am not sure why the change was made, but I suspect it has something to do with fairy-tale associations of foxes — their deviousness and slyness — being lost on American readers.

- Either way, this line tells us something about Edmund, and, as I suspected, means Lewis planned this. That’s contrary to readers who say his earlier Narnia characters were not well-developed. In fact, I can recall, before I knew there was any word change or that some thought the Pevensies shallow, thinking it suspicious that Edmund likes snakes.

- Note to self: the group needed more readings of relevant Scripture before reading LWW. For instance, we explored the topic of exploration, discovering the unknown, and why that honors God. One reader pointed back to God’s creation mandate in Genesis 1. In the next meeting, we’ll be sure to read that aloud. Thus we will make absolutely sure we’re not trying to justify our story enjoyments with mere spiritual talk, but with the Word.

- We didn’t get to chapter 2, about Mr. Tumnus — and other evidently unsavory figures! Thus my editing of that portion from last week’s column, and the restoration of that material here. I’ve also added more, to flesh out what could be a very tricky topic …

Week 2

Signs from the Epic Story

Read Genesis 1: 28-30. How does this inform our enjoyment of stories (even though only food and growing things are mentioned there)? How is this “creation mandate” changed, but not replaced, by the Great Commission (Matt. 28: 18-20)?

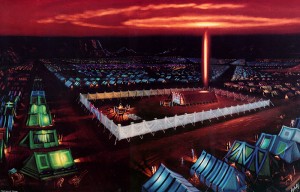

Read Genesis 1: 28-30. How does this inform our enjoyment of stories (even though only food and growing things are mentioned there)? How is this “creation mandate” changed, but not replaced, by the Great Commission (Matt. 28: 18-20)?- Read Exodus 28: 2-5. Why would God ask His Old-Covenant people to make priestly garments “for glory and for beauty”? In the rest of those chapters, why did He care to go into so much detail about tapestries, props, costumes, and architecture? It almost sounds like He is putting together a theater “set”! Next, read 1 Cor. 10:31 and James 1:17. How does these remind us that this isn’t just an Old-Testament idea?

- Now, read Deuteronomy 18: 9-14. God is very specific here about the things He does not want His people to do. What do all these words mean? What do they have in common? (Answer: they are pagan methods of trying to control your life and predict the future.) How are they different from how God says He will reveal His Word, in the next verses?

Chapter 2: What Lucy Found There

Chapter 2: What Lucy Found There

- (Break to read excerpts from the second chapter.)

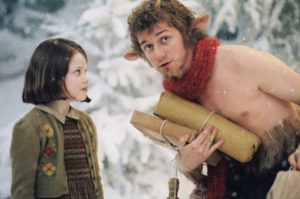

- Here we meet the famous Mr. Tumnus. Is he a good or bad character? Do you remember how you felt about him at first, and then at the chapter’s end? Was your reaction much like Lucy’s? What does this tell us about Lucy and how she sees things?

- Consider this person’s website (to be only summarized for younger readers). In Greek mythology, fauns were evil creatures who did nasty things to people, including girls. Based on this, how are we to think of Lewis using a pagan creature, a “faun,” in this way? Is that okay? Can we overlook it so long as we know the story is a Christian one?

- To make matters “worse,” what are “nymphs” and “dryads”? (Nymphs are female spirits of nature or waterways, and dryads are female spirits of trees.) Who are “Bacchus” and “Silenus” whom Tumnus mentions (pages 15-16)? You might want to look them up (do it carefully, because the Greeks liked to show them running around without clothes).

- Dionysus was a made-up Greek god. Pagan worshipers made him into the central figure of their cults. He runs around without clothes, surrounded by fangirls, and makes everything wild and crazy. He is the “god of wine, theatre, and ecstasy.”

- Silenus was Bacchus’s sidekick. He rides around on a donkey and is usually drunk.

- In fact, their mention here is a foreshadowing of their arrival in Prince Caspian. (Spoiler.) When Aslan is restoring Narnia again, they show up directly, with wine and fangirls and hollering and craziness and all. This makes things decidedly awkward for some readers. To date, they’ve never been in the movie versions.

- Should we also be concerned about these pagan characters? If not, why not?

- What about the “White Witch”? God abhors the kind of witchcraft that follows after the wicked and seeks to predict the future apart from His appointed prophets (Deut. 18). Does it help you to know — at least for now — that the Witch is the story’s villain?

- (Some partial answers about the “witchcraft” or “magic” questions.) If you are personally tempted to use imaginary “magic” in stories to try to control your life or tell the future, then you need to put away the books because they are a “stumbling block” for your weak conscience (1 Cor. 8 – 11:1). You may need to repent of your sin, asking God to deal with the sin that comes not from a book, or from hearing about someone else’s sin (or a thing that only looks like it could be sin), but from your sinful heart (Mark 7).

- But if you are not tempted, or do not make that association, then you are free to read and enjoy the story. Only be careful that you don’t seem to be saying to someone else that you’re fine with sinning, and so make another person fall into sin (1 Cor. 10).

- A hint: what does Tumnus say about the “four thrones”? (If you’ve read the book, you know who fills those thrones. Like the Creator in Gen. 3:16, Lewis is foreshadowing his happy ending.) Does he seem to believe they will be filled and the White Witch will be defeated? Does he also seem to doubt? What about how he views his old father?

(Answers.) What Lewis does with Tumnus is exactly what he does with other “pagan” creatures in Narnia. He redeems them. He takes these fun and imaginary creatures from their pagan stories, which are well-written but have some anti-Biblical themes, and says No, you can’t have it! This belongs to God! We see this later in Prince Caspian with the pagan figures Bacchus and Silenus, and we see it here with Mr. Tumnus. He makes the right choice, based on his hope in the prophecy and likely in Aslan himself. (That’s why I love how in the 2005 film, Aslan appears in the fire and roars angrily, which prevents Tumnus from completing the sinful action he had planned.) Instead of following after old “fauns” originally made up for tales of wickedness, Tumnus is redeemed for Aslan.

(Answers.) What Lewis does with Tumnus is exactly what he does with other “pagan” creatures in Narnia. He redeems them. He takes these fun and imaginary creatures from their pagan stories, which are well-written but have some anti-Biblical themes, and says No, you can’t have it! This belongs to God! We see this later in Prince Caspian with the pagan figures Bacchus and Silenus, and we see it here with Mr. Tumnus. He makes the right choice, based on his hope in the prophecy and likely in Aslan himself. (That’s why I love how in the 2005 film, Aslan appears in the fire and roars angrily, which prevents Tumnus from completing the sinful action he had planned.) Instead of following after old “fauns” originally made up for tales of wickedness, Tumnus is redeemed for Aslan.- Redeeming myth, magic, and other things that people think irredeemable will be a key concept in this reading group. How about you? Were you “pagan” and evil (Eph. 2)? What did Jesus do to redeem us anyway? How does that make us feel, and how can it help us redeem other things, as Lewis did with fauns, fairy tales, and fantasy fiction?

I love reading these notes, and can’t wait for more.

You have good points, with my only statement being a caution about those who read the next book. The characters WERE well-developed, but there is little evidence that Lewis intended as early as PC to have Susan turn from Narnia.

My thoughts on the novel are being saved for when you reach that point.

This could be related to the sense of communion with nature that is often evoked in good fantasy, and which Tolkien seemed to think was an integral part of fairy-stories. Nature has been given to us to “subdue.” I wonder if “subduing” nature can include casting it in our own image by inventing all the mythical and fantastic creatures that are close to the heart and spirit of the undefiled land — Fawns, Elves, and all the rest.

The craftsmen who were instructed to make the “holy garments” used the raw material of the earth (gold, etc.), things put under the dominion of man in the Genesis passage. By taking the natural material and then making something out of it, the craftsmen were sort of personifying the elements of Earth itself, bringing out the beauty that they saw by the creativity that God gave them. So, there is a sense of genuine communion with the Earth and with nature, and it’s not pantheistic or “pagan” in any way.

I agree with your explanation of why those things were prohibited. The difference is between communing with nature and trying to subvert nature (loosely defined as God’s ordained order) for one’s own purposes. “Good magic” (in the sense of our fantasy fiction) should be in subjection both to the spirit and the external workings of nature — and to the Creator of nature.

The next verses are a prophecy of the coming of Christ, the fullest revelation of God. Although His coming was supernatural according to the ordinary meaning of “natural,” that doesn’t mean He broke the laws that God ordained, rather He was supernatural, natural and beyond natural, the true essence of Nature as the way that God ordained things to be. And of course, Christ’s Incarnation was the great breakthrough of the fantastic to our world.

The four children are Messianic figures to Narnia, in more general way than Aslan is. Aslan might represent the divinity of Christ, but the children better represent His humanity and his role as the fulfillment of prophecy and destiny.

The humans are coming into the land of magic to redeem that magic, perhaps redeeming those pagan myths, as you suggest. The magic has gone dark, and the four children are the Chosen Ones who bring back the Light, while Narnia’s magic itself serves as their own light. Lucy is as fantastic to Tumnus as Tumnus is to Lucy.

Do you believe that Jesus was also the generic fulfillment of the pagan Gentile myths, while specifically fulfilling the promises given in the Old Testament? Can Bacchus, a twisted perversion of the Devil though he may have been, have had something of Christ in the mythology associated with him. And now that Christ has come and died and risen, now we can identify the true glimpses of Christ that existed in all the false gods and rejoice in them, depriving the Devil of his own toys?