‘Inside Out’ and Upside Down: Sorrow As A Symbiote

“The movie is set in the mind, not the brain,” says Pete Docter, progenitor and director of Pixar’s long-gestating Inside Out. “There are no blood vessels and dendrites — it’s a bit more abstract.” And yet the analogous architecture that comprises the mind of eleven-year-old Riley (voiced by Kaitlyn Dias) — by turns ephemeral, labyrinthine, and even cubist — strikes one as more accurate than many prior attempts to visualize what goes on in these heads of ours. It’s an exploration fraught with peril, and not just of the favorite-character-might-fall-off-a-cliff variety: your assumptions about reality itself may be shaken by this direct broadside to Disney’s Ethos of Wish-Fulfillment. As it turns out, by knowing ourselves we uncover truths both beautiful and hard.

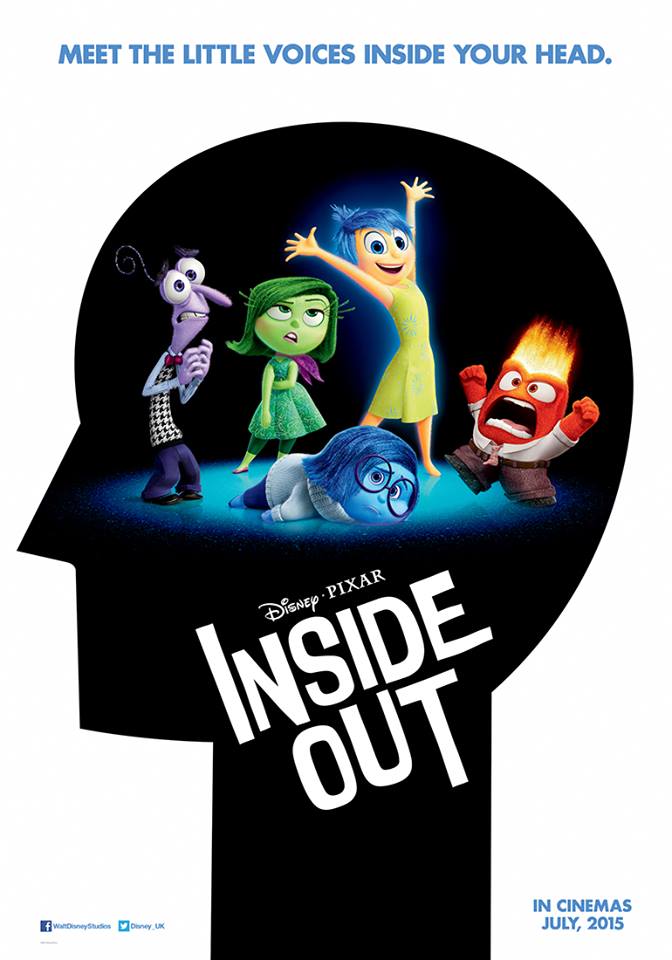

The tale begins with a flash-bang setup akin to that of Up, Docter’s previous feature. Riley is a happy girl who loves her family, her friends, and her home in Minnesota. The supervisory emotions of her mind are dominated by Joy (Amy Poehler), an effervescent Pollyanna who rides herd on Anger (Lewis Black), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), and Fear (Bill Hader). Life is good.

And then she’s moved to San Francisco.

Docter and his creative team turned to cutting-edge psychology to pare the spectrum of human emotion down to its most fundamental elements. The five anthropomorphic emotions in the headquarters of Riley’s mind exert total control over her actions — their interactions embodying her inner debates. How should she react to her new room? Her father’s distraction? The food on her plate? And what about the homesickness that brings her to tears in front of her classmates? Riley’s parents, though loving and attentive, can’t see into her psyche. Her friends all live far away. The transplantation has precipitated a crisis of identity, and Joy is losing control.

Then one day the unthinkable happens: Joy gets sucked out of headquarters and deposited in the maze of long-term memory outside. She was trying to protect Riley’s core memories — five impressions of her past that form the substance of her personality — from Sadness, who’d developed a strange fixation for the little golden orbs, and then everything went wrong. Now she’s trapped with Sadness in a land of prior thoughts and feelings, and headquarters is at the mercy of Anger, Disgust, and Fear, emotions who can’t imitate Joy no matter how hard they try.

Preteen drama ensues.

During its second act the story flags at times. Docter is no Brad Bird, and his script receives scant help from his characteristically pedestrian cinematography. But despite some doldrums and a surprisingly glaring plot-hole (don’t look for it — it’ll just make you sad), there is wonder here, and hilarity, and tension to spare as Riley, bereft of Joy, withdraws further and further into herself, her Islands of Personality crumbling one by one. It’s a race against time for Joy and Sadness as they careen across Riley’s mental landscape. But for things to be set right, something deeply counterintuitive must go down.

From this point on, Dear Reader, I must forge ahead into spoilers. If you’re content to trust me, then know that Inside Out pitches its philosophical tent about as far from Disney’s typical hedonism as the brain is from the stomach, and then go see this wonder for yourself. If you require more specific reassurances, then read on.

It is not Sadness who must be brought low in order for Riley to thrive. Neither is it Anger, Disgust, or Fear. No, the film’s chief character arc belongs entirely to Joy, who finds out that she knows far less about existence than she had ever assumed. When push comes to shove, Joy doesn’t know what to do with the pain of loss. She’s unable to acknowledge it, and thus incapable of overcoming it. But Sadness harbors no such fear. She gazes steadily into the face of another’s bereavement, and says, simply, “That’s sad. I’m sorry.”

Joy, witnesses to the transforming power of this new approach, relinquishes Riley’s core memories, allowing them to be colored by Sadness. Riley weeps, confesses her rebellions, and seeks consolation. Her acceptance of sorrow is the key that unlocks her personality from its terrible limbo. Unable to forestall change, she must make peace with the bittersweet past. Only then can she be happy again.

Now if only Disney’d spent a couple of generations feeding kids with this instead of its easily-swallowed, if-you’re-not-happy-something’s-wrong slop.

Emotionally, Inside Out runs the gamut. There are scenes that left me in tears, and scenes that had me laughing from my gut. Just watching the interaction between Riley’s emotions, along with that which occurs between the emotions of those around her, is well worth the price of admission. And Pixar, in positing a symbiotic relationship between joy and sadness, may flip the assumptions of many viewers upside down.