Chariots, Horses, and Aircraft Carriers are No Match For ‘Godzilla’

“The arrogance of man is thinking that nature is in our control, and not the other way around.”

This line of dialog from the latest cinematic incarnation of Japan’s premier daikaiju, delivered with characteristically understated intensity by actor Ken Watanabe, neatly encapsulates the film’s thematic thrust. Theatergoers take warning: if you stomp into Godzilla rarin’ for a rip-roarin’ monster hunt in the vein of Roland Emmerich’s 1998 cheese-fest, or expect the titular creature to demonstrate humanly-apprehensible motives, you may emerge slightly dazed. This primeval beast has an agenda all his own, and it’s all either we or the film’s human protagonists can do to keep pace.

Largely unconcerned with scientifically-quantifiable explanations and all other forms of explicitness are screenwriter Max Borenstein, who’s cited Jaws as a tonal template, and director Gareth Edwards, whose 2010 indie thriller Monsters showcased his ability to cultivate large-scale suspense without relying on CGI. Here he sparks the slow-burning tension with a mysterious meltdown at a Japanese nuclear power plant in the late ‘90s. It’s a sequence which establishes three crucial things: the drama is human, the stakes are real, and the threat is beyond comprehension. In Godzilla, death is by no means relegated to redshirts and hapless townsfolk, but neither is it distributed cheaply. This is a movie that gives us reasons to care. Its characters are introduced and developed in light of their relationships — father with son, husband with wife — and it is the roles of son, husband, and father that commit Ford Brody (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), an explosive ordinance disposal technician in the US Navy, to the fight of his life against rampaging titans.

And yes, that’s a plural. Godzilla himself eventually appears not as an unprovoked assailant, but as an “alpha predator” hunting a pair of MUTOs (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms) awakened by the actions of man. Subsisting on radiation and communicating by means of electromagnetic pulse echolocation, the skyscraper-high MUTOs, male and female, gouge intersecting swaths of destruction across the Pacific Ocean and America’s West Coast en route to an amorous tryst, stalking with a long-limbed malevolence reminiscent of the tripods in Spielberg’s War of the Worlds.

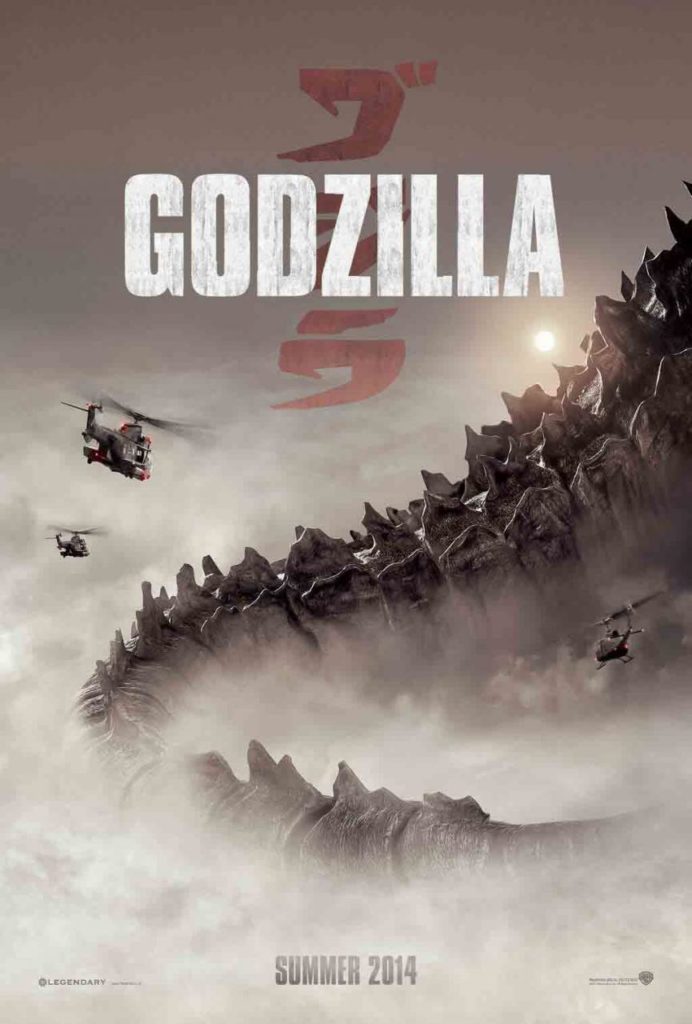

For creatures of this scale, human opposition provides a mild annoyance at best. The world’s mightiest electrically-dependent military is rendered powerless through organic EMP blasts, then obliterated piecemeal with blunt force trauma. This is no Pacific Rim; humanity possesses no advantages in weaponry. The scope of the action — when action at last becomes the film’s primary mode — is staggering. There’s a weight — a solidity — to the movie’s moving mountains that bashes in one’s breath. Only hubris would assume man capable of contending with such monsters.

And that’s the point. It’s no coincidence that, in the film’s climactic confrontation, it’s all the humans can do to mitigate the fallout from their own futile schemes while leaving the giants to duke it out among themselves. But this fundamental impotence doesn’t reflect despair or fatalism on the part of the filmmakers — no, were that the case, they wouldn’t impel us to care so deeply about the outcome or cheer so unselfconsciously at moments of hard-earned catharsis. Instead, it’s an acknowledgement that, even in this world we seem to know so well, there are things beyond our control, forces beyond our ken, and monsters beyond our mastery. Ultimately, we can’t depend on our own strength for survival.

It’s a truth with which Christians should be intimately familiar. But even so, it sometimes takes a Godzilla to bring to mind our reliance on God.

Finally got to see this. The Watanabe quote is odd because the creatures aren’t a judgement of nature on man. They are explained as eating radiation that naturally existed during the prehistoric days. It was more our ill luck we happened to harvest that power. The MUTO are also traditional animals who belong to an old ecology. Our nuclear plants are the equivalent of raising feed animals for them.

The EMP honestly felt like cheating. A lot of this movie tended to cheat things. It cut off battle scenes, and really didn’t give much explanation of why that made sense. Given the reproductive potential and sheer staggering size of the monsters, you wonder how any ecology could have developed at all. The EMP was just there is we didn’t see big battle scenes with the army. Watanabe trusts Godzilla and opines on what he is without any real reasoning behind it. Kind of half-assed a lot, and it’s weird to see lower budget G films have more of a consistent worldview behind them.