A Storyteller Sings In ‘The Way Of Kings’

Every decade or so, there comes along a work of fiction so masterful that it refreshes our assumptions about storytelling and heightens our ideals of excellence itself. Often the sea change is unforeseen. No one knew they needed The Lord of the Rings until Tolkien wrote it. That single glimpse of the sublime awakened in readers a hunger that has yet to subside. Opportunistic imitators sprang from the heavily-carved woodwork, eager to sate this new appetite, but the age of the Elves was already over. In a tragic yet predictable irony, the very literary event which proved so seismic at the time had relegated its aftershocks to relative insignificance. So definitive was Tolkien’s vision, so comprehensive his execution, that not much had been left to say. Or so it seemed. For decades, no genre has been in greater need of refreshment than that of high fantasy, which, overawed by Tolkien’s legendarium, has found it gallingly difficult to emerge from the shadow of Middle-earth.

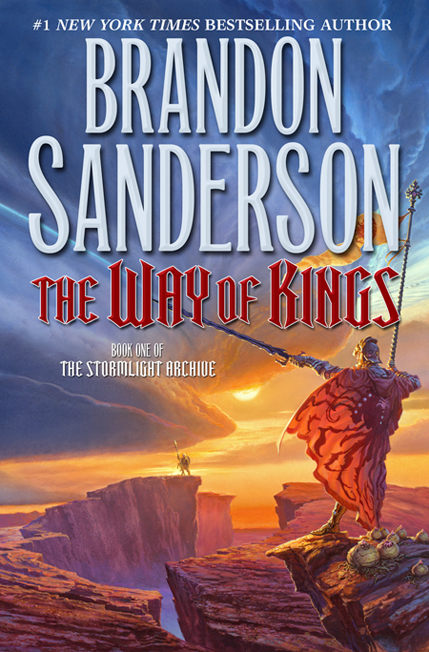

Enter The Way of Kings, thousand-page behemoth and first installment in The Stormlight Archive, a planned ten-book high fantasy cycle from prolific genre author Brandon Sanderson. As the pinch-hitter for The Wheel of Time following Robert Jordan’s death, Sanderson is no stranger to the tropes of traditional fantasy plotting and worldbuilding. Indeed, his own original novels tend to rely on his audience’s familiarity with such tropes in order to pull off elaborate head fakes. With Sanderson, innovation is the name of the game, whether it’s in regard to setting (he prefers cities to wildernesses — gasp!), plot (unconventional setups, whiplash twists, unforeseen-yet-inevitable resolutions), or characters (their appearances tend to be deceptive, unless you’re meant to think so). He constructs magic systems so complex and internally consistent that his stories sometimes read like medieval science fiction, and his universal Laws of Magic should be taken to heart by every fantasy writer. I’d already become a huge fan of his work prior to The Stormlight Archive. But even amidst an exceptional repertoire, The Way of Kings stands out. It’s the single greatest fantasy novel I’ve read since The Lord of the Rings.

I’ll give you fair warning, dear reader: this ain’t no “balanced” critique. I have no criticism to lob — only praise. Also, it just so happens that the even-longer follow-up novel, Words of Radiance, debuted this very month. What a convenient excuse for me to rave!

Our story unfolds on the world of Roshar. It’s a desolate continent of bare rock scoured every few weeks by ferocious highstorms — hurricanes on steroids which come boiling over the eastern horizon and aren’t spent until they slam against the mountains of the distant western seaboard. It’s a brutal world, one whose flora, fauna, and human civilizations have been forced to scrabble for survival in the clefts and sheltered fissures. Grass withdraws into the ground when approached. Animals — from the minuscule to the monstrous — are fashioned after the crustacean template. Mankind’s religion, culture, and architecture has adapted over millennia to the environment’s hostility. Inspiration for such a world first struck Sanderson as he watched waves surging through a tide pool. Roshar is that precarious ecosystem writ large. For its residents, resiliency’s non-optional.

But for one resident in particular, resiliency won’t be enough.

His name is Kaladin. Trained as a surgeon by a pacifist father living in the warrior-caste nation of Alethkar, he wagered a promising future in a bid to protect his family, then lost both in a calamity that’s dogged him to the edge of suicide. Now enslaved far from home in the encampment of a vengeful expeditionary force, Kaladin must face his greatest trial: the struggle between hope and despair on the battlefield of his own soul. Much depends on the outcome. For not only is he a natural leader with the power to inspire those around him, to become the hero behind whom they rally, but Kaladin unknowingly possesses the key to a renaissance of magic that will shake the certainty of the wise and the security of the great.

Too bad his will is broken. Too bad he’s given up.

But at least he’s not alone. A peculiar spren — one of the ubiquitous elemental spirits that seemingly inhabit everything on Roshar — has become his shadow. Her name is Syl. She’s a sprightly, sensitive optimist. Though invisible to others, her persistent antics demand Kaladin’s attention. And, as she acclimates to his presence, their friendship begins to have unsettling repercussions. As though he needed anything else to set him apart.

For Kaladin isn’t like other men. His companions call him “Stormblessed” and think he’s good luck, but he believes, with good reason, that he’s cursed to watch them all die. And what good are his skills, brains, or initiative when fate routinely spits in his face and brings all his efforts to naught? What else can he do but withdraw into a shell of indifference like an unharnessed chull hunkering down for a highstorm? Syl keeps nudging him toward hope — urging him to keep trying, to keep investing his energy in others — but now more than ever he sees hope as an illusion meant to keep his legs pumping in service to the powerful. Survival is the best he can hope for now. For Kaladin Stormblessed has found himself in the waking nightmare that is Bridge Four: a death-row gaggle of slaves forced to shoulder a massive wooden platform while running ahead of Alethkar’s armies across the crevasse-scored Shattered Plains, stronghold of an inscrutable humanoid race that claimed responsibility for the Alethi king’s assassination five years prior. It’s a lunatic tactic in a war that doesn’t make sense. And Kaladin isn’t the only one who’s confused.

Commanding one of those armies is Dalinar Kholin, Alethi highprince, brother to the slain king and uncle to the current one. His reputation is terrifying, his accomplishments manifold. But he’s worried. The death of his brother at the hands of an unstoppable assassin with the power to manipulate gravity has, ironically, turned his life upside-down. He was drunk at the time — wallowing in revelry while his lord struggled for his life. He’s vowed to never again incur such shame. He’s begun studying “The Way of Kings,” an ancient text once revered by the legendary Knights Radiant. Now lost to history, the Radiants were powerful warriors who kept the peace and drove off the Voidbringers — horrific entities ravenous for the end of the world. Or so it is said. What the Radiants really were no one knows, for they disbanded and vanished long ago, abandoning their charge for reasons still unclear. And now Dalinar is discovering that what they apparently believed runs contrary to everything his culture exalts.

He’s a conflicted man, is Dalinar. What’s worse, he might be going mad. For the past few months the arrival of each new highstorm has plunged his waking mind into a vivid vision of some ancient historical event, then spit it back into consciousness with the same ringing imperative: “Unite them!” He thinks the visions are messages from the Almighty, the supreme Alethi deity, but he can’t be sure. And, between his abrupt change of habits and hallucinatory ‘episodes,’ everyone around him thinks he’s going soft in the head — succumbing to senility or religion. Even his own son and heir doubts his competence. Dalinar’s at a loss as to how he can possibly effect societal change while simultaneously alienating himself from society.

Meanwhile, half a world away, a young woman is about to betray her conscience to avoid similar estrangement. Her name is Shallan Davar, and she’s traveled across land and sea to apprentice herself to the atheistic scholar Jasnah Kholin, niece to Dalinar, a woman as acerbic and elusive as she is learned and powerful. But Shallan isn’t looking for an education — what she seeks rests lightly upon the back of Jasnah’s palm: a soulcaster. This magical transmuter of matter has the power to restore the Davar family fortune, which upon the death of Shallan’s father was revealed to have as its source a now-broken soulcaster of his own. Unless Shallan can find a way to steal a new one, she and her brothers will have to face their father’s creditors empty-handed — and their father kept frightening company. But can she really justify such a treacherous theft, especially when it becomes apparent that Jasnah’s research could shed disturbing new light on the mythic Voidbringers? As Shallan grapples silently with competing motives and a secret shame from her past, she edges ever closer to a terrifying encounter that will alter her perception of reality.

The board is set. The pieces are moving. And none moves more erratically than Szeth, the infamous Assassin in White who murdered of the king of Alethkar despite that man’s supernaturally powerful armor and weaponry. Now, exiled by his own people for a mysterious crime and condemned by his religion to submit himself to whoever obtains the sacred stone he carries on his person, Szeth has become a black market commodity, an instrument of destruction passed from hand to bloody hand, wreaking havoc wherever he goes. Unfortunately for Szeth, his unique skill-set didn’t match his once-gentle soul. And as his body-strewn path snakes across the land, he learns the hard way how barbaric is his fellow man. He’s been trying to keep a low profile, but it’s only a matter of time before he’s snapped up by someone with an agenda more ambitious than those of the small-time crooks and gangsters who’ve thus far exploited his services. And when that happens, the world will change forever.

Over the preceding ten paragraphs I’ve recited a lot of strange names and dumped a lot of intricate data. Just distilling the scope of this story into some semblance of concision has proved a daunting task. But if such an approach has left you with the impression that The Way of Kings is some bloated monstrosity of exposition or pretext for self-absorbed worldbuilding, let me assure you that you have nothing to fear. It’s part of the author’s charm that he can whisk readers through a dense, labyrinthine plot as though it were light as a thriller. His pacing is incredibly precise, his characters wonderfully real, their arcs deeply satisfying. By the time I reached the inevitable ‘Sanderson Avalanche’ in which the slow-burning tension exploded in an overwhelming cataclysm of frenetic conflict, I was reading at a breakneck pace, oblivious to the outside world, teetering on the edge of tears. Rarely have I been so moved by a novel.

But while The Way of Kings is an epic chronicle of despair and hope, loss and discovery, tragedy and triumph, it’s also an introduction — the establishing shot which sets the scene for all forthcoming action. As I flipped the final page and collapsed — exhilarated, emotionally wrung-out, reeling from revelations that’d rocked my world — the fact that I’d only advanced a tenth of the way into the larger narrative was almost impossible to comprehend. I’d just experienced a Tolkienesque eucatastrophe. How could there be any more wonder left where that had come from?

And “wonder” really is the key to this story’s power.

I lingered earlier over the particulars of the setting not because The Way of Kings reads like some kind of fictional field guide, but because its environment really does count as a character in and of itself. Its presence is felt in every scene — a subtle pressure on the edge of consciousness, a weight of mystery just beyond reach. The setting and plot are integrated. Sanderson typically steeps his worlds in forgotten magic, but on Roshar I get the unsettling premonition that nothing I see or experience exists apart from the influence of hidden forces beyond my ken — that, like a scholar sifting the endless library in Kharbranth, City of Bells, I can parse dust-cloaked tomes and squint at puzzling fragments until the end of time and still draw no closer to an epiphany without devouring the next installment in the series. Roshar is a big place, and full of secrets.

But I know they will all come to light.

I say this because Sanderson is, in my opinion, the best kind of storyteller: one I can implicitly trust to exercise sovereignty over his own sub-creation. Nothing about his narration is random or haphazard. In The Way of Kings, every single element of the overall reading experience cries out “Design!” From its five-part structure titled after the lines of an ominous palindromic poem, to the enigmatic epigraphs which begin every chapter and defy comprehension until context has reached critical mass, to the all-too-brief interludes which deposit us in exotic corners of the world just in time to catch some obscure hint about the true nature of things, this novel exhibits a holistic symmetry that will delight artists and engineers alike.

With such suffusive intentionality in mind, the plot functions on three levels. First, there’s the foreground plot: the present-tense travails of the characters, the short-term challenges they face. It’s this level that absorbs the majority of a reader’s emotional energy during an initial read-through. And in the foreground of the foreground stands Kaladin. His are the flashbacks, his the most intimidating tasks, his the strongest arc. The Way of Kings is his book, just as its sequels will belong primarily to others. But a glance snuck over his shoulder will reveal so much more.

The second level is the background plot: the larger story of Roshar as a whole, the inertial progression of nations, cultures, and scientific knowledge. Hidden forces are hard at work behind the scenes, setting in motion events whose reverberations will, eventually, be felt by every living thing that claws for survival upon the face of the world. During my initial read-through, I patted myself on the back every time I picked up on even the smallest hint of what was really happening on this secondary level. But it wasn’t the biggest picture.

The third and final level (warning: geekery ahead!), is comprised of the Cosmere-level plot. Other than a vague awareness that most of Sanderson’s full-length fantasy novels take place in a shared umbrella universe — the Cosmere — I hadn’t a clue how such knowledge could color my perception of specific characters and events until I began supplementing my second read-through with the analysis and discussion of fellow Sanderson fans. Suddenly a whole new world of subtextual meaning opened up before my feet, and I realized with shock that the story’s stakes were even higher than I’d assumed.

But for the Sanderson newbie, there’s no need to collate oblique inter-book references in order to savor The Way of Kings’ rich thematic substance. Its central through-line is an unflinching examination of the nature of leadership as confronted by those invested with and those stripped of authority. And when you think about it, this focus makes perfect sense. You see, Sanderson is a Mormon. And, though he’d deny injecting his stories with an ulterior religious agenda, one can’t help but notice the recurrence of certain motifs across his body of work. He seems preoccupied, for instance, with the idea of mortals attaining deity, along with the burden of responsibility that’d necessarily accompany such an elevation. There’s nothing sinister about this; it’s actually quite refreshing to observe empathetic characters grappling with the secondary and tertiary implications of their morality. Like Tolkien before him, Sanderson’s just allowing his worldview to spill over into his imagination, and, as long as one recognizes where he’s coming from, much can be gleaned from his insights into human nature.

And insights he has, because his characters behave like real people. None of them act without plausible motivation, none disappear when viewed from the side. Sanderson isn’t afraid to challenge their every belief and then allot them sufficient space to digest the questions he’s raised. By respecting his characters, he respects his readers — and it’s a respect that demands reciprocation. For instance, though he’s made it clear from page one that Roshar is a deeply spiritual world, Sanderson allows Jasnah Kholin, the story’s resident skeptic, to eloquently obliterate the apologetics of a concerned theist without incurring narrational judgement. Though we love and respect Kaladin and deplore the oppressive system under which he suffers, Sanderson isn’t afraid to demonstrate that this system sometimes understands more than does Kaladin about the workings of the world. Though it’s clear that the Voidbringers are evil, it’s not at all clear how human beings should go about resisting them. Truth is present, but it’s clouded — seen as through a dun sphere, darkly.

And what more shall I say? Time would fail me to tell of Shardblades and stormlight, of chasmfiends and gemhearts, of Shadesmar and surgebinding, of the Stormfather and the Nightwatcher. And of Hoid. Time most certainly would fail me to tell of Hoid, the most enigmatic character in the Cosmere mythos, a man with his fingers in more jam-jars than can bear rational explanation. Hours would flee fast away were I to recount the ferocious battles, tender trysts, hilarious quips, and spine-chilling epiphanies which comprise The Way of Kings. Far better for you to experience them yourself. For, in the words of a man perched upon the edge of firelight as the night draws close and strange music dies away into chasms of darkness, “The purpose of a storyteller is not to tell you how to think, but to give you questions to think upon. Too often, we forget that.”

Step onto the sweeping stage of Roshar, dear reader, and remember this truth once again.

I saw this book at my local library and passed it up. Now I’m kicking myself.

Scanning the bookstore’s fantasy/sci-fi section is a guilty pleasure of mine. I love basking in the cover art, but know the contents will likely disappoint. Not so with Sanderson.

So cease kicking thyself and spring into action, for The Way of Kings is only $2.99 on Kindle right now. That’s three-tenths of a cent per page!

You raised my hopes only for them to plummet back into the chasm. The Kindle edition is almost $11 🙁 Was it really only $2.99 for a moment and I missed it??? :'(

The page I’m looking at says it’s still $2.99. Click the link I included in my earlier comment and you should see the same thing.

Nope. 🙁

Can Amazon change the price based on what your country of origin is? I’m on Amazon.COM not .CA but my IP address is Canadian and Amazon.COM knows that… Wanna gift it to me and I could paypal you? o:)

That sounds fantastic! I just can’t commit to 1k pages, though. It takes me 3 solid weeks to read a book that long.

Yeah, it took me three weeks, too. If you’d prefer to ease into Sanderson fandom rather than plunging into the deep end straightaway, I recommend his Hugo-winning novella The Emperor’s Soul, which I finished in two evenings. It’s pure gold.

I have decided to read this and Words of Radiance. I gave up the first time about a third of the way or so through as the constant breaking of Kaladin was too depressing for me, but I’ll try it again as I hear that he actually is rewarded for doing the right thing eventually.

The only problem that I would say is that I think that Sanderson gave a tad TOO much focus on Kaladin’s sorrow and brokenness, at least what I read before. Granted the book is almost twice as long, but in Mistborn: The Final Empire, the story skipped forward a bit, so we saw Vin’s development of trust in Kelsier and the others more quickly. That is still my favorite of the Mistborn trilogy, as I must admit I do like more idealistic stories, and I despise depressing books. But his other works are such that I’ll give it a try.

Please do not compare a brilliant author like Sanderson to the late Jordan. God rest his soul, but Jordan was an overly wordy guy whose prose was incredibly unwieldy. To quote tvtropes.com, you’d be drunk if you played a drinking game and took a swig for every time Jordan described Aes Sedai “serenity” or the design of the girls’ dresses. Sanderson is incredibly economical in the way he uses words. Nothing is there to be wordy and he makes every word necessary. With him, his works are filled with necessary content, while with the late Jordan and many, many other authors, their works are arguably a third or more of filler.

So I am going to try this again. I just have to get through the depressing parts.

As someone who finished The Eye of the World with absolutely zero desire to read even one sequel, let alone ten, I’d never dream of comparing Sanderson to Jordan. Jordan has the incredible ability to imbue his characters with powers of perpetual annoyingness, while Sanderson, on the other hand, writes about people I’m able to love with my whole heart no matter what their function in the plot. The differences are stark, and they’re all in Sanderson’s favor.

But as I wasn’t reviewing Robert Jordan, I felt no compunction to dis him. I know there’s a lot of people out there who read his stuff rather fervently, and I’d hate to offend ’em unnecessarily. Because they’ll love Sanderson, too.

As for Kaladin’s agony, it’s probably the element of the book I respect the most. Here there are no shortcuts, no loopholes, no elided timelines, no easy outs. You the reader are made to watch as your favorite character and his fellows are brutalized again and again and again and again until your genre-savvy timer has long since expired and you’re actually there with them in the chasms and on the plateaus, your hope waning, your mental fortitude beaten, your cheap confidence overthrown. Just when you think Kaladin’s finally outsmarted his circumstances, the mat gets yanked out from under him. Just as you think he’s getting a handle on things, double is demanded. Just when you think his life can’t possibly get worse, it does. It’s on the Shattered Plains that Brandon Sanderson reveals his story’s true scope. It’s a scope not of sight but of emotion, a depth not of theme but of credibility. You can’t help but sympathize with Kaladin. You can’t help but admire him. And, in the end, you can’t help but weep and rejoice as the seeds of his suffering bear fruit so glorious it’s almost painful to behold.

In The Way of Kings, victory doesn’t come cheap. It’s earned through pain and blood and sorrow and death. But there’s stormlight at the end of the chasm.

And darkness makes that light shine brighter.

I’ll give it a try since you and others have vouched for the triumph at the end. I have a natural aversion to dark and edgy, but if this isn’t that, I’ll read it. Just started today.

I will say that part of my thing is that I need a “reward” of good winning to read negative stuff. What I mean by that is that I need more than just an “interesting character profile” or an “examination of humanity”, so forth. I only made it about a hundred pages into Wuthering Heights, for example, before I chucked it.

Now that I know there is a happy scene for Kaladin, I’ll give it a try.

It’s ironic, by the by. In the aftermath of the expanded reviews here, you submit this, and I’ve been tweaking an old review of Mistborn: Hero of Ages, to submit. I think I’ll work up reviews on each of the three books to submit.

Do it! ;-D

I’ve read Way of Kings, as well as a few of his other books, and while I wouldn’t rate Sanderson on my top ten list, I second everything in this review

Yay for people who love these books too! I’m not the only one in my family who’s read Sanderson, but i’m the only one who’s read Way of Kings and i’m the one with a passion for his books. I pre-ordered Words of Radiance and read all of it in a 24-hour period, and am intending to read it again very soon.

I understand that Kaladin’s despair can be hard to read — i found it the same when i first read it. Personally, i appreciated it because it isn’t often that you find a book where the main character is allowed to come so close to breaking completely. And i found the resolution to his arc wonderful.

The Stormlight Archive is Sanderon’s finest work to date, in my opinion, and i loved Words of Radiance even more than the first book.

Like I said earlier, so long as I get rewarded with Kaladin’s happy scenes, I’m good.

24 hourse for 1,108 pages? Seriously? Wow! I wish I could read that fast. I’m impressed and kinda jealous.

If you like Sanderson, then check out Brent Weeks. Be warned that Weeks is a hard R rated writer, compared to Sanderson’s PG. Both seem to come from a Mormon worldview. ( why is it Mormons can write great fiction but Protestants cannot?)

Jim, that question has galled me for years. I’d like to believe it’s ’cause their religion is pure fiction, but, realistically, I think it has more to do with Mormanism’s emphasis on eternal influence and responsibility. While Protestants tend to visualize their afterlife through the paintstrokes of 15th-century apostates with a thing for bland cloudscapes and obese urchins, Mormons are busy imagining themselves as the kings and queens of their own planets. They’re highly motivated to wrestle with issues of creativity and leadership, since they expect to put those qualities to eternal use. But Christians? Christians expect to spend eternity singing praise mantras.

And yet we’re told we’ll judge angels (1 Cor. 6:2-3). What awaits us on the other side of death is not some kind of heavenly retirement home, but more life and activity and responsibility than we have ever imagined or been capable of shouldering before. In this one area of thought, we really do need to wake up and be more like the Mormons.

I think Catholics might disagree with you on who Protestants should emulate. 🙂

PS (and apologies for the off topic nature of this comment): how did I miss all this time that you are a filmmaker? It’s great to know there’s another person involved in the world of entertainment around here (even I’m mostly on the theatre end of that spectrum).

I work on the corporate end of the video production spectrum, I’m afraid. Feature film work is a far-off dream for me right now, but one I intend to be prepared for if its opportunity materializes. Theater is great — very different from film in some ways, very similar in others. When I was in college, we in the video production program were deeply indebted to that group of theater majors who were willing to bridge the gap between disciplines.

So, after reading all the books thus far, I think I may have picked up on something. I’ll keep this brief: I think Sanderson is trying to paint Odium as the GOD of the Bible as he views HIM. I don’t want to give too much away in case people haven’t read the books, but think about it if you’ve read them.

Might this be a better alternative to ASOIAF