Revealed: Here’s the Little Trap I Set to Expose Rotten Tomatoes

It’s high time I detail a little “trap” that I set for the website Rotten Tomatoes exactly two years ago.

For fantasy fans, the trap reveals more than the critical response to a certain movie (in this case, Justice League).

Rather, the trap result helps show us much about our flawed reliance on review-aggregate websites—that is, digital platforms that collect often-subjective creative expressions, such as movies and movie reviews, and reduce these into a simplistic binary of “fresh” or “rotten.”

First, I’ll describe how Rotten Tomatoes works, in some detail.1

Second, I’ll describe the trap, and the reasons I set it for Rotten Tomatoes.

Third, I will consider: what lessons can Christian fantasy fans learn from this?

1. How the Rotten Tomatoes website works

During 2017, I was recruited to help Christianity Today‘s website with occasional movie reviews. (This was thanks to my work with Christ and Pop Culture.)

That year I ended up writing four reviews. Three of these were for superhero movies.2

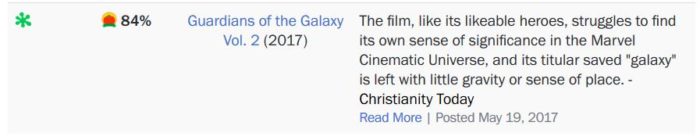

After I reviewed Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, I noticed an unexpected bonus to the job. I now had my own reviewer page on Rotten Tomatoes (only for my CT reviews). Also, they had posted my review of Vol. 2 as “rotten.”

This taught me a few facts:

- I had not requested to submit my movie-critic reviews to Rotten Tomatoes.

- This apparently means Rotten Tomatoes chooses who to count as a critic.

- More importantly, I didn’t tell them my view of the movie was reduced to “rotten.”

- That means someone at Rotten Tomatoes interpreted my review as “rotten.”

Still, I must be fair. If at that moment in May 2017, if you demanded that I call my Vol. 2 review “fresh” or “rotten,” I would have had to say “rotten.” Only under duress. Most of my review did focus on ways I felt the movie failed to meet its own goals, or contradicted its own themes. But Rotten Tomatoes didn’t ask me this question. Instead, someone else chose a quote from it. And they stuck a little “splat” icon beside the review, interpreting my creative work—itself an interpretation of James Gunn’s space-comedy film—as saying, “That movie is rotten.”

Still, I must be fair. If at that moment in May 2017, if you demanded that I call my Vol. 2 review “fresh” or “rotten,” I would have had to say “rotten.” Only under duress. Most of my review did focus on ways I felt the movie failed to meet its own goals, or contradicted its own themes. But Rotten Tomatoes didn’t ask me this question. Instead, someone else chose a quote from it. And they stuck a little “splat” icon beside the review, interpreting my creative work—itself an interpretation of James Gunn’s space-comedy film—as saying, “That movie is rotten.”

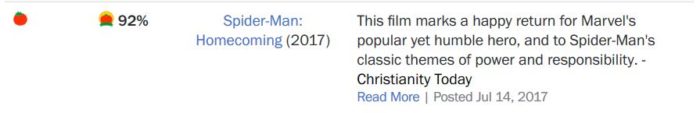

My second superhero movie review at CT, for Spider-Man: Homecoming, was more positive. Rotten Tomatoes showed this as a “fresh” review.3

But at this point I’d begun to challenge the whole idea of aggregate-review websites.

Especially because people—and often movie marketers themselves—have been citing Rotten Tomatoes rankings as authoritative. As if these rankings are some definitive, mathematical or legal verdict on whether “everyone knows” a movie is good or rotten.

2. How and why I set my Rotten Tomatoes trap

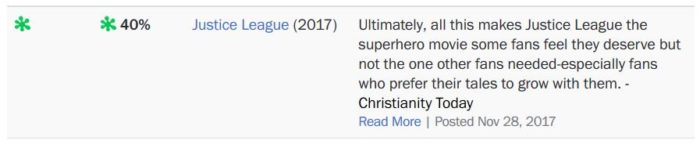

Months later, I reviewed the theatrical release of Justice League for CT. I didn’t go into this thinking, “I’m gonna set them a trap.” Instead I wanted to let my conflicted feelings about this movie—a fun but ultimately empty super-teamup-flick—spill into the review. I couldn’t help the fact that I knew a far more daring, lengthy, and epic film had been lost in the cutting-room. (#ReleaseTheSnyderCut!)

But what if you didn’t know that? What if you, say, just wanted a fun super-film with the Super-Friends for your kids?

Why then should I fill my review with subtle grousing about the Snyder Cut, and ignore the needs of viewers with different expectations?

In either case, this movie, Justice League, would only be “good” or “bad” depending entirely on what you expected about it.

In either case, this movie, Justice League, would only be “good” or “bad” depending entirely on what you expected about it.

So I wrote this into my CT review:

Justice League defies the binary “fresh” or “splat” Rotten Tomatoes ratings some viewers expect of movies. Superhero movies often succeed or fail based on the viewer’s personal preferences for hero tales and film genres: If you prefer a short and entertaining story with fun characters and overall suitability for children, Justice League mostly works. If you prefer a story of heroes struggling fiercely to act as light in a cynical world that does not comprehend it, you may need to adjust your expectations.

Then I realized this paragraph ended up making a sort of trap for Rotten Tomatoes. I had explicitly said, “Justice League defies the binary ‘fresh’ or ‘splat’ Rotten Tomatoes ratings.” So how did a staffer/editor/whoever-it-was at Rotten Tomatoes classify my review?

Well, they classified my review as rotten.

Which was literally and expressly contrary to what I’d said.

3. What lessons can Christian fantasy fans learn from this?

First, we must recall that movies, like any stories, are a highly subjective medium.

And as a hundred thinkpieces, taking positions in the matter of Scorsese v. Superhero Movies have reminded us: Our interpretation of the very concept of “cinema” depends on our expectations. If you expect some deep meditation on The Human Condition, you will get annoyed by the fantasy tale of a man, shot full of magic/science, who turns into a noble super-soldier. But if you, being a human, choose to pursue one real aspect of The Human Condition—the fact that humans are conditioned to love fantasy hero stories—you’ll likely love that kind of story.

From there, our interpretations of “good stories” are also subject to many different factors. These may include:

- Maturity. Do I want a lighter story-world that’s pre-“sanitized,” in a way? Or a darker world more closely resembling our own?

- Expectations. Am I tiring of genre conventions and want bold new stuff? Or am I happy with old tropes shown-and-told anew?

- Simple trends. Given that people may prefer whatever they enjoy to be popular, how does trend-chasing figure into story appeal?

- Life events. Given my personal circumstances at the moment, what kinds of stories will seem to meet me closer to where I am?

- Relationships. Am I more or less likely to enjoy a particular story based on whether my friends and family will like or dislike it?

- Time changes. Could a story I disliked decades ago seem brilliant after another few years, or even after a simple second viewing?

These items overlap, and they’re already too reductionistic. But the Rotten Tomatoes concept reduces these human factors further still.

Second, we must see that Rotten Tomatoes rankings don’t, and can’t, take these factors into account.

When you start with a movie, a mix of many creative voices, energies, expectations, audience appeals, risks, consumer appeals, and beyond …

Then go to a movie review, a mix of the critics’s life-experiences and belief biases as well as all those human factors I’ve tried to summarize …

And then reduce this review still further to simple up or down vote …

Then you end up with a gross oversimplification of how movies work and how movie reviews work—or ought to work.

We should not expect movies to appeal to everyone. But an “aggregate score” of movies implies otherwise.

Nor should we expect movie reviews to share a single conclusion: fresh or rotten. But a binary score implies otherwise.

And in my case, I specifically disclaimed the whole affair as politely as I could. They still interpreted my review as “rotten.”

Well, something is rotten in the state of Rotten Tomatoes, and it’s not the reviews.4

Third, we must consider how Rotten Tomatoes favors movies that play it safe and consumer-friendly.

For this next I must again rely on a chap called Stephen M. Colbert (fandom writer, not TV host). While exploring the responses to DC’s new superhero universe-inspired movie Joker, Colbert noted how Rotten Tomatoes favors mixed-positive movies, but down-votes movies that have wildly enthusiastic or severely critical reviews. He writes:

For this next I must again rely on a chap called Stephen M. Colbert (fandom writer, not TV host). While exploring the responses to DC’s new superhero universe-inspired movie Joker, Colbert noted how Rotten Tomatoes favors mixed-positive movies, but down-votes movies that have wildly enthusiastic or severely critical reviews. He writes:

The unfortunate impact is Rotten Tomatoes and other review aggregators regularly give major boosts to movies where reviewers generally lean in a more positive direction, but few people react negatively, by presenting them as having a higher score than movies that were genuinely reviewed better, yet elicited more negative responses.

At the end of the day, everyone has unique tastes, and that includes movie critics, so the notion of taking all those disparate opinions on a movie, distilling it down into a simple thumbs up/down, then aggregating that into an average approval rating and expecting it to be applicable to individual audience members seems very backward. As always, audiences are better off finding a particular reviewer or outlet they tend to agree with and trusting in their reviews, or even better, take a “risk” and go see a movie with an exciting premise, cool marketing, or an actor or director you like and form your own opinion.

Fourth, Christians need to discern Rotten Tomatoes “scores” like we discern anything else.

As some of my readers know, I have a love/tough-love relationship with the “Christian popular culture discernment” “industry.”

On one hand, I’m enthused that more Christians believe in engaging our culture’s favorite stories, to help us know and love our neighbors.

On the other hand, I think our efforts can be mediocre and subject to trend-chasing just like anyone else in the world. In our haste to affirm the good/true/beautiful, we not only miss the bad/lies/ugly, but we also miss the fact that plenty of these “high-scoring” stories and songs may not actually be that great. Sure, our neighbors may like them. But our neighbors also get distracted by shiny, popular, trendy things. Or we may end up ignoring what our actual neighbors like, and instead valuing what (we think) the critics like.

Either way, we buy into bad assumptions about How To Find Good Stories—assumptions that are often based on consumer whims, bad critical expectations, and plain ol’ vapid trends, just like anything else in popular culture.

Because that’s. What humans. Do.

Instead of buying these assumptions wholesale, we need to be choosier “consumers.” We don’t just need to discern stories. We must also discern the systems people have attempted to “measure” stories so they can apply some supposed universal story-judgment onto that story for all other people.

If we rely too much on such systems for movie measurement, we’re subjecting art to expectations that are, frankly, less than human.

These systems ignore the complexity of art, our relationships, our life-stories at that time, and our own expectations of stories.

And ultimately, these systems can substitute an idol of safe, predictable, binary verdicts—this story is bad! this story is good!—in place of plain, complex, human reality, which requires at least a third option between the fresh and rotten, an option that says:

This story could be good or bad, depending on who you are and what you expect.

This would mean you must know yourself and your own expectations.

Which means you must think about movies, rather than have any critic, or artificially aggregated pool of critics, do that thinking for you. Because art is complicated and humans are complicated. Art is not a program, and we are not computers.

So let’s stop treating movies as if we can reduce them to binary scores, averaged percentages, or anything less than human.

- In this piece I’ll refer specifically to Rotten Tomatoes. But anything here applies to any website that attempts to aggregate review “scores” for movies. For that matter, my conclusions also apply to anyone who tries to apply some binary computer-logic “rule”—allowing only 0s or 1s—to any genre of creative expression. ↩

- I also reviewed a Christian movie, Dallas Jenkins’s The Resurrection of Gavin Stone, which I mostly enjoyed. After that, the magazine reorganized. I’m not sure they’re writing many movie reviews now. ↩

- Oddly enough, I’ve since warmed a little to Guardians Vol. 2 and soured a little on Homecoming. Which itself brings up another flaw of the aggregate-review idea: it leaves out the dimension of time and changed perceptions. More on this further in the article. ↩

- Even the website’s name, “Rotten Tomatoes,” implies a negative slant and seems designed to (1) posture itself as authoritative, (2) presume any movie being aggregate-reviewed is presumed rotten until found not-rotten. When even the site itself applies binary rankings, why not call it “Fresh Tomatoes”? ↩

This is exactly why I appreciate Focus on the Family’s PluggedIn site. They simply tell you what good and bad content is in the film, give you a generalized review and let you make your own choice. Lorehaven has a similar style of reviewing novels that includes a “discern” section. Rating systems drive me crazy. They are far too subjective.

The only problem is that I’ve never been misled by a Rotten Tomatoes rating. What percentage of people LIKED a film is not subjective. It’s objective. That’s actually very helpful. Viewers just need to keep it in context, which is not hard given that they split the “critic” reviews from the “regular peasants like me” reviews.

That is interesting, though, how Rotten Tomatoes classified your reviews for you. Didn’t know that was how it works!

I see your clickbait title. And then I clicked it, so it has justified its existence in the world.

Rotten Tomatoes seems committed to their binary system of either thumbs up or thumbs down. You pointing that out is of benefit to Speculative Faith readers. So thank you. (Though you aren’t going to change them over to a more nuanced system.)

However, the quest for simple answers is a very common human thing. I have in fact taken umbrage to some of your responses to certain theological issues (such as a Christian writer’s level of responsibility to readers) as being too simplistic. Yet certain reactions to things I said revealed at least some people thought I was saying something simple, too, just in the opposite direction from what you said. (Sigh.)

A nuanced and complex understanding of things apparently is difficult!

As for Rotten Tomatoes favoring mixed positive reviews with low strong negative ratings versus reviews that produce both strong positives and strong negatives, I think there’s some merit to that approach. Since viewers come from a wide variety of backgrounds, a lack of any intensely negative reactions is a pretty fair indicator that the while general viewing audience may not love a particular film, at least they won’t be angered by it and feel cheated out of the price of admission. Polarizing movies that some people love and some hate can justifiably be considered worse in general than movies that almost everyone likes a little.

Though I think such a system, even if justifiable under the notion of a-film-most-likely-to-provide-fun-for-everyone, in some ways discouages risk-taking and supports mediocrity. Unfortunately the same vibe operates in books as well as movies–people tend to avoid negatives, more than seek positives. At least at times…

When perusing movie reviews, I frequently think back to the movie reviewer for the local (“major metropolitan”) newspaper for several years back in the day. His reviews were generally interesting and informative – but after a little while, I realized that his tastes were significantly different from mine; in fact, it was 100% reliable that if he panned a SF/F film, I would like it, and if he approved of an SF/F film, I’d hate it. That rule didn’t apply to other genres, but I kind of miss the usefulness of his reviews.

I kind of enjoy reading reviews sometimes. They’re kind of a good window into what people like and how they think, which can help authors learn to write better. That said, many of the reviews I’ve read were either for media I’ve already consumed, or media I was going to consume anyway. I’ve found myself disagreeing with a lot of reviews and have long since seen them as subjective. So if a show sounds really interesting to me, and I see a lot of negative reviews for it, I’ll probably still give it a shot anyway.

I practically never use Rotten Tomatoes, though. Most of the reviews I read are from blogs, Amazon, or maybe IMDb. And, a lot of times I just read them for fun, and as ‘homework’ to learn how to write better. Not in the sense that I automatically follow all the feedback people leave in reviews, but in the sense of ‘oh, here’s what tropes people get tired of and why. If I want that trope in my story, how can I present it in a way people actually like?’

One thing I learned from when it comes to subjectivity are the Star Wars prequels. I liked them, and when they first came out I didn’t even really hear much negativity surrounding them. So it surprised me when I started getting online and hearing such strong negativity toward them. Objectively, they didn’t seem worse than a lot of other shows that people loved or thought were ok. They added some interesting lore, and if you want to nitpick at them for things like dialogue, why not nitpick at the originals for having bad special effects or something? People can like whatever Star Wars movies they want, but at the very least I apparently have weird tastes and have to see for myself if I like something before completely writing it off.

You did not trap anyone. You basically said it won’t really please anyone. That is literally what you said out of the abundance of your Snyder fanboy heart. They saw through it. The fact that you thought it was Rotten was spelled out in everything except a caveat you didn’t truly believe. You truly need beta readers if you suppose that whinging Justice League review was as nuanced as you claim. The header literally notes your view that “It only kind of succeeds,” which is funny when you go down your list of almost entirely negative criticism of the film versus what you wanted it to be.

I’m sorry you hated that they didn’t make your Injustice League movie. I truly hope they release the Snyder Cut so you can finally be more honest about the theatrical version. For the record, the only DC movies I have enjoyed lately look nothing like BvS or Suicide Squad. They look like Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Shazam and… Justice League.

As a point of irony, this article could have been Fresh, showing how Rotten Tomatoes’ more selective critic rating system differs from audience reviews and could he used to explain some of the noted occasional disparity between the two assessments. Instead you stopped just short of that to give us a clickbait “trap” that only exists in a caveat that is wholly inconsistent with the rest of the review.

Until we reach The Last Door…

Tony, you also reveal a rather basic ignorance of article publication yourself, in presuming that a writer personally writes the subhead or title of an article; in fact, these are usually written by the editor, and this was the case here.)

The “clickbait” was tongue-in-cheek. And your line “you basically said it won’t really please anyone” is a gross misreading of my original review.

Rather than ask questions or even offer gracious pushback for the main thrust of the article—as several other readers have so easily done—you’ve instead returned to your obsession with yelling at other people’s fandom and are just acting again like a plain and dull middle-school bully. How come?

I don’t agree with you. I have valid reasons for my positions despite your mischaracterization of my objection as an “obsession” and as “yelling… like a plain and dull middle school bully.” I get it. You hate it when people don’t agree with you. Get over it.

Your editor undermined your article in favor of a provocative title. Big surprise. Your editor didn’t do you any favors here. It’s not tongue-in-cheek. It’s the very claim you’re claiming your “trap” proves.

I write my own article titles precisely because editors prefer clickbait. Editors aren’t marketers or even writers and they shouldn’t get to write headlines, like, at all.

I don’t owe you gracious pushback. Sunday school servants have turned plain spoken honesty into a sin, even when they applaud the Nazarene for His of times on-the-nose honesty. Stop tossing rocks out the windows of your stained-glass house if you don’t want them tossed back at you. You made a false claim that what you did constituted a trap. None of those gracious push backs were honest enough to tell you that with great plainness of speech. Your review wasn’t nuanced. It was negative with the caveat that you might like it if you like watered down fan service (which came across as snarky and snobbish, frankly).

But you’re welcome at any point you demonstrate why my summary of your fanboy review was a gross mischaracterization. If you’re done trying to bully me into silence that is…