Rearranging Icons 7: Coming Full-Circle

Back again for a last tussle with icons, my words in blue, Stephen’s in black.

———————–

Hi, Stephen!

Last week was a total bear…spent most of it in St. Louis, where my daughter’s high school robotics team was competing in the FIRST Robotics World Championships (details here). Thus this late reply and lack of commenting on the website. I’m going to keep the response part of this brief to leave room for summary comments on the series.

Yes, I think there’s a tendency, particularly in Christian fiction but not exclusive to it, for writers to become so caught up in the urgency of their message that they neglect the art of storytelling, and it is an art. Stories are meant to transport a reader or listener from their everyday life and immerse them for a while in something new and wonderful. We see the world through someone else’s eyes, or at another place and time. We might experience a world totally different from our own where things can happen that are impossible here. When that delicate bubble of immersion is lost through clumsy writing, or a sales pitch, or a product placement, or a reminder that there’s going to be a test on this material in a few minutes to make sure everyone’s been paying attention, the opportunity to communicate those things we care about can be lost forever.

Epic stories glorify our Author by showing the growth of characters into “icons.”

They can, but there aren’t many examples of characters, as compared to the total population, who actually manage this. And that’s okay. The community of characters we can rightly call icons in the truest sense of the word should be an elite group.

Okay, now you’re just yanking my chain. 🙂 Popularity only scratches the surface, and it’s usually transitory. An iconic character is timeless because they reflect an eternal longing within us. Out of the millions of characters conceived since we began telling stories, a few stand above the rest, and I think if we all sat down for an hour or so and composed our own short list of such characters, we’d agree more often than not.

By contrast, I’d been thinking about this first in the sense of a character trying to be like the ultimate Character/Icon, Christ (or a fantasy-world equivalent). Yet this is similar to a character who wants to be like an idealized icon in his story-world. Luke wants to be the best Jedi Knight. Peter Parker wants to be a great superhero. Aang wants to fulfill his mission as the Avatar, master of all four elements among the four nations. All of those are in a sense quests for “perfection.” They’re what drives the character’s actions.

And most of that is simply muddling through. The characters have only a glimmer of what it is they’re searching for and what it all means. We identify with them because we do the same kinds of things and make similar mistakes along the way in our lives. When the characters keep faith with their quests, and press on when everyone is telling them they don’t have a chance, they transcend their weaknesses and overcome their foes and obstacles. In witnessing their victories, we envision hope for an epiphany of our own, if we endure to the end.

The icon is a point of reference, a target, a bar set a few inches above our personal best.

Exactly. And it seems that in reality and stories, the threshold of “perfection” will always be higher than the person can ever reach. Christ is in His place and we’re in ours, unable to rise further because He was first and always. In reality, we should prefer it that way.

And yet, He calls to us, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” It’s compelling, and terrifying.

A character is trying to be an icon, an image of the Greater, but hasn’t yet arrived. This leads to a story’s plot. Heroes (and even villains) have not yet achieved their goals.

From the character’s point-of-view, I don’t see this happening very often. Characters are mostly trying to just live their life, or survive to see another sunrise. Their personal growth is something they don’t realize until near the end of their story, though that journey is visible to the reader and part of what keeps us engaged.

Dorothy’s trip to Oz becomes much more illuminating in retrospect when we realize it’s never been about making it back to Kansas–she could have gone home any time she wanted to. Her adventures help her understand that everything she’d ever wanted was right there with the friends and family she’d taken for granted. She’d been searching for a Wizard to solve her problems, but he had nothing to offer she didn’t already possess. The power of the story lies in the fact she spends most of it pursuing the wrong goal, yet through persevering on the journey, she gains a wisdom that is more valuable than anything she (or we, if we were encountering the story for the first time) expected.

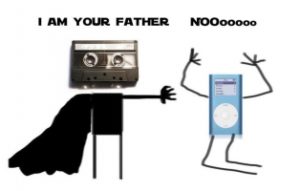

Likewise, to use some of your examples, Luke Skywalker’s quest takes on an entirely different meaning once he discovers his father’s true identity. Peter Parker learns that “with great power comes great responsibility,” and the lesson costs him dearly. Aang enters the Avatar State and finds the destination of his journey as much a threat to his soul as a solution.Thus, as I wrap up, a summary of one “formula” resulting from this series.

Likewise, to use some of your examples, Luke Skywalker’s quest takes on an entirely different meaning once he discovers his father’s true identity. Peter Parker learns that “with great power comes great responsibility,” and the lesson costs him dearly. Aang enters the Avatar State and finds the destination of his journey as much a threat to his soul as a solution.Thus, as I wrap up, a summary of one “formula” resulting from this series.

- God is the Axiom, the image of no one. He is Himself, the I AM.

- Jesus Christ, fully God and fully Man, the second Person of the Trinity, in His eternal existence as the God-Man, is the “icon” of God (Col. 1:15; Heb. 1:3).

- As redeemed saints, Christians are “icons” of Christ (Rom. 6:5, 1 John 3:2).

- Likewise, story characters are “icons” of us, in their complexities and choices.

Sigh. Yeah, maybe. These are true statements, but as a formulation, it gives me an image of characters designed like little Russian nesting dolls, and that doesn’t feel natural. In a way, it’s emblematic of this entire discussion. The harder we try to make this icon metaphor fit into the practical business of writing and understanding literature, the squishier and messier it becomes. We began with something that sounded like an Ideal Form in the Platonic sense and we’ve come back around to characters that resonate with us precisely because they resemble our fallible, vulnerable selves. We’ve covered the spectrum from characters that represent our most noble and exalted aspirations to characters that give us hope because they’re slogging through the mud of life right beside us. Very different conceptions of “icons,” but each true and important in their own way.

And for me, that’s the bottom line. Show me Christ, of course, but don’t forget He’s the Way, the Truth and the Life. Show me truth. Show me truth in action. Show me truth lived out in a real world filled with real people with real problems, even if it’s a thousand light-years away and runs on magic. Show me truth illustrated so vividly I can feel it to my very core. Don’t tell me what to believe and then figuratively stand off to one side waiting for me to come around to the merit of your argument. Instead, invite me to share a world that will leave me no choice but to believe, once I’ve experienced it.

This has been fun. We ought to do it again sometime, maybe with a topic a little less formidable.

Fred

That’s one thing I appreciate about these posts, and the general tone of discussion at Speculative Faith: a willingness to admit when all this talking really isn’t getting anywhere and we’re starting to get nonsense. I am in a writing class at a Christian college right now, and it doesn’t feel like we have enough acknowledgement of “okay, enough talking for now.” I get so fed up with the theories in that class..

Nonsense? You haven’t heard anything yet. Just wait until we deliver our Grand Unified Theory of Star Trek, Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

I recently wrote a blog post about this same thing.

http://netraptor.org/blog/2012/04/why-christian-spec-fic-writers-shouldnt-include-jesus/

My conclusion being that we shouldn’t try to include a Jesus figure at all, or even try to write about Christians. Just tell a good story. If there’s a redemption message, it should arise organically in the story. We shouldn’t strive to tell a sermon. It’s when readers come to us, the authors, enthused about our stories and wanting to meet us, that we have a chance to witness.

It sounds like everyone is agreeing that the discussion isn’t “going anywhere” and that it’s ended at about the right time. I also agree, yet I do wonder whether perhaps the goal has been misunderstood. What, after all, do we mean by “going anywhere”?

At the risk of sounding loosey-goosey postmodern, the conversation itself has, at least for me, helped to push my imagination in different directions. Because icons, or whatever you wish to call them, touch on so many life areas — religious, fictitious, and beyond — this is likely more relevant than even we know. And I doubt anyone’s intent was to “get anywhere,” e.g., master the topic. We’re dealing with profound mysteries here, about the nature of Christ the God-Man, how God’s image (the imago Dei) is reflected in even fallen people, and how “icons” remind us of Him, or ourselves.

Anyway, I agree with Fred that we should try this again, with a less-formidable topic!

Some thoughts for continuing conversation, and also to clarify:

And in fact, storytelling as art that starts as art in fact does better “preaching.” It fleshes out truth, putting skin on it, singing it if you will, rather than simply repeating it.

And for the Christian, God is glorified. We “get” more of His wonders in fiction, in a way that we could never experience by hearing another sermon, or by reading a sermon wrapped in the guise of fiction. God is glorified uniquely in fiction; sermons can’t match it. Citation: the Bible gives us not only Romans and 1 and 2 Kings, but Psalms.

Amen. Because the reader feels betrayed (or should feel betrayed!). The material becomes a smaller something to use, not an epic, imaginative something that uses you. The humility of experiencing this other-world is lost, exchanged for a kind of arrogance. This story isn’t really real, and I won’t be “taken in.” Instead I must “use” this for my own ulterior goals. Or: This is just to keep the kiddies entertained.

Definitely. I think that does seem a bit far-fetched. Kinkade’s paintings were simple, pretty little pieces, not emblematic of Perfect Christian Art, or iconic, or horribly subversive of Real Art. I’m with you in saying that when we get rid of those silly assumptions or reactions, we can enjoy what he gave the world, in perspective.

Again agreed. Any problems result in the abuse of this kind of art, not necessarily in the artist himself. From what I’ve heard, some Christians, though, have done the equivalent of chopping out all the Psalms that extol God’s Law or lament our sinful world, and only enjoyed the “happy” Psalms. God gives us many kinds of Psalms even in that one work of Spirit-inspired literature; that’s His “full body of work” in that collection.

Yep. And that’s why we can all make a little fun of exclusive focus on Gritty Reboots™ or “realistic” fiction. C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape “wisely” reminded us that “the real world” isn’t just horrible things, but beautiful things, and it is the devils, not the angels, who want to make us forget that the beautiful things are just as real as the horrors.

I’d love to explore this in future works — or rather, sit back and let you do it. The last thing I would want to do is condemn any craving for some kind of beauty as terribly unspiritual and legalistic. Ultimately, all our cravings for beauty have their limits and should be conformed better to the final and first Standard of Beauty, God Himself.

Somehow sparkling vampires leap to mind. …

I’m no populist, but I think I’m with you that while the masses are never all “wrong” or all “right” here. Popular art and literature gets popular for reasons that, under the abuses and sin-twistings of humans, are ultimately good. It just takes some work to cut through the per-versions of sin, to find an underlying, redeemable good desire.

Here’s the distinction I was making: it’s between a character who is an icon, naturally, by representing a human being or type of human being, and a character who has proved so timeless and endearing that he/she indeed becomes iconic. An icon of icons.

Frodo Baggins. Gandalf. Aslan. Superman. Harry Potter. Ebenezer Scrooge. More?

Okay, here’s a problem. Or maybe it’s not really a problem. I can’t think of any “evangelical” character who takes that role. This may be inevitable for two reasons:

Thank God He also equips us for that command, by clothing us in Christ’s righteousness and empowering us with His Spirit to “work out our own salvation with fear and trembling,” knowing that God is working in us (Phi. 2: 12-13).

Agreed. I think that’s because of some false notions of our own real-life character journeys. We don’t master, 100 percent, any particular sin, and then “level up” with experience points, never to fall into that sin again. We can get better, and then have a bad night’s sleep or a bad day and then, thanks to the old man of the flesh (Romans 6), down we go again. I’ve seen this represented by graphs that contrast the false view of Christian growth — a semi-straight line, sloping gradually up from left to right — with a more-accurate view — a jagged series of curves and dips, still gradually sloping up and generally getting better, but with plenty of huge and wide plunges along the way!

Good character growth will be much the same. Sir Rockcastle the Heroic may have conquered his fears in Book 1, and learned to communicate his feelings, and rescued the damsel and gotten married in Book 2. But if the author has any sense and knows his or her own struggles, Sir Rockcastle has not totally conquered all fear or other sins.

I like your Oz example, though I’ve never quite understood the appeal of The Wizard of Oz film itself (1939). Seems like an odd drug trip to me (along with humanistic philosophy, if you overthink it). I suppose one would have had to grow up with it!

The misdirected quest, or original quest that is superseded by a greater need — another potential topic for another series.

Agreed. Like characters themselves, striving to become accurate “icons” and much more so “iconic” like that short list of famous heroes, we can only approach this invisible, asymptote-like line of wrapping our rhetoric and imaginations around this.

As I said in response to this, in my earlier email to you:

(Joins in on the chorus) Don’t just repeat the Gospel or seek to explain it, a la the book of Romans. I’ll do that when I read Romans or hear or read a sermon about it. Give us stories and literature like the book of Psalms, that make us feel and experience these truths vicariously. Is this “useful” when we’re in similar real-life situations? Maybe. But is this useful mainly to reflect to us more of the ultimate Icon Himself, Christ? Oh yes.

Recently I heard a nonfiction-oriented guy, pastor J.D. Greear, say this in a way I haven’t heard before. We make such a case here not just because this is more effective, or because it’s more logical, or even because it’s How a Story Should Be and it’s artful. Instead, it’s a downright Biblical case to make, based on how God reveals Himself.

Oh, this is definitely an example of how the journey is often more important than the destination. We envisioned this as a couple of guys having a conversation, as if we’d spent a pleasant afternoon shooting the breeze at a local coffee shop. I think some good stuff emerged along the way, though it makes for odd reading in this venue. We usually write very focused articles with a “point.”

I liked it. I still think we need to do “Stephen and Becky Talk Tolkien.” 🙂

Or they do the opposite, excising just about everything but the Great Commission, the Romans Road, and the book of Revelation. I think you’re getting into that with your post today on the merit of stories.

I don’t think it’s a problem, more of a symptom. Christian literature, as a genre, and Christian spec-fic even more so, is still maturing. The fresh voices, new approaches, and stronger characters will emerge in time, if we can escape the trap of chasing success–trying to write the next Lord of the Rings or a Christianized version of the current secular fad. We need to start setting trends versus following them.

It helps to live in Kansas. The movie’s obviously a caricature of Baum’s story, but I always thought it was cool that, despite all the Technicolor wonders of Oz, what Dorothy really wants is to be reunited with her family on her drab, monochrome, Midwestern farm.

————–

This is one reason I think there should be more Biblical fictions–to remind us that there are PEOPLE in the Bible stories, people with headaches and faith and odd things like that. Because otherwises, we just see them as flannelgraphs and cartoons.

Well said. It’s also why I think, one, we shouldn’t distinguish between historical and Biblical fiction (that is, it’s more accurate to use Biblical as as subgenre of historical in the way Civil War – era historical fiction is), and, two, not treat the Bible the same way we do a piece of fiction.