As our e-mail conversation about icons continued, we moved into more of a give-and-take format, so you’ll see lots of quoting and commenting on things we posted last week. In a couple of places, I’ve added some material for clarity and to round out my observations. Again, my comments here are in blue, but I’ll leave Stephen’s in black this time for easier reading.

I might suggest calling this series “Rearranging Icons,” which definitely gives a visual aspect!

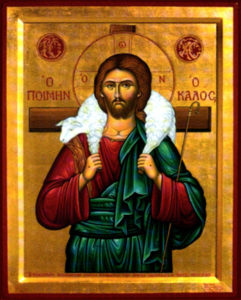

I think that works for a title. I know Eastern Orthodox folks usually have an icon corner or wall in their house, with icons of Jesus given pride of place at the center.

First, I like your working definition of icon, which I’ll adapt a little, here:

An icon can be a picture, symbol, archetype, stereotype, a graphic container or shorthand for something else. In the Christian tradition, an icon can be a specific kind of devotional image.

Works for me.

That leads me to consider some examples of icons:

Picture and/or graphic container for something else. The icons on my computer desktop.

I love computer icons as an example, because they’re an elegant way to represent a huge amount of information or a very complex entity and make it accessible at a touch.

Symbol. The sign of the bat from Batman…

Accomplishing the same sort of thing as a computer icon, but in a more conceptual way, without the touch or click. Most of the major superheroes have a designated symbol and color scheme that’s distinctively theirs. We see the bat, or Superman’s “S” symbol, or the Flash’s lightning bolt, etc, etc, and we’ve tapped into an idea that transcends language.

Archetype. These are especially common in stories. They’re the opposite of stereotype, and carry the connotation of a positive, an ideal…

These are the big ones, that we find in every culture from the dawn of time, and they speak to the universal aspirations and longings of mankind.

Stereotype. This is where it gets fuzzy, because the above-mentioned Damsel in Distress could also be an archetype. A stereotype may be a negative archetype, like the “shooting up heroine.”

Yes, we begin here to roll-in the impact of how we employ these images. I agree that stereotypes are almost always negative and often the basis for prejudice and discrimination. They can be useful in satire or cartoons, and can serve as a starting point for building a more complex character over the course of a story. We meet the stereotypical secretary in an office, typing memos and serving coffee, then discover she’s a whole lot more as her character develops and interacts with other characters. If we leave her mired in her stereotype, though, we’ve reinforced the negative aspect of that shorthand image.

Specific devotional image. Most people think of “icons” as a Catholic or Eastern Orthodox thing, but really I think Protestants have just as many icons, if not more. I’m thinking about the Cross on a wall or necklace. Or an outline of clasped hands. Or maybe even the old(?) “WWJD?” bracelets.

Perhaps the ultimate "power tie."

Yes, and I think most people never realize this. We Protestants have scrubbed our religious culture of obvious icons, but have become tone-deaf to the meaning and power of the iconic images we’ve gathered to fill that void, many of which send incoherent messages or clash with one another because they’ve been adopted without much thought. I’ve seen some references to the plasma screen as a modern Protestant icon. Where you do find art displayed in Protestant churches, it’s often a grab-bag of popular images like the “praying hands” you mentioned, or Richard Hook’s Jesus pictures, or the bearded gentleman praying at a table set with a cup and a loaf of bread, or more recently, Thomas Kinkade’s work. Our pastors may not wear vestments, but they have their dark suits and power ties (or chinos and polo shirts). We’ve got lecterns, and banners, and, still, some stained glass windows.

The Bible itself is often employed as a physical icon, open on the altar or Communion table, and that image carries a ton of unspoken meaning for any Christian. Of course, it’s also an icon of Jesus Christ, the Living Word. Like the computer icon, it contains a huge amount of information in a very compact package, accessible at a touch.

Like you said before, because we’re not talking about computer graphical-user interfaces, superhero crime-fighting psychology, or even devotional images, we’ll likely want to focus tighter here on the “icons” that relate to fiction and literature. Still, I think the others are more related than we think, or else, should be — such as the symbols, or devotional images. “Embedding” an icon in a work of fiction could strengthen its classic value, or even (to borrow from another Christopher Nolan film) commit “inception” in the subconscious mind of a reader. You don’t think you noticed the symbol or icon there, but your brain did. And sometimes those archetypes are so deep that it takes years to find them…

I agree, and I think this is a central issue of this series, the fact that when we tap into the strongest, most universal icons in our fiction, we create a powerful resonance in the mind of the reader. Very little “telling” is necessary. You see the image in your mind, and you know. “There’s truth here, and somewhere deep within me, I recognize it.” The truer the archetype, I think, the stronger the reaction, which leads directly to your point about Jesus as the ultimate icon.

I could get into all kinds of distractions given the relation of mythology and archetypes to Christianity and Christian fiction. So let me instead briefly address the issue you raised, about icons in Church history. You mentioned the icon controversy that was addressed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council in Nicea, in 787 A.D…

The Council surveyed the underlying theology issues — about whether the material universe was good or bad, and how Christ’s incarnation with a human body and face and therefore an “image” Himself affected the controversy. Ultimately the Council ruled in favor of the Iconodules, I’ve read, and said that churches could keep the icons, right alongside symbols of the Cross, and the Bible itself. Here’s a quote I found:

“I do not worship matter, but the Creator of matter, who for my sake became material and deigned to dwell in matter, who through matter effected my salvation.”

— St. John of Damascus

St. John of Damascus’ entire treatise on holy images is available at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/damascus/icons.html. I believe he wrote this while living under Muslim rule, which must have been scary, as Muslims of his day (and still today, I think) were dedicated iconoclasts. Muslim ideas about God and worship were beginning to filter into the wider global culture, and they fueled some of the controversies the Church Councils were dealing with.

For anybody wanting an outline of the Councils and their impact, which continues today, Michael Hyatt (President and CEO of Thomas Nelson Publishing) has provided a great seminar series in podcast, starting at http://ancientfaith.com/podcasts/eastwest/the_ecumenical_councils_-_part_1. The podcasts are accompanied by transcripts if you’d rather just read, but they’re a good listen.

One could replace the word “matter” up there with anything else: the church, God’s Word, even stories. In fact, I was recently amused to see a Catholic activist, posting on a Protestant ministry’s page, who accused Christians of worshiping Scripture. For “proof,” he presented a theologian’s quote that praised the Bible’s value to society and Christians. My reply: “This is just plain ol’ silly. Or maybe it’s playground revenge for evangelicals who say Catholics ‘worship saints’ or ‘worship Mary.’ …

A great example of people throwing stereotypes back and forth at each other, and how unproductive that is.

But this does reveal something important: that any icon can be used for good or evil. If we throw out the Gnostic/Pelagian notions that it is our corrupted world, and not our evil hearts, that result in sin, then we are also forced to throw out objections to all icons — even icons in worship. Icon critics err in assuming that any visual representation will result in idolatry. They also are found inconsistent. A modern example may be a Christian who opposes everything about the Catholic Church, but prizes a certain older Bible translation as the only one that any Christian worth anything should value and adore. That’s iconization at least as bad as those in another denomination who start confusing that picture of Jesus with the real Jesus.

And most folks from a tradition that includes icons will recoil at the idea of worshipping the icon itself, but also likely acknowledge that some people veer into malpractice and do that. As per our discussion earlier regarding Protestant icons, throwing out the icons for fear of abuse eliminates neither the icons, nor the abuse.

Likewise, avoiding symbols, archetypes, and sometimes even stereotypes in fiction will not prevent their abuse, but may have a worse consequence: the proliferation of poorly-thought-out substitutes. It also discards an opportunity to tap into powerful images able to communicate profound ideas at both the conscious and subconscious levels.

The Rocketeer continues this tradition.

One illustration I find useful is the scene you’ll find in most WW II movies focusing on the fighter or bomber pilots–The pilot settles into the cockpit, and we see he’s taped a photo of his wife or sweetheart to the instrument panel. He kisses his fingers, touches the photo, and then cranks the engine and takes off. Always makes my eyes water a bit. He’s not in love with the photo, he’s in love with the woman the photo represents, and he’s making a powerful spiritual and physical contact with that woman via the photo. It’s a window that opens onto reality. The photograph brings to mind a host of memories and emotions that encompass the truth and totality of his relationship with a very real person.

Thus, if I start worshiping on icon, I may need to get rid of the icon, but it’s not the icon’s fault. It’s mine. I have confused the means for the ends. And this would be true for any good gift of God that we abuse.

Yep. It’s the distinction between employing something as an aid to worship versus adoring it as an object of worship. And I think it’s important to note, as John of Damascus did, that honor and reverence are not the same thing as adoration. I might have a personal altar where I place a Bible, and a cross, and a picture of Jesus, and I could use those objects to help me focus my worship and remind me in a physical, tangible way of who Jesus is and everything He’s done for me. While I would quite rightly treat them with respect for who and what they represent, it would be a much different thing to take any of those objects and say of them, as the Israelites did of the golden calf, “This is the God who brought me out of captivity into the Promised Land.”

Speaking of the real Jesus, I believe this discussion will keep returning to that, especially given this time of year. It occurs to me that He, and only He, matches all the aspects of your helpful definition of icon, and I’m sure I can find Scripture that proves every one of those. Christ is the ideal, the “exact image” of God the Father. And yet He is also a Man, a real, flesh-and-blood Man. He’s the only perfect unity of each. So if we think of an “icon” as spiritual and more-abstract, and a “character” as physical and tangible, He is both.

Exactly, though I might suggest that the difference between a “character” and an “icon,” in the literary sense, is more an issue of scope than physicality. A character seems to me to be more of a specific case that may incorporate elements of an icon, or several icons. It conveys truth, but not its fullness. If Jesus is an icon, we, his servants and disciples, are characters that in turn reflect His perfect image, as yet imperfectly.

I’m looking forward to our next exchange, and very glad for the opportunity. And though I’ve likely gone on long here, and may edit this when I post it in response to your piece, I hope it covered everything well!

I’m enjoying this too. We may want to take another look at your outline and see if there are any issues there we need to discuss in more detail as we get closer to kicking this off on SF.

Fred

I think over the course of this conversation, the terms icon, symbol, stereotype and archetype have been juggled to such a degree that they’ve become interchangeable. I understand the need for brevity, and such shorthand can certainly accomplish this, but the conversation begins to fall apart when different words are treated as total synonyms. An icon is a sign or representation that points to an object by resemblance or analogy to it. The file folder on my computer is represented by an icon of a file. Icons of Mary look like the popular portrayal of Mary. Batman’s icon is a bat. When we say something is iconic, we’re talking about something that embodies a larger group by managing to represent and resemble that larger group. Darth Vader’s helmet is an iconic image for the evil Empire because he is both a product of it and a producer of it.

Archetypes and stereotypes are not only positive and negative sides of the same coin, they’re also true and false sides of that coin. An archetype is someone who rightfully embodies the most identifiable characteristics of a larger group. Superman is the archetype of crime-fighters, not because all crime-fighters can fly and wear a cape, but because he is the fullest realization of fighting crime. Stereotypes, on the other hand, are less about negative qualities, but about the unfair representation of a group by a single member or smaller segment of that group. In this case, you’re talking about broad, untrue generalizations: young people are all lazy, Christians are all judgmental, superheroes wear spandex. It’s the difference between Uncle Sam being an archetype of an American, and George W. Bush being a stereotype of all Americans.

“We Protestants have scrubbed our religious culture of obvious icons, but have become tone-deaf to the meaning and power of the iconic images we’ve gathered to fill that void, many of which send incoherent messages or clash with one another because they’ve been adopted without much thought.”

This, I think, is the problem. Not only have we scrubbed our culture from icons, but symbolism as a whole. A long while back, I read a blog entry that blamed Marburg for the lack of imagination in Christianity. The idea of transubstantiation, namely that Jesus can be our Lord’s Supper, and not just in it, or represented by it, broke down the Christians ability to reckon something greater than something they can hold in their hand. To early Catholics, there was this trans-existential tie between communion and Christ. Protestant fundamentalism has determined (perhaps because of our insistence on hyper-literal biblical interpretation) that everything must be taken at face value, with a one-to-one ratio.

I was recently amused to see a Catholic activist, posting on a Protestant ministry’s page, who accused Christians of worshiping Scripture.

I’m not sure that’s entirely unfair. Sometimes it seems that Christians try to use the bible as a contract, holding God to what he can and cannot do. Many make a case for or against some doctrine or promise of God, ignoring the context or meaning of the verse, in favor of what a particular translation or interpretation state.

If we throw out the Gnostic/Pelagian notions that it is our corrupted world, and not our evil hearts, that result in sin…

Again, shorthand is fine if you’re trying to achieve brevity, but only Gnosticism applies here. Pelagianism would say that worshiping an icon is the result of a sinful choice, not a sinful world.

While I would quite rightly treat them with respect for who and what they represent, it would be a much different thing to take any of those objects and say of them, as the Israelites did of the golden calf, “This is the God who brought me out of captivity into the Promised Land.”

And here’s where the problem lies, not in icons, but in idols. The calf was an idol that shared the name of God, but pointed to itself, rather than to Jehovah. Icons should point outward or upward. Idols point only to themselves. When we begin to treat an icon as an idol, we have our problem.

You’re right, Jeremy. And as hard as we try to maintain a distinction among these terms, we still manage to muddle them. This is a messy conversation, and that’s part of the reason we decided to just tack it up here as a conversation rather than a series of essays, lest we give the impression that we’ve got this all figured out.

Right again. The last thing we want is for this to devolve into “icons good” vs. “icons bad.” It’s more like, “icons are,” and the larger question is how we take that knowledge and use it to communicate better when writing and understand better when reading or watching.

This is a messy conversation, and that’s part of the reason we decided to just tack it up here as a conversation rather than a series of essays, lest we give the impression that we’ve got this all figured out.

I understand and respect that. Consider this my contribution to the conversation. 🙂

…the larger question is how we take that knowledge and use it to communicate better when writing…

Absolutely. And just as a veterinarian learns to treat dogs and cats separately, or even different breeds of dogs separately, and not lump them all in as fuzzy four-legged thingies, we must differentiate between all these different types of representations, or else we may mistake an successfully portrayed archetype for a stereotype. We might accidentally interpret an homage as an icon.

And thanks for the contribution. This conversation is meant to be public and open-ended, so jump in whenever you feel the urge.

I like how this ties in with what Madeline L’Engle says about icons in Walking on Water. The icon is an idealization, not an actual. And the picture of the pilot in WWII actually helps clarify it a lot.