Realism And Twenty-first Century Storytelling

As I mentioned last week, I’ve been watching the five different Star Trek shows on H&I. I hadn’t remembered the storytelling in each being particularly different from one another—except for the original which felt quite artificial at times. I mean, the women wore those ridiculous miniskirts and nearly every episode had the crew shaken and falling. Not to mention that the poor red shirts were doomed to destruction and that Captain Kirk, in all likelihood, would win some female’s heart before the end of each episode.

As I mentioned last week, I’ve been watching the five different Star Trek shows on H&I. I hadn’t remembered the storytelling in each being particularly different from one another—except for the original which felt quite artificial at times. I mean, the women wore those ridiculous miniskirts and nearly every episode had the crew shaken and falling. Not to mention that the poor red shirts were doomed to destruction and that Captain Kirk, in all likelihood, would win some female’s heart before the end of each episode.

What I’ve found by watching the shows night after night is that the storytelling mirrors the storytelling of movies. Some of the earlier shows actually seem a little slow. There’s more dialogue and not as many things blowing up, not as many people falling to phaser blasts. But in the last show, Enterprise, the storyline is less thoughtful and more violent. More action packed, too.

Storytelling has changed.

We often talk about the need for realism in fiction, particularly in Christian fiction, but when we cite the movies we love, there’s little that is true to reality beyond the externals.

Of course, the externals are important. Who would want to replace the computer enhanced Aslan for an actor dressed in a lion costume? We want our Aslan to appear on the screen as real.

The desire and push for realism in our stories has given impetus to those who believe Christian fiction should include sex, profanity, and vulgarity. After all, those are real.

But where is spiritual reality?

I think there’s something else not particularly real in twenty-first century stories, no matter how real the computer generated characters might appear. We could chalk this up to “that’s just movies” if it weren’t for the fact that screen writing is beginning to dominate the way we write novels, too.

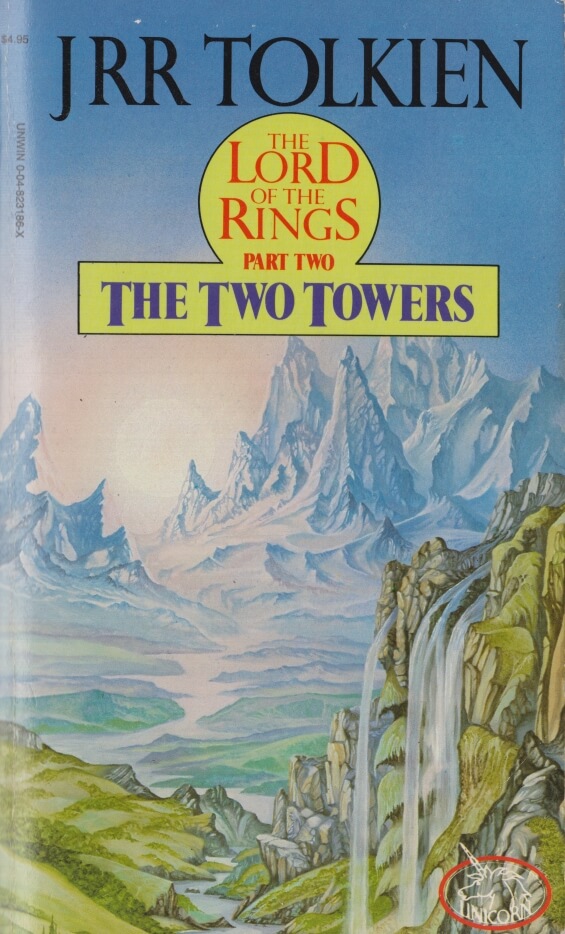

I’ll characterize this unrealistic phenomenon as too much conflict. The Lord Of The Rings illustrates the point.

Some time ago I watched the last part of Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers on TV shortly after re-reading the Lord Of The Rings trilogy. The main thing I noticed was conflict in the movie where none existed in the book.

Some time ago I watched the last part of Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers on TV shortly after re-reading the Lord Of The Rings trilogy. The main thing I noticed was conflict in the movie where none existed in the book.

For example, in Tolkien’s original once Gandalf had freed Theodin, the king of Rohan, from the influence of Wormtongue, he quickly became his adviser. Théoden did what Gandalf told him to do: trusted Éomer as his new right hand, sent the women and children away to a place of protection (not Helms Deep), prepared his army to march on Isengard, sent out word to gather troops to support Gondor against Mordor. In the film version, however, Théoden fought Gandalf at every turn. He was nearly as depressed and suicidal as Denethor the Gondor steward.

There was also enhanced conflict between Arwen and her father Elrond about her staying in Middle Earth for Aragon. She finally decided to leave–an incident that did not happen in the book.

Another “it did not happen in the book” example also involved Aragon. On the way to Helms Deep (rather than to Isengard, as the book had it), the people of Rohan were attacked by Uruk-hai and Wargs. In the battle, Aragon was dragged over a cliff and fell to the river. His companions presumed him to be dead.

Another “it did not happen in the book” example also involved Aragon. On the way to Helms Deep (rather than to Isengard, as the book had it), the people of Rohan were attacked by Uruk-hai and Wargs. In the battle, Aragon was dragged over a cliff and fell to the river. His companions presumed him to be dead.

Then, too, Treebeard and the Ents decided they would not help in the war against Saruman. Merry and Pipin tried to talk him into it, but he refused, only promising to take them out of the forest at whatever point they wished. On the way, they came to a place where Saruman’s forces had destroyed the trees, and the Ents then arose and fought. The motivation in the book is the same, but the conflict between the hobbits and the Ents never existed.

In the segments concerning Frodo, there were more of these manufactured conflicts. Frodo and Sam argued about the effect the ring had and about their disparate treatment of Gollum. Then too, Faramir insisted on taking Sam, Frodo, and Gollum to Gondor with the intent to use the ring (which they spoke of openly in front of all Faramir’s men) in the battle against Mordor. When they reached Osgiliath, they were attacked by one of the Nazgul. Under the influence of its presence, Frodo acted as if he’d been possessed and nearly put on the ring. Faithful Sam tackled him to stop him and they wrestled, with Frodo pulling his sword on Sam. None of this happened in the book.

As I thought about these differences, it seems to me that the movie was faithfully following the dictates of writing instructors who tell writers to make life hard for their characters and when it’s as bad as it can get, make it worse.

But is that reality?

Do friends always turn against one another? Does the hero always fall to his apparent death? Do the once mighty always succumb to discouragement and despair? Does doubt and fear always push loved ones to leave?

The answer is, no.

Tolkien got it right in his version of The Lord of the Rings—he told a realistic story. Borimir succumbed to the power of the ring, but Faramir did not. Denethor became suicidal, but Théoden did not. Gandalf fell to his apparent death, but Aragon did not.

In showing the strength of Faramir, the healing of Théoden, the prowess of Aragon, Tolkien enhanced Borimir’s failure, Denethor’s selfish choice, and Gandalf’s sacrifice. In other words, by not taking every character to the brink before leading them back, he magnified each case in which a character was taken to the brink.

In showing the strength of Faramir, the healing of Théoden, the prowess of Aragon, Tolkien enhanced Borimir’s failure, Denethor’s selfish choice, and Gandalf’s sacrifice. In other words, by not taking every character to the brink before leading them back, he magnified each case in which a character was taken to the brink.

If all characters are victims of disaster, I suggest readers or viewers stop caring and start looking for the “out.” Will the character die and come back? Have a narrow escape? Have a death that only looks like death? In truth, all the arguing and betrayal and refusal becomes—predictable and boring and unrealistic. Soon the characters seem more like caricatures because none acts with nobility or courage or hope. All display their flawed selves with so little inner struggle. And this, we’ve come to believe, is realistic.

Perhaps this twenty-first century version of realism is another way in which we are not addressing spiritual issues realistically. We are, after all, made in God’s image. We have within us a moral sense of right and wrong. We also have a sin nature. In essence, we are divided at our core.

We experience the truth of Romans 7 day in and day out, doing the thing we hate and neglecting the thing we know we should do. We struggle in the inner person. But Romans 8 follows, too. We revel in the freedom from the law of sin and death, we experience God’s sovereign purpose to work all things for our good, we enjoy His nothing-can-separate-us love. In short, reality is a mixed bag along the journey. It’s not all bad until the miraculously impossible reversal.

In story writing, I believe in conflict, I really do, though I believe in tension more. I wonder if twenty-first century authors aren’t needlessly creating artificial, big-bang conflict when inner-struggle tension, more true to life, actually would make for a better story. Tolkien’s work convinces me that more external conflict isn’t particularly realistic nor is it always the best.

The greater part of this post is an edited version of one that first appeared here in January 2013.

Yes! This is my biggest problem with those movies, and with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child — everyone is way too emo. There’s no light and joy. Everyone is dour and depressed and exhausted and burnt out.

–As I thought about these differences, it seems to me that the movie was faithfully following the dictates of writing instructors who tell writers to make life hard for their characters and when it’s as bad as it can get, make it worse.

I remember being at a writer’s conference and the leader of the seminar I attended pretty much saying that, taking a scenario from the book she’d read and creating ways to add difficulties to the. While I would have agreed that the scene she read was sappy and implausible–would a woman who’d just been told that the stranger who just presented herself to her was her long-lost child really buy into that and go right into the hugging and the crying?–the ideas for making things difficult didn’t seem to be much better.

There can be realistic conflicts–the woman denies, even forcefully, that she’d ever had a child, for example–and those conflicts would come out of the overall story.

But I can think of one possible exception. I say possible, because I haven’t watched this movie, but from what I’ve seen about it, “Grave of the Fireflies” is a movie about a bad situation that worsens and worsens and ends in tragedy.

https://www.amazon.com/Grave-Fireflies-Isao-Takahata/dp/B006LLY8LY/ref=sr_1_1?s=movies-tv&ie=UTF8&qid=1474346261&sr=1-1&keywords=grave+of+the+fireflies

Maybe the advice I heard a jazz instructor give can also be kinda-sorta applicable to writing, too, “There are no wrong notes, just wrong resolutions”. Arbitrary conflicts don’t work well, because they don’t have good resolutions. The made-up conflicts in the LOTR movies stumble because they can’t be resolved as well as the conflicts in the original stories.

What you mention is one of the main reasons I rarely watch movies any more. As my focus has become the reading and writing of redemptive fiction, I am more concerned than ever about the reality of the characters—the spiritual reality. Our relationships with the Lord are deeply personal. It should be that way with our characters also.

The results of our lives are largely unknown at the time, and fruit is our character—how much are we like Jesus. Somehow we need to be able to show the rhema of the Spirit—those words He gives us targeted at the specific problem and at the exact place where we are in our growth. That’s what the Sword of the Spirit is: rhema, not Logos. It’s not about quoting scripture at the top of our voices (though that does happen upon occasion). The Lord knows enough to talk with us in the vernacular. He does that to me all the time—cracks me up, He does.

What we need is spiritual realism. There’s enough drama there for almost any storytelling situation.

Every time I see your photo, brother, I am convinced you are my former editor from back in Versailles, Kentucky. I mean the resemblance is absolutely identical. Not sure if this Means anything or counts as a personalized revelation from the Lord to me or not!